My Art Mentors, Collaborators & Artistic Inspirations

Aesthetic Arrest

Iona Miller, 2010 Retrospective

From Smelly Art to Hyperdimensional Art

From Smelly Art to Hyperdimensional Art

Artful MENTORING: Where are you in the process of realizing your art, of becoming a Master of Art? Mentor relationships foster creativity. Master Mentors understand that every student has an art inside him or her, and has a Master who is meant to come out. The term Master comes from the model of apprenticeship, leadership education and from the Renaissance. Masters strive to learn how to recognize those elements in the world that emanate beauty, have symmetry and synergy. They are trained to feel and act authentically. They strive to find strength through balance. A Master is more than well-trained and much more than an expert. A Master has both a broad and deep understanding of his Art, recognizing patterns in history, in humanity, and connections between people throughout time and various cultures. A Master understands how his Art connects to the world as a whole. By mastering one Art, a Master becomes a Master in life in general.

There is a Master and an Art Inside Everyone - Michelangelo wrote, “Beauteous art, brought with us from heaven, will conquer nature; so divine a power belongs to him who strives with every nerve. If I was made for art, from childhood given a prey for burning beauty to devour, I blame the mistress I was born to serve.” All of us bring an art from heaven. Each of us has a specific vocation or mission in life -- to fulfill or realize our unique potential. The aspirant is a receptacle that needs to be filled. Master Mentors understand that every student has an art inside him or her, and has a Master who is meant to come out. They understand that they are not really the teacher. The Master within the student is the true teacher. They see their role as bringing the art or the Master to the surface.

There is a Master and an Art Inside Everyone - Michelangelo wrote, “Beauteous art, brought with us from heaven, will conquer nature; so divine a power belongs to him who strives with every nerve. If I was made for art, from childhood given a prey for burning beauty to devour, I blame the mistress I was born to serve.” All of us bring an art from heaven. Each of us has a specific vocation or mission in life -- to fulfill or realize our unique potential. The aspirant is a receptacle that needs to be filled. Master Mentors understand that every student has an art inside him or her, and has a Master who is meant to come out. They understand that they are not really the teacher. The Master within the student is the true teacher. They see their role as bringing the art or the Master to the surface.

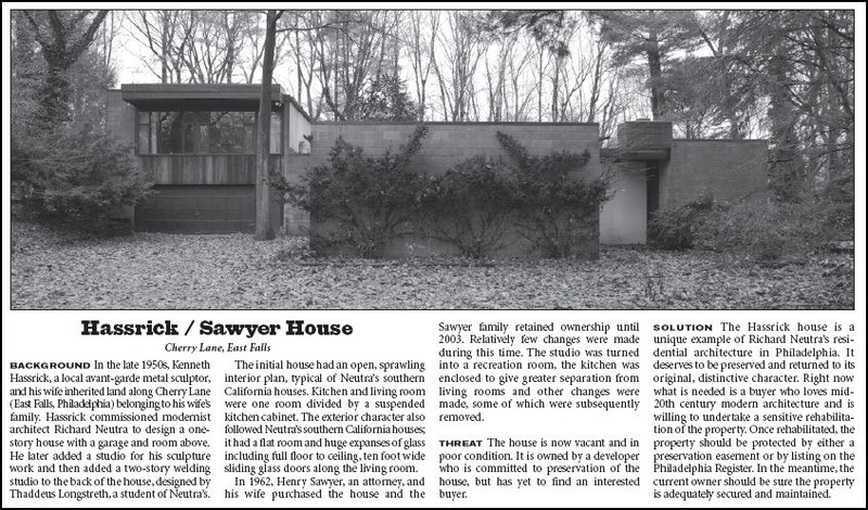

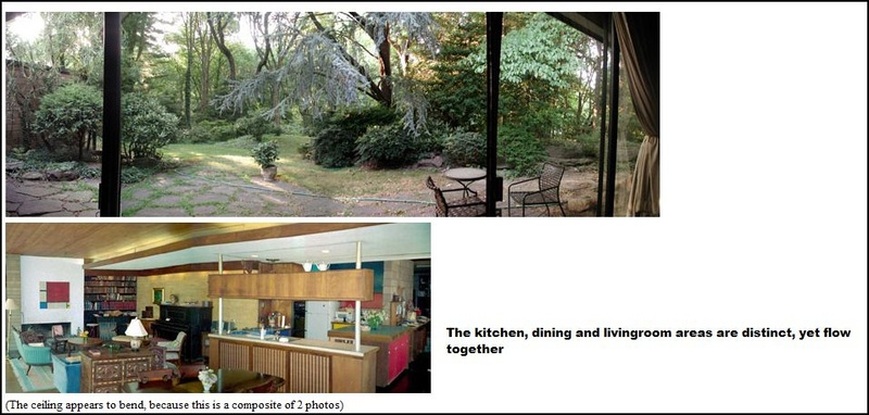

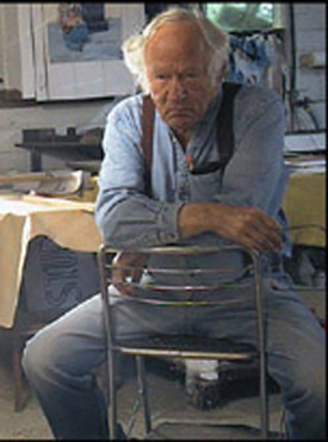

Ken Hassrick - Avant-Garde Sculptor & Painter - "The Body Electric"

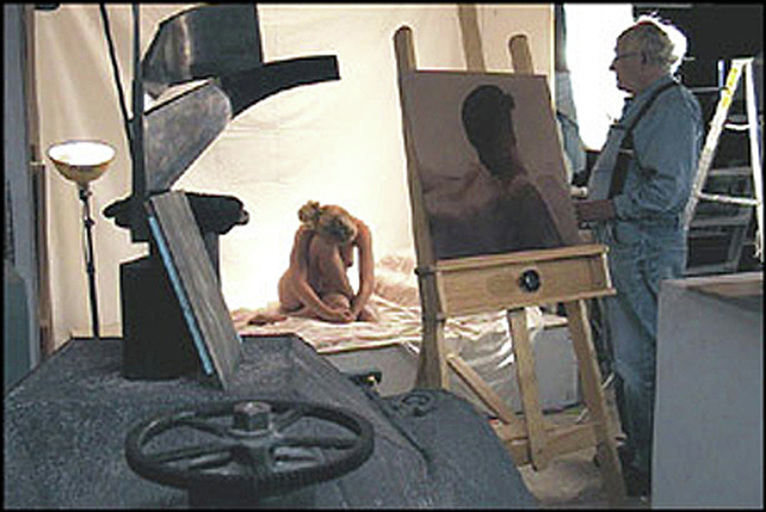

Prominent painter and sculptor Ken Hassrick has created works in abstract metal sculpture, wax, clay and plaster, most recently with a focus on evocative semi-abstract paintings of the female form. The female body has long been one of the classic subjects for artists and is without a doubt one of the most complicated and ever variable. Hassrick’s drawings and paintings reveal the classic subject of the female body, with its never-ending variations of form and interpretation. Whidbey painter, Ken Hassrick (1921-2004) spent more than 30 years exploring this evocative subject. "The Body Electric" showcased some of Hassrick's noted figurative compositions, ranging from realism to abstract. The artist, who died in 2004, spent more than 30 years exploring this evocative subject.

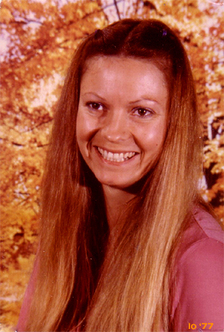

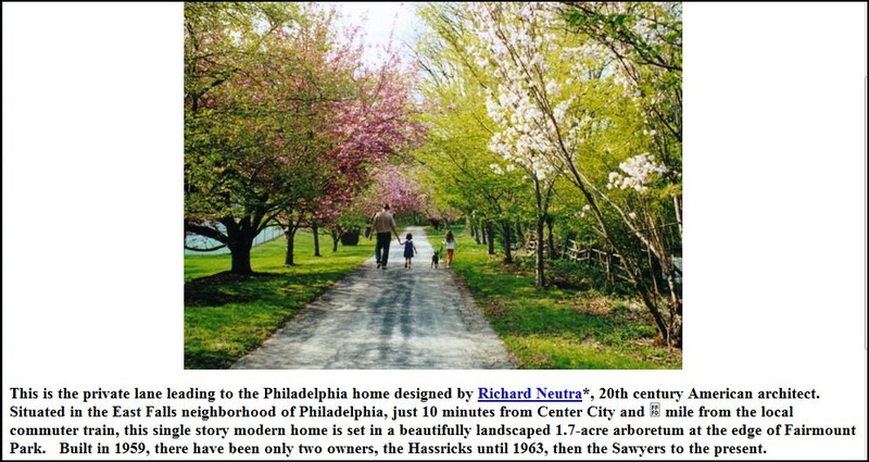

While I was his model, Ken Hassrick taught me about art and what it means to be an artist. Because they were Ken & Barbara, his wife was called 'Doll', instead of Barbi. Ken always had the best studio in the area in which he lived. The Hassrick's were originally from Philadelphia, Boulder, Co. and West LA before coming to So. Oregon to raise Morgan horses for show. Though he is known for abstract scuptures, Ken did both head and full figure sculptures of me, and painted me in his studio as well. They raised Morgan horses and rare birds. Later they moved with son Matt to Whidbey Island, Washington.

Ken Hassrick benefit exhibit at Rob Schouten Gallery on Whidbey Island- Feb. 1, 2010 -The Body Electric, a Ken Hassrick retrospective fundraising exhibit to benefit the Whidbey Island Arts Council. The exhibit was open to the public February 5 through March 3. In keeping with Hassrick's wish to have his work benefit the artists of Whidbey Island, his son Matt Hassrick and Matt's wife, Vicky, generously donated a large body of Ken's paintings to the Whidbey Island Arts Council. Proceeds from this retrospective went to the WIAC and be used for their many fine programs including scholarships and the development of arts education in our island schools.

What an artist leaves behind, besides his family, is the work that becomes his legacy. Longtime South Whidbey resident Ken Hassrick was an accomplished and prolific painter and sculptor. When he died in 2004, he left behind a large body of work that spanned more than 30 years, mainly paintings and drawings of the female form. In 2002, Hassrick was seriously stricken with a neurological disease which prevented him from producing more work. At that time, he told his family and friends that he wanted the proceeds from his work to benefit the art community on Whidbey Island after his death. In keeping with his father’s request, islander Matt Hassrick and his wife, Vicky, have generously donated many of Ken Hassrick’s paintings to the Whidbey Island Arts Council. Now, a show of the artist’s work is revealed in the spirit of giving back to all of the island’s artists.

“My father lived and breathed doing his art,” Matt Hassrick said. “For my entire life with him, his main focus was his art. But he was very interested in other people, too, and what they were doing,” the artist’s son said. “His door was always open for people to come over and visit, have a martini and talk about the meaning of life.” That interest in others spilled over into Ken Hassrick’s interest in art. When he moved to the island in 1978, Hassrick, along with his wife Doll, plunged into a life of art and support of the arts on Whidbey. Doll Hassrick served as president of what was then the Island Arts Council for three years. In lieu of the artist’s wishes, proceeds from this retrospective will go to the Whidbey Island Arts Council and will be used for its various supportive programs including artists’ scholarships, grants and the development of arts education in island schools.

In addition to satisfying his intent to support other artists, Hassrick probably would have appreciated the title of the show. The paintings celebrate the beauty of what the 19th century American poet Walt Whitman called “The Body Electric,” the vessel through which one’s spirit experiences the world. “I have chosen at this time in my life to express my ideas by means of the female figure,” Hassrick said when interviewed during his career. “It is without doubt one of the most complicated and ever-variable subjects. I hope you will find some of the excitement and enjoyment that I found in creating them.” Hassrick would spend almost half a lifetime exploring the evocative nature of the figure. The female body has long been one of the classic subjects for artists, and is both luminous and illuminating when it is mastered by a skilled artist. This retrospective of his work features figurative compositions that range from realism to the abstract. Hassrick developed a distinctive technique using layers of acrylic paint and charcoal that resulted in a unique quality of diffused light and depth of color. Strong compositions and a keen eye for cropping out unnecessary elements give the paintings a sensitivity of form. But his technique didn’t come without hard work.

In the course of his career, Hassrick studied with several renowned artists, including Joseph Presser, Richard Lehey, Hobson Pitman and Fernand Legar. He also traveled extensively in Europe, Mexico, Central America and New Zealand, where he sought out other artists and cultures, and tried to absorb different techniques. His work has been presented in solo exhibitions at the Philadelphia Art Alliance, the Foster White Gallery and the Davidson Gallery in Seattle, the Cammara Gallery in Los Angeles and the Childers Proctor Gallery in Langley. “Ken was not only a very fine artist, but he and his wife Doll generously served the community through countless events and activities that supported the arts on Whidbey,” said gallery owner Rob Schouten. “We are honored to host this retrospective of his paintings and to help in raising funds for the WIAC,” Schouten said.

While I was his model, Ken Hassrick taught me about art and what it means to be an artist. Because they were Ken & Barbara, his wife was called 'Doll', instead of Barbi. Ken always had the best studio in the area in which he lived. The Hassrick's were originally from Philadelphia, Boulder, Co. and West LA before coming to So. Oregon to raise Morgan horses for show. Though he is known for abstract scuptures, Ken did both head and full figure sculptures of me, and painted me in his studio as well. They raised Morgan horses and rare birds. Later they moved with son Matt to Whidbey Island, Washington.

Ken Hassrick benefit exhibit at Rob Schouten Gallery on Whidbey Island- Feb. 1, 2010 -The Body Electric, a Ken Hassrick retrospective fundraising exhibit to benefit the Whidbey Island Arts Council. The exhibit was open to the public February 5 through March 3. In keeping with Hassrick's wish to have his work benefit the artists of Whidbey Island, his son Matt Hassrick and Matt's wife, Vicky, generously donated a large body of Ken's paintings to the Whidbey Island Arts Council. Proceeds from this retrospective went to the WIAC and be used for their many fine programs including scholarships and the development of arts education in our island schools.

What an artist leaves behind, besides his family, is the work that becomes his legacy. Longtime South Whidbey resident Ken Hassrick was an accomplished and prolific painter and sculptor. When he died in 2004, he left behind a large body of work that spanned more than 30 years, mainly paintings and drawings of the female form. In 2002, Hassrick was seriously stricken with a neurological disease which prevented him from producing more work. At that time, he told his family and friends that he wanted the proceeds from his work to benefit the art community on Whidbey Island after his death. In keeping with his father’s request, islander Matt Hassrick and his wife, Vicky, have generously donated many of Ken Hassrick’s paintings to the Whidbey Island Arts Council. Now, a show of the artist’s work is revealed in the spirit of giving back to all of the island’s artists.

“My father lived and breathed doing his art,” Matt Hassrick said. “For my entire life with him, his main focus was his art. But he was very interested in other people, too, and what they were doing,” the artist’s son said. “His door was always open for people to come over and visit, have a martini and talk about the meaning of life.” That interest in others spilled over into Ken Hassrick’s interest in art. When he moved to the island in 1978, Hassrick, along with his wife Doll, plunged into a life of art and support of the arts on Whidbey. Doll Hassrick served as president of what was then the Island Arts Council for three years. In lieu of the artist’s wishes, proceeds from this retrospective will go to the Whidbey Island Arts Council and will be used for its various supportive programs including artists’ scholarships, grants and the development of arts education in island schools.

In addition to satisfying his intent to support other artists, Hassrick probably would have appreciated the title of the show. The paintings celebrate the beauty of what the 19th century American poet Walt Whitman called “The Body Electric,” the vessel through which one’s spirit experiences the world. “I have chosen at this time in my life to express my ideas by means of the female figure,” Hassrick said when interviewed during his career. “It is without doubt one of the most complicated and ever-variable subjects. I hope you will find some of the excitement and enjoyment that I found in creating them.” Hassrick would spend almost half a lifetime exploring the evocative nature of the figure. The female body has long been one of the classic subjects for artists, and is both luminous and illuminating when it is mastered by a skilled artist. This retrospective of his work features figurative compositions that range from realism to the abstract. Hassrick developed a distinctive technique using layers of acrylic paint and charcoal that resulted in a unique quality of diffused light and depth of color. Strong compositions and a keen eye for cropping out unnecessary elements give the paintings a sensitivity of form. But his technique didn’t come without hard work.

In the course of his career, Hassrick studied with several renowned artists, including Joseph Presser, Richard Lehey, Hobson Pitman and Fernand Legar. He also traveled extensively in Europe, Mexico, Central America and New Zealand, where he sought out other artists and cultures, and tried to absorb different techniques. His work has been presented in solo exhibitions at the Philadelphia Art Alliance, the Foster White Gallery and the Davidson Gallery in Seattle, the Cammara Gallery in Los Angeles and the Childers Proctor Gallery in Langley. “Ken was not only a very fine artist, but he and his wife Doll generously served the community through countless events and activities that supported the arts on Whidbey,” said gallery owner Rob Schouten. “We are honored to host this retrospective of his paintings and to help in raising funds for the WIAC,” Schouten said.

Victor King Thompson - Architect, Painter, Art Professor, Polo Player

Victor King Thompson - Architect, Painter [1913 - 2007]

March 20, 2007/ Victor King Thompson, 93, Stanford University professor emeritus of architecture, died at his home in Portola Valley on March 1. He joined the Stanford faculty in 1948, coordinating Stanford's architecture program and teaching art history for 25 years. Thompson also actively kept a private practice during those years, designing many private residences, the Ladera Community Church, and a planned residential community in Columbus, Ohio. During some of these years, he formed a partnership with former architecture student, Robert Peterson. Victor Thompson was born June 18, 1913 in Columbus, Ohio. He graduated from Ohio State University with degrees in fine arts and architecture, and as a first lieutenant in the U.S. Army ROTC. He then completed a year of postgraduate study at Cranbrook, Michigan, studying with Elieo Saarinen (son is Eero). He and Marianne Randall, also of Columbus, Ohio, were married June 18, 1940 in the First Congregational Church. Starting in 1941, Thompson served in the Army Corps of Engineers as an area engineer, then a post engineer, and was stationed in Lexington and Richmond, Kentucky, and then in Douglas, Arizona for three years. At the conclusion of WWII, he returned to Columbus to work for a year with an architectural firm while teaching night classes in architecture at OSU.

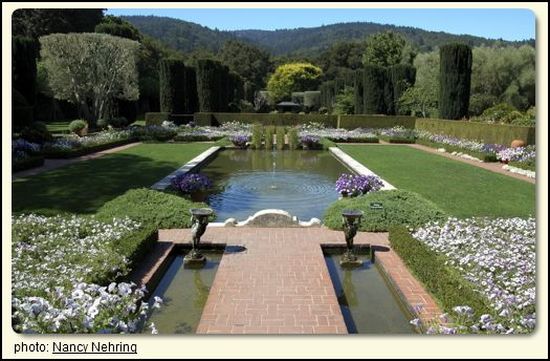

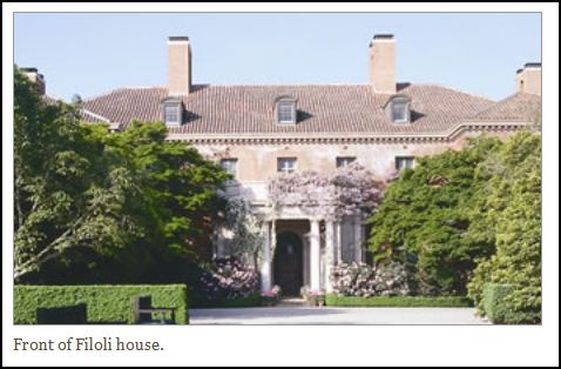

In l948, he was hired by Stanford University where he pioneered in the development of Stanford's architecture program. One of his innovations was to invite practicing architects as guest lecturers. His retirement years since the mid-1970s were full and rewarding ones in which he pursued numerous interests and activities. He was a member of the Filoli Gardens' first docent class in 1975, and then served as a docent trainer while continuing to lead tours for more than 10 years. He also served as treasurer on the board of directors for Friends of Filoli. He also volunteered as a docent for Stanford's Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve. Throughout his life, Thompson was an avid horseman, riding until his mid-80s. He was a member of the Los Altos Hunt Club and of the Menlo Polo Club. He will be remembered for his lively, generous spirit and his kind ways. He never lost his enthusiasm for life, his love of nature, and delight in travel. He is survived by his wife of 66 years, Marianne, four children, a son-in-law, and a grandson. http://www.flickr.com/photos/uaarchives/4686291010/

Thompsons Establish Scholarship Victor King Thompson 34 and Marianne Randall Thompson BA 38 have made a commitment to endow a scholarship fund for architecture students who have financial need, strong academic performance, and a talent for design. Victor has had a lifelong dedication to the study of architecture, both as an architect and as a professor at Stanford University, from which he is now retired. Marianne received a B.A. in Music from Ohio State in 1938, and is the granddaughter of William Oxley Thompson, who served from 1899 to 1925 as the fifth president of Ohio State. We have a long-term relationship with Ohio State. When I was a student in fine art, I even studied sculpture under Professor Erwin Frey, who created the sculpture of President Thompson in front of the library, Victor said. We are delighted to help a talented and deserving student. The Victor King Thompson and Marianne Randall Thompson Scholarship is a wonderful gift from a couple deeply entwined in the history of Columbus and Ohio State. With their lifelong commitment to architectural education, interdisciplinary studies, and the arts, the Thompsons exude the well-rounded knowledge with which we strive to provide the students at the Knowlton School. This scholarship will provide significant support for aspiring architects and honor the Thompsons dedication to education. Austin E. Knowlton School of Architecture KSA

DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE

OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY REGION

Richard B. Freeman [Introduction] Richard B. Freeman [Introduction]: DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY REGION. San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Art, 1949. First edition. Tall quarto. Pictorial tan boards letterpressed in black and red. Unpaginated [44 pp.] Plates and essays on a variety of paper stocks: text on pale blue uncoated pages, followed by16 pages of black and white plates on coated stock. A fine copy with very faint sunning to board edges and a slight bump to the lower corner. An uncommon and important exhibition catalog. 8.75 x 11.5 catalog from the exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art, Civic Center, San Francisco, September 16 to October 30, 1949. An important document in the history of Bay Area design, capturing a crucial moment in the development of California Architecture when the indigenous styles and imported European elements -- both contemporary (International Style) and earlier influences (Beaux Arts through Maybeck, Morgan and others) -- were being melded into a truly unique regional signature.

Contents: Introduction by Richard B. Freeman

Victor King Thompson, J. Francis Ward, Bolton White & Jack Hermann, and Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons.

March 20, 2007/ Victor King Thompson, 93, Stanford University professor emeritus of architecture, died at his home in Portola Valley on March 1. He joined the Stanford faculty in 1948, coordinating Stanford's architecture program and teaching art history for 25 years. Thompson also actively kept a private practice during those years, designing many private residences, the Ladera Community Church, and a planned residential community in Columbus, Ohio. During some of these years, he formed a partnership with former architecture student, Robert Peterson. Victor Thompson was born June 18, 1913 in Columbus, Ohio. He graduated from Ohio State University with degrees in fine arts and architecture, and as a first lieutenant in the U.S. Army ROTC. He then completed a year of postgraduate study at Cranbrook, Michigan, studying with Elieo Saarinen (son is Eero). He and Marianne Randall, also of Columbus, Ohio, were married June 18, 1940 in the First Congregational Church. Starting in 1941, Thompson served in the Army Corps of Engineers as an area engineer, then a post engineer, and was stationed in Lexington and Richmond, Kentucky, and then in Douglas, Arizona for three years. At the conclusion of WWII, he returned to Columbus to work for a year with an architectural firm while teaching night classes in architecture at OSU.

In l948, he was hired by Stanford University where he pioneered in the development of Stanford's architecture program. One of his innovations was to invite practicing architects as guest lecturers. His retirement years since the mid-1970s were full and rewarding ones in which he pursued numerous interests and activities. He was a member of the Filoli Gardens' first docent class in 1975, and then served as a docent trainer while continuing to lead tours for more than 10 years. He also served as treasurer on the board of directors for Friends of Filoli. He also volunteered as a docent for Stanford's Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve. Throughout his life, Thompson was an avid horseman, riding until his mid-80s. He was a member of the Los Altos Hunt Club and of the Menlo Polo Club. He will be remembered for his lively, generous spirit and his kind ways. He never lost his enthusiasm for life, his love of nature, and delight in travel. He is survived by his wife of 66 years, Marianne, four children, a son-in-law, and a grandson. http://www.flickr.com/photos/uaarchives/4686291010/

Thompsons Establish Scholarship Victor King Thompson 34 and Marianne Randall Thompson BA 38 have made a commitment to endow a scholarship fund for architecture students who have financial need, strong academic performance, and a talent for design. Victor has had a lifelong dedication to the study of architecture, both as an architect and as a professor at Stanford University, from which he is now retired. Marianne received a B.A. in Music from Ohio State in 1938, and is the granddaughter of William Oxley Thompson, who served from 1899 to 1925 as the fifth president of Ohio State. We have a long-term relationship with Ohio State. When I was a student in fine art, I even studied sculpture under Professor Erwin Frey, who created the sculpture of President Thompson in front of the library, Victor said. We are delighted to help a talented and deserving student. The Victor King Thompson and Marianne Randall Thompson Scholarship is a wonderful gift from a couple deeply entwined in the history of Columbus and Ohio State. With their lifelong commitment to architectural education, interdisciplinary studies, and the arts, the Thompsons exude the well-rounded knowledge with which we strive to provide the students at the Knowlton School. This scholarship will provide significant support for aspiring architects and honor the Thompsons dedication to education. Austin E. Knowlton School of Architecture KSA

DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE

OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY REGION

Richard B. Freeman [Introduction] Richard B. Freeman [Introduction]: DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY REGION. San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Art, 1949. First edition. Tall quarto. Pictorial tan boards letterpressed in black and red. Unpaginated [44 pp.] Plates and essays on a variety of paper stocks: text on pale blue uncoated pages, followed by16 pages of black and white plates on coated stock. A fine copy with very faint sunning to board edges and a slight bump to the lower corner. An uncommon and important exhibition catalog. 8.75 x 11.5 catalog from the exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art, Civic Center, San Francisco, September 16 to October 30, 1949. An important document in the history of Bay Area design, capturing a crucial moment in the development of California Architecture when the indigenous styles and imported European elements -- both contemporary (International Style) and earlier influences (Beaux Arts through Maybeck, Morgan and others) -- were being melded into a truly unique regional signature.

Contents: Introduction by Richard B. Freeman

- The Architecture of the Bay Region by Lewis Mumford

- Backgrounds and Beginnings by Elizabeth Kendall Thompson

- A Personal View by William W. Wurster

- The Post-War House by Gardner Dailey

- The Contribution of the Client by Francis Joseph McCarthy

- The Japanese Influence by Clarence W. W. Mayhew

- 26 black and white plates of some of the 51 houses selected for the exhibition, then descriptions of each house.

- Chronology

- A Catalogue Raisonne Of The Exhibition.

Victor King Thompson, J. Francis Ward, Bolton White & Jack Hermann, and Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons.

Victor King Thompson - Docent, Filoli

Victor's love of beautiful surroundings was reflected in his long-term volunteer relationship with Filoli House and Gardens. The facade was made famous as the Carrington House on Dynasty and the estate has appeared in many films and TV shows. The Gardens are internationally known.

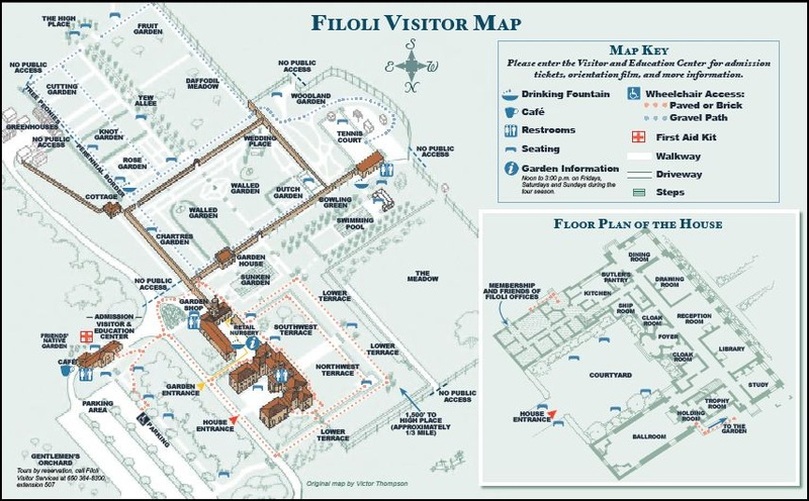

The visitors map was rendered by Thompson and artfully describes the various settings of the property and grounds.

Thompson and his wife traveled extensively and he amassed a huge photographic archive of the art and architecture of Europe and elsewhere. For a time, he lived at Clivedon House in Britain with his family in a visiting residency for Stanford.

The visitors map was rendered by Thompson and artfully describes the various settings of the property and grounds.

Thompson and his wife traveled extensively and he amassed a huge photographic archive of the art and architecture of Europe and elsewhere. For a time, he lived at Clivedon House in Britain with his family in a visiting residency for Stanford.

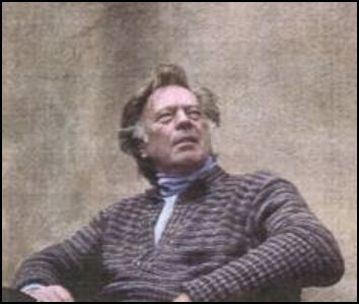

Morris Graves - American Master, Mystic

" I paint to evolve a changing language of symbols, a language with which to remark upon the qualities of our mysterious capacities which direct us toward ultimate reality." --Morris Graves

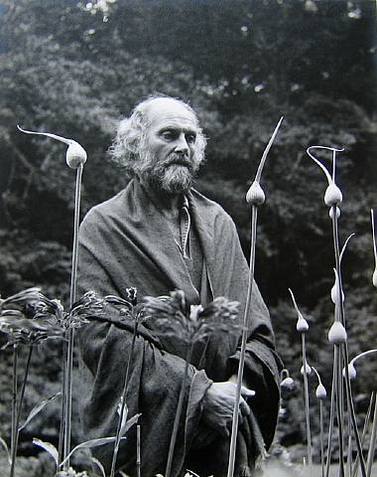

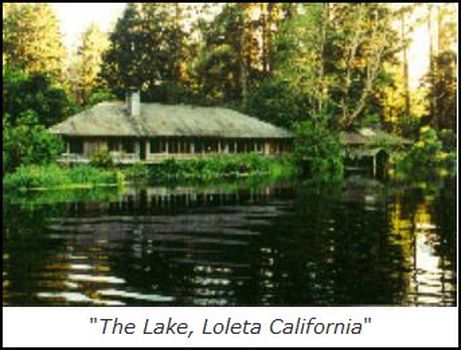

Morris Cole Graves (August 28, 1910 – May 5, 2001) was an American expressionist painter. Along with Guy Anderson, Kenneth Callahan, William Cumming, and Mark Tobey, he founded the Northwest School. Graves was also a mystic .Graves moved to Loleta, California, near Eureka in 1964 where he eventually had a home constructed that was designed by Ibsen Nelson. Internationally recognized Northwest artist Morris Graves was a resident of Humboldt County from 1964 until his death in 2001. Mr. Graves was an enduring supporter of the Humboldt Arts Council and in 1999 endowed the art museum in his name. Much of his personal collection and seven of his major and minor paintings are part of the Humboldt Arts Council's permanent collection.

His later paintings were increasingly abstract, and while they retained their delicacy, the Asian influence was gone. In later years and especially at the end of his notable career, Graves returned to sculpture, originally created forty years earlier, and received critical acclaim for his "Instruments of a New Navigation," works inspired by NASA and space exploration.Morris Graves died the morning of May 5, 2001 at his home in Loleta, hours after suffering a stroke.

http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/graves_morris.html The inspiration for the Mystic Sons is Morris Graves himself, an octogenarian artist residing in blissful isolation on a picturesque estate in northern California. A Seattle native and struggling regional artist, Graves rose to national attention as the focus of a feature article in LIFE magazine in 1953 titled "Northwest Mystics." The story detailed an emerging art movement, with Graves at the center, informed by Eastern philosophies and the natural beauty of the Pacific Rim in a charming and mysterious genre. The impact of this "Northwest Mystics School" was felt for decades, enhanced by the elegance and eloquence of its primary practitioner. Graves became something of a fixture in global high society. His work was featured in galleries and museums throughout the world, and his entourage included the biggest celebrities of the day, from movie stars to royalty. In 1957 he became the only American artist to be honored with the prestigious Windsor Award, presented personally by the Duke and Duchess themselves.

His later paintings were increasingly abstract, and while they retained their delicacy, the Asian influence was gone. In later years and especially at the end of his notable career, Graves returned to sculpture, originally created forty years earlier, and received critical acclaim for his "Instruments of a New Navigation," works inspired by NASA and space exploration.Morris Graves died the morning of May 5, 2001 at his home in Loleta, hours after suffering a stroke.

http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/graves_morris.html The inspiration for the Mystic Sons is Morris Graves himself, an octogenarian artist residing in blissful isolation on a picturesque estate in northern California. A Seattle native and struggling regional artist, Graves rose to national attention as the focus of a feature article in LIFE magazine in 1953 titled "Northwest Mystics." The story detailed an emerging art movement, with Graves at the center, informed by Eastern philosophies and the natural beauty of the Pacific Rim in a charming and mysterious genre. The impact of this "Northwest Mystics School" was felt for decades, enhanced by the elegance and eloquence of its primary practitioner. Graves became something of a fixture in global high society. His work was featured in galleries and museums throughout the world, and his entourage included the biggest celebrities of the day, from movie stars to royalty. In 1957 he became the only American artist to be honored with the prestigious Windsor Award, presented personally by the Duke and Duchess themselves.

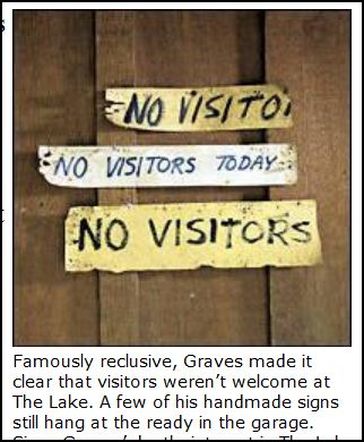

"THE LAKE" in Loleta - NO VISITORS -

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/pacificnw/2001/1209/cover.html

The House That Morris Graves Built

Aside from one picture featuring the artist, no photographs of Morris Graves' California retreat at The Lake have ever been published. The ones accompanying this story - taken by Pacific Northwest magazine photographer Benjamin Benschneider - are the first.

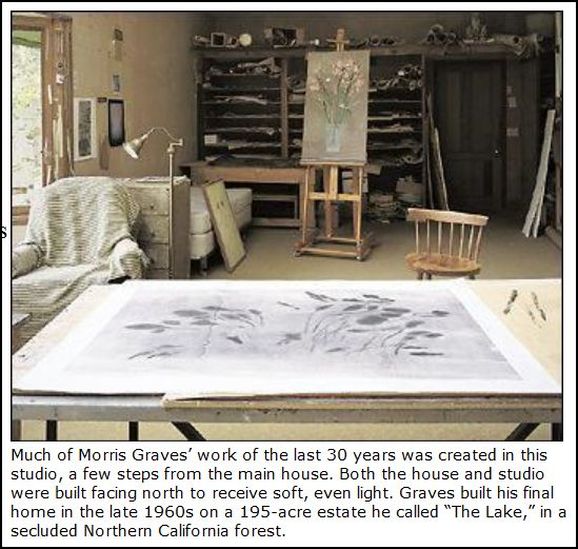

Much of Morris Graves’ work of the last 30 years was created in this studio, a few steps from the main house. Both the house and studio were built facing north to receive soft, even light. Graves built his final home in the late 1960s on a 195-acre estate he called “The Lake,” in a secluded Northern California forest. On a cloudy afternoon, the lake looks dense and as silver-black as a pool of mercury. Miniature islands sprout from the deep, and clusters of water lilies hug the shore against a fringe of cattails, ferns and giant skunk-cabbage leaves. A crystalline reflection of islands and sky shimmers on the surface, even as the surrounding forest dissolves into fog. It feels as though we've arrived at some mythic fen at the edge of the world. This is my first glimpse of the habitat of that rare and elusive creature, Morris Graves. One of the Northwest's most revered artists — and certainly the most legendary — Graves spent the last 35 years of his life at The Lake, this remote 195-acre estate in Loleta, Calif. Graves died here in May at the age of 90 and set off a tsunami of nostalgia for the glory days of Northwest art, the days when the Museum of Modern Art and its employees bought up Graves paintings by the dozens and Life magazine made famous "The Mystic Painters of the Northwest." A charismatic personality and world-renowned artist, Graves lived a life that vacillated between the utter seclusion of his several forest abodes and a glamorous dalliance with the cream of international society. For a time during the 1950s, Graves and his companion Richard Svare lived in Ireland and were entertained by such celebrities as the Rothschilds, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and American movie director John Huston. Throughout his house are notes Graves wrote to himself and to Lake manager Robert Yarber, some inspirational, some funny, some sad. In the Northwest, Graves became as famous for the amazing houses he built as for his introspective paintings. But few ever saw these places, and the public was generally excluded. At the California home that was his last, Graves maintained a heavy veil of secrecy. Stories abound about his reclusiveness: He would bodily throw out guests who displeased him, and he kept handwritten signs posted at the entrance to the property. One of them read, "No visitors today, tomorrow, or the day after." The signs stayed up year-round.

So it was with gratitude that I accepted an invitation to visit this special place with Svare and Graves' friend Jan Thompson, both of Seattle. Graves' executor, Robert Yarber, who lives at The Lake and has managed it since the early 1970s, extended the offer as a way of allowing us to pay our final respects. But the invitation presented another opportunity. To truly understand the artist's work, it's important to know something about how he lived. The trip would give us the chance to publish the first documentation of Graves' houses, a rare look at the artist's personal and most encompassing art. COURTESY OF ROBERT YARBER In a 1940s snapshot, Graves sits in the bay window of his legendary studio, The Rock, on Fidalgo Island near Anacortes. Just weeks after Graves’ death in May, The Rock burned to the ground. ALTHOUGH WE'VE arrived in California, our story begins in the Northwest, where Graves was born and grew up. Everywhere he lived as an adult — whether in a burnt-out house in La Conner, a country estate in Ireland, or the three houses he built for himself in Western Washington and California — he created something extraordinary. As his artistic fame grew, he spent progressively more of his energy and funds adapting his surroundings to suit his compulsive inner vision.

Sadly, we can't go back to see the very earliest studio the artist built for himself — it's long since been lost. Built with the help of Graves' brothers on the family property in Edmonds, it was a place his friend, the painter Guy Anderson, remembered as "a very excellent studio" in a French-provincial style. The small stone, lumber and shake structure burned down in 1935, the same year it was built. Graves was 25 at the time, and the following year he had his first solo show at the Seattle Art Museum.

For a while, Graves hung out in Seattle, living the Bohemian life. He camped out in the servant's quarters of an old mansion, shared a home on Capitol Hill with some artist friends, lived in a derelict house near Pioneer Square. He traveled a lot, but was always drawn back to this city.

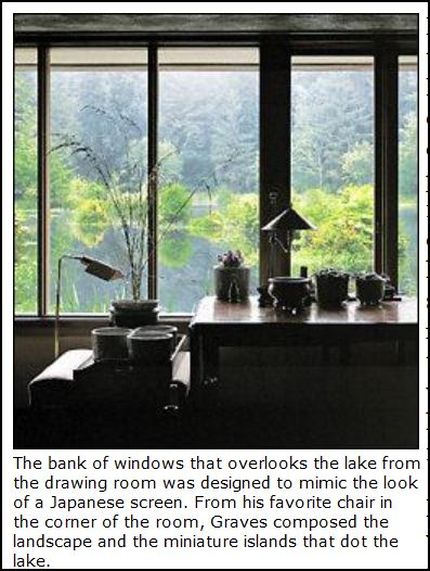

It wasn't until the late 1930s that the legends about Graves' living spaces really took hold. That's when he moved to La Conner and set up residence in an abandoned two-story Victorian partly gutted by fire. The bank of windows that overlooks the lake from the drawing room was designed to mimic the look of a Japanese screen. From his favorite chair in the corner of the room, Graves composed the landscape and the miniature islands that dot the lake.

I've never found a photograph of it, but stories about that house remain an integral part of Northwest art lore. It was a ghostly place. Graves covered the floor of one room with sand and placed rocks and driftwood to make a kind of indoor garden. He painted a huge, lifelike eye on the ceiling. Several fledgling crows that Graves kidnapped had free run of the place. One enterprising local boy found the house so bizarre that, when the artist was away, he sold tours of it for a quarter. But by living there rent-free, Graves was able to scrape together money to buy his own tract of land. At that time, 40 bucks was enough to buy him some acreage on a wooded hilltop near Deception Pass, where Graves built his first house. He called it The Rock.

It was an austere cabin — no electricity, no running water — sited on a solid stone promontory overlooking Campbell Lake. Every aspect — the Japanese-style gardens, the rough-hewn lumber of the house, the spare furnishings — had meaning to Graves. This remote house, the first Graves created from the ground up, was to change his outlook and his art. He told one writer, "I had found a way of life."

By this time he was already a mythic figure in Northwest art circles: tall, handsome, reclusive, both charming and outrageous in his social dealings. The Rock came to epitomize both Graves' startling sense of beauty — always incorporating something provocative or unexpected — and his taste for opulent asceticism. The artist owned very little furniture at the time, but the odd, worn pieces he scavenged were unfailingly gorgeous. Decades after Graves had left The Rock, that cabin and property remained an emblem of his style and a site of pilgrimage for other artists. While hitch-hiking through Northern California in 1973, Yarber met Graves and has worked for him ever since, now as director of the Morris Graves Foundation. One never-ending part of his work involves keeping the lake clear of milfoil and other prolific water plants. From then on, Graves alternated cycles of painting with the intensive labor of building and gardening. He believed that every aspect of life should be creative, whether it was plumbing or making paintings. And in each of his houses thereafter, Graves had the means to carry his vision a step further.

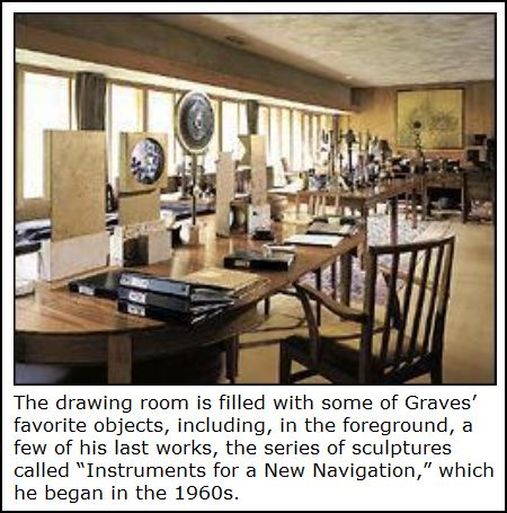

In the late 1940s, Graves moved to Woodway Park in Edmonds, and built a more ambitious house. He called it Careläden. (Graves added the umlaut and pronounced it "Carelahden" for added drama.) Set among acres of trees, the graciously proportioned cement-block structure was designed with help from architects Robert Jorgensen and Robert Shields. "Serene" is the word Svare uses to describe the house, where Graves was living when they first met. "The house at Woodway was so beautiful. The inside was all wood that we rubbed with lye and waxed by hand: It created a warmth," Svare recalls. The extensive grounds included a gatehouse, courtyard, pond and garden pavilion. Eventually, though, the postwar building boom drove Graves away from the idyllic spot, when bulldozers and chainsaws began ripping up the woods around his property for new development. The artist's anger over the encroachment is documented in his powerful "Machine Age Noise" paintings from this period. When Graves and Svare left there in 1954 to move to Ireland, poet Theodore Roethke and his wife Beatrice rented the house. The drawing room is filled with some of Graves’ favorite objects, including, in the foreground, a few of his last works, the series of sculptures called “Instruments for a New Navigation,” which he began in the 1960s. In Ireland, Graves and Svare eventually purchased an abandoned 35-acre country estate, Woodtown Manor, with a large stone house, built in 1750, that had fallen into ruin and was being used to shelter livestock. "The floors were all gone; we put in central heating, windows, all that," Svare recalls. Unlike Graves' rustic homes in the Northwest forest, this country gentleman's house and walled garden allowed Graves, with his increasing celebrity and resources, to live in a more princely style. He and Svare began to accumulate objects — Chippendale sofas and a chaise upholstered in plum velvet, 18th-century Hogarth chairs and beautiful Sheffield silver candlesticks.

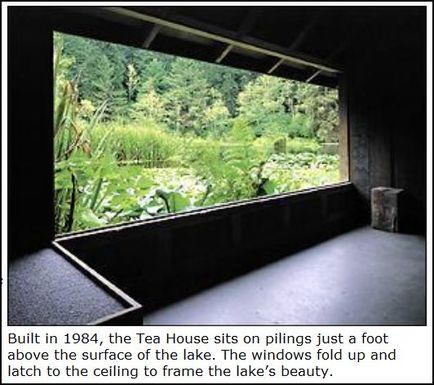

In 1965, Svare left Ireland to start a theater company in Scandinavia. A year later, Graves sold Woodtown Manor and returned to Seattle. He'd already heard about a fabulous piece of property near Eureka, and soon focused his attention on acquiring it. Built in 1984, the Tea House sits on pilings just a foot above the surface of the lake. The windows fold up and latch to the ceiling to frame the lake’s beauty.

acific Northwest magazine staff photographer.

Aside from one picture featuring the artist, no photographs of Morris Graves' California retreat at The Lake have ever been published. The ones accompanying this story - taken by Pacific Northwest magazine photographer Benjamin Benschneider - are the first.

Much of Morris Graves’ work of the last 30 years was created in this studio, a few steps from the main house. Both the house and studio were built facing north to receive soft, even light. Graves built his final home in the late 1960s on a 195-acre estate he called “The Lake,” in a secluded Northern California forest. On a cloudy afternoon, the lake looks dense and as silver-black as a pool of mercury. Miniature islands sprout from the deep, and clusters of water lilies hug the shore against a fringe of cattails, ferns and giant skunk-cabbage leaves. A crystalline reflection of islands and sky shimmers on the surface, even as the surrounding forest dissolves into fog. It feels as though we've arrived at some mythic fen at the edge of the world. This is my first glimpse of the habitat of that rare and elusive creature, Morris Graves. One of the Northwest's most revered artists — and certainly the most legendary — Graves spent the last 35 years of his life at The Lake, this remote 195-acre estate in Loleta, Calif. Graves died here in May at the age of 90 and set off a tsunami of nostalgia for the glory days of Northwest art, the days when the Museum of Modern Art and its employees bought up Graves paintings by the dozens and Life magazine made famous "The Mystic Painters of the Northwest." A charismatic personality and world-renowned artist, Graves lived a life that vacillated between the utter seclusion of his several forest abodes and a glamorous dalliance with the cream of international society. For a time during the 1950s, Graves and his companion Richard Svare lived in Ireland and were entertained by such celebrities as the Rothschilds, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and American movie director John Huston. Throughout his house are notes Graves wrote to himself and to Lake manager Robert Yarber, some inspirational, some funny, some sad. In the Northwest, Graves became as famous for the amazing houses he built as for his introspective paintings. But few ever saw these places, and the public was generally excluded. At the California home that was his last, Graves maintained a heavy veil of secrecy. Stories abound about his reclusiveness: He would bodily throw out guests who displeased him, and he kept handwritten signs posted at the entrance to the property. One of them read, "No visitors today, tomorrow, or the day after." The signs stayed up year-round.

So it was with gratitude that I accepted an invitation to visit this special place with Svare and Graves' friend Jan Thompson, both of Seattle. Graves' executor, Robert Yarber, who lives at The Lake and has managed it since the early 1970s, extended the offer as a way of allowing us to pay our final respects. But the invitation presented another opportunity. To truly understand the artist's work, it's important to know something about how he lived. The trip would give us the chance to publish the first documentation of Graves' houses, a rare look at the artist's personal and most encompassing art. COURTESY OF ROBERT YARBER In a 1940s snapshot, Graves sits in the bay window of his legendary studio, The Rock, on Fidalgo Island near Anacortes. Just weeks after Graves’ death in May, The Rock burned to the ground. ALTHOUGH WE'VE arrived in California, our story begins in the Northwest, where Graves was born and grew up. Everywhere he lived as an adult — whether in a burnt-out house in La Conner, a country estate in Ireland, or the three houses he built for himself in Western Washington and California — he created something extraordinary. As his artistic fame grew, he spent progressively more of his energy and funds adapting his surroundings to suit his compulsive inner vision.

Sadly, we can't go back to see the very earliest studio the artist built for himself — it's long since been lost. Built with the help of Graves' brothers on the family property in Edmonds, it was a place his friend, the painter Guy Anderson, remembered as "a very excellent studio" in a French-provincial style. The small stone, lumber and shake structure burned down in 1935, the same year it was built. Graves was 25 at the time, and the following year he had his first solo show at the Seattle Art Museum.

For a while, Graves hung out in Seattle, living the Bohemian life. He camped out in the servant's quarters of an old mansion, shared a home on Capitol Hill with some artist friends, lived in a derelict house near Pioneer Square. He traveled a lot, but was always drawn back to this city.

It wasn't until the late 1930s that the legends about Graves' living spaces really took hold. That's when he moved to La Conner and set up residence in an abandoned two-story Victorian partly gutted by fire. The bank of windows that overlooks the lake from the drawing room was designed to mimic the look of a Japanese screen. From his favorite chair in the corner of the room, Graves composed the landscape and the miniature islands that dot the lake.

I've never found a photograph of it, but stories about that house remain an integral part of Northwest art lore. It was a ghostly place. Graves covered the floor of one room with sand and placed rocks and driftwood to make a kind of indoor garden. He painted a huge, lifelike eye on the ceiling. Several fledgling crows that Graves kidnapped had free run of the place. One enterprising local boy found the house so bizarre that, when the artist was away, he sold tours of it for a quarter. But by living there rent-free, Graves was able to scrape together money to buy his own tract of land. At that time, 40 bucks was enough to buy him some acreage on a wooded hilltop near Deception Pass, where Graves built his first house. He called it The Rock.

It was an austere cabin — no electricity, no running water — sited on a solid stone promontory overlooking Campbell Lake. Every aspect — the Japanese-style gardens, the rough-hewn lumber of the house, the spare furnishings — had meaning to Graves. This remote house, the first Graves created from the ground up, was to change his outlook and his art. He told one writer, "I had found a way of life."

By this time he was already a mythic figure in Northwest art circles: tall, handsome, reclusive, both charming and outrageous in his social dealings. The Rock came to epitomize both Graves' startling sense of beauty — always incorporating something provocative or unexpected — and his taste for opulent asceticism. The artist owned very little furniture at the time, but the odd, worn pieces he scavenged were unfailingly gorgeous. Decades after Graves had left The Rock, that cabin and property remained an emblem of his style and a site of pilgrimage for other artists. While hitch-hiking through Northern California in 1973, Yarber met Graves and has worked for him ever since, now as director of the Morris Graves Foundation. One never-ending part of his work involves keeping the lake clear of milfoil and other prolific water plants. From then on, Graves alternated cycles of painting with the intensive labor of building and gardening. He believed that every aspect of life should be creative, whether it was plumbing or making paintings. And in each of his houses thereafter, Graves had the means to carry his vision a step further.

In the late 1940s, Graves moved to Woodway Park in Edmonds, and built a more ambitious house. He called it Careläden. (Graves added the umlaut and pronounced it "Carelahden" for added drama.) Set among acres of trees, the graciously proportioned cement-block structure was designed with help from architects Robert Jorgensen and Robert Shields. "Serene" is the word Svare uses to describe the house, where Graves was living when they first met. "The house at Woodway was so beautiful. The inside was all wood that we rubbed with lye and waxed by hand: It created a warmth," Svare recalls. The extensive grounds included a gatehouse, courtyard, pond and garden pavilion. Eventually, though, the postwar building boom drove Graves away from the idyllic spot, when bulldozers and chainsaws began ripping up the woods around his property for new development. The artist's anger over the encroachment is documented in his powerful "Machine Age Noise" paintings from this period. When Graves and Svare left there in 1954 to move to Ireland, poet Theodore Roethke and his wife Beatrice rented the house. The drawing room is filled with some of Graves’ favorite objects, including, in the foreground, a few of his last works, the series of sculptures called “Instruments for a New Navigation,” which he began in the 1960s. In Ireland, Graves and Svare eventually purchased an abandoned 35-acre country estate, Woodtown Manor, with a large stone house, built in 1750, that had fallen into ruin and was being used to shelter livestock. "The floors were all gone; we put in central heating, windows, all that," Svare recalls. Unlike Graves' rustic homes in the Northwest forest, this country gentleman's house and walled garden allowed Graves, with his increasing celebrity and resources, to live in a more princely style. He and Svare began to accumulate objects — Chippendale sofas and a chaise upholstered in plum velvet, 18th-century Hogarth chairs and beautiful Sheffield silver candlesticks.

In 1965, Svare left Ireland to start a theater company in Scandinavia. A year later, Graves sold Woodtown Manor and returned to Seattle. He'd already heard about a fabulous piece of property near Eureka, and soon focused his attention on acquiring it. Built in 1984, the Tea House sits on pilings just a foot above the surface of the lake. The windows fold up and latch to the ceiling to frame the lake’s beauty.

acific Northwest magazine staff photographer.

Sheila Farr; The Seattle Times art critic

On a cloudy afternoon, the lake looks dense and as silver-black as a pool of mercury. Miniature islands sprout from the deep, and clusters of water lilies Water Lilies (or Nympheas) is a series of approximately 250 oil paintings by French Impressionist Claude Monet (1840-1926). The paintings depict Monet's flower garden at Giverny and were the main focus of Monet's artistic production during the last thirty years hug the shore against a fringe of cattails, ferns and giant skunk-cabbage leaves. A crystalline reflection of islands and sky shimmers on the surface, even as the surrounding forest dissolves into fog. It feels as though we've arrived at some mythic fen at the edge of the world.

This is my first glimpse First Glimpse is a monthly consumer electronics magazine published by Sandhills Publishing Company in Lincoln, Nebraska, USA. The magazine was known as CE Lifestyles before a name change in early 2006. of the habitat of that rare and elusive creature, Morris Graves Morris Cole Graves (August 28, 1910 – May 5, 2001) was an American painter and a founder of the Northwest School (art). Early years

Born the sixth son of a Methodist family in Fox Valley, Oregon, Graves was a country boy. . One of the Northwest's most revered artists -- and certainly the most legendary -- Graves spent the last 35 years of his life at The Lake, this remote 195-acre estate in Loleta, Calif. Graves died here in May at the age of 90 and set off a tsunami of nostalgia for the glory days of Northwest art, the days when the Museum of Modern Art and its employees bought up Graves paintings by the dozens and Life magazine made famous "The Mystic Painters of the Northwest." A charismatic personality and world-renowned artist, Graves lived a life that vacillated between the utter seclusion seclusion Forensic psychiatry A strategy for managing disturbed and violent Pts in psychiatric units, which consists of supervised confinement of a Pt to a room–ie, involuntary isolation, to protect others from harm of his several forest abodes and a glamorous dalliance with the cream of international society. For a time during the 1950s, Graves and his companion Richard Svare lived in Ireland and were entertained by such celebrities as the Rothschilds, the Duke and Duchess For the real-world peerages, see Duke.

The Duke and Duchess of Boxford are people featured in the Thomas the Tank Engine and Friends TV Series. of Windsor, and American movie director John Huston.

In the Northwest, Graves became as famous for the amazing houses he built as for his introspective paintings. But few ever saw these places, and the public was generally excluded. At the California home that was his last, Graves maintained a heavy veil of secrecy. Stories abound about his reclusiveness

To cause annoyance or displeasure. him, and he kept handwritten signs posted at the entrance to the property. One of them read, "No visitors today, tomorrow, or the day after." The signs stayed up year-round.

So it was with gratitude that I accepted an invitation to visit this special place with Svare and Graves' friend Jan Thompson, both of Seattle. Graves' executor, Robert Yarber Robert Yarber (born Dallas, Texas, 1948) is an American painter and Distinguished Professor of Art at Pennsylvania State University. He received a BFA from Cooper Union in 1971, and a MFA from Louisiana State University in 1973. , who lives at The Lake and has managed it since the early 1970s, extended the offer as a way of allowing us to pay our final respects. But the invitation presented another opportunity. To truly understand the artist's work, it's important to know something about how he lived. The trip would give us the chance to publish the first documentation of Graves' houses, a rare look at the artist's personal and most encompassing art. THE WAY GRAVES integrated the buildings and landscape at The Lake is spectacular. We stand transfixed in the spacious drawing room of the main house, which cantilevers over the water on pilings and seems to drift among the reeds and water lilies. A bank of tall windows stretches the expanse of the 50-foot room, like the panels of a Japanese screen. This is where, from a chair in the south corner, the artist would sit, overlooking his floating world. A few steps out a side door would take the painter to his studio and a small boat house. From there a trail leads on to Yarber's house. On the opposite shore stands a guest house and a Japanese-style teahouse, tucked among the cattails. Behind the L-shaped main house, Graves' formal garden, composed around a geometry of boxwood boxwood

see buxus sempervirens. hedges, lies abandoned where his leeks, flowers and vegetables once grew. Even when he was actively gardening, though, Graves liked a little disorder. He built his gardens on Japanese principles, emphasizing mystery, rustic solitude and a reminder that whatever grows also dies.

"He liked the look of an abandoned garden that had been tended and formalized for·mal·ize

tr.v. for·mal·ized, for·mal·iz·ing, for·mal·iz·es

1. To give a definite form or shape to.

2.

a. To make formal.

b. , then let go -- but not too far," Yarber says.

Thompson, who drove down with Graves from Seattle when he purchased the property, recalls his fascination with the site. "We drove up to the top of that little hill, then walked in because the road wasn't built. He was absolutely in a trance. He squatted by the lake for hours just looking -- it was full of logs and junk. To me, it was a mess: He had a vision of it that I couldn't see." The first order of business was clearing the lake, and Graves worked at it to the point of exhaustion, diving down and pulling out logs and weeds. "He composed it to be serene," Yarber says.

Now, when you look out from the drawing room, the view is otherworldly. Sighs of mist lift off the lake like spirits rising from the deep. The remains of an ancient, submerged forest lie here, and each miniature island sprouts from the decaying mass of a tree whose trunk, preserved by water, still reaches down some 30 feet to the lake floor. Yarber explains that an earthquake 300 years ago created a sag-pond. "That's when the land gives way, forming a bowl that fills with water. Over the decades and centuries, the tree trunks rotted down and formed humus and then wind and birds dropped native seeds. It's very fertile, but because of the limited space, they've taken a stunted growth It's a natural bonsai garden."

You can see why Graves had to have this piece of land. It's the same kind of secluded, forest landscape he always chose for himself when he lived and painted in the Seattle area -- only more so. By the time Graves purchased the extravagant piece of property, he was in his 50s, and commanded high prices for his work. The scale of this project was huge compared with the two other houses he built. Here at The Lake he could shape an entire landscape: He owned everything his eye could see. When he bought the property, he told Thompson, "I have one more house in me."

Building the place to suit his exacting vision took everything Graves had, and then some. An audacious man, he was always willing to spend all his resources of strength, money, inspiration and time to create something of exceeding beauty. But this time, with unforeseen construction bills piling up, the artist, desperate, had to ask his friends to help by selling pictures he had given them as gifts. Both Thompson and Svare complied. And Graves himself parted with the entire contents of a trunk containing hundreds of his early drawings, sketches, studies and paintings, which he sold en masse to Portland collector Virginia Haseltine. She donated the work to the University of Oregon The University of Oregon is a public university located in Eugene, Oregon. The university was founded in 1876, graduating its first class two years later. The University of Oregon is one of 60 members of the Association of American Universities. .

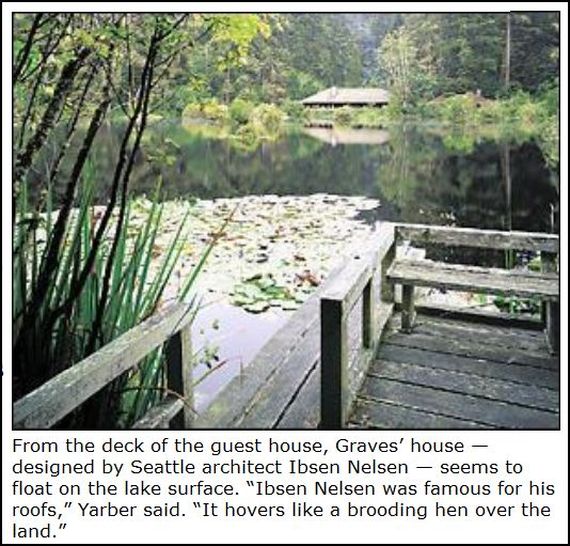

The runaway budget was the source of a major falling out between Graves and Seattle architect Ibsen Nelsen, who collaborated with him on the house. Graves chose Nelsen impetuously. administration building that Nelsen designed in the early '60s near the UW campus, he was swept away. "He saw this building, walked in and asked who built it, then went straight over to Ibsen's office and asked to talk to him," Hans says. The architect and the artist began their collaboration enthusiastically. As construction progressed, however, each blamed the other for cost overruns as the budget ballooned to twice the original amount.

Part of that was because Graves insisted on the house being sited within six feet of the shore, even when it turned out the ground was unstable. Graves acknowledged responsibility for that initial expense, but told Thompson and other friends that Nelsen had opted for more expensive building materials than they had agreed on. Whatever happened, by the end of the project, the two weren't speaking. Graves never paid the architect his fee, although he did, some years later, send him a painting. Despite the problems, Nelsen told a Seattle art historian he didn't regret doing it. "It was the best house that he did without a doubt, and he knew that," Hans says. "And it was Morris's influence. The way that building worked and how it was sited, its whole feeling and ambience -- a lot of that was Morris." Still estranged the two men died within months of each other this year.

WRITING ABOUT Graves' houses is a difficult task. I hesitate to breach the privacy he so strenuously maintained, and yet his estate at The Lake is at the brink of a new incarnation. As director of the Morris Graves Foundation, Yarber, 50, will open up the house and studio by invitation to select artists, writers and musicians for work and study. He is planning to selectively log some trees, replace the redwood shingle roof with metal, and install skylights to illuminate the house. With its northern exposure and steep, overhanging roof, the house stays perennially dark and prone to dampness, even with its several fireplaces and woodstoves crackling constantly to keep off the chill.

Although The Lake will remain, perhaps it's fitting that traces of its enigmatic owner disappear. Thirty years ago Graves complained to a critic about performance artists who felt the need to record their work for posterity. He said documentation was the antithesis of his purpose, which he maintained was spontaneous and private. Some of Graves' old friends recalled his philosophy last May when, eerily, just weeks after Graves' death, his cabin at The Rock caught fire and burned to the ground. Its caretaker, Terry Smith, died in the blaze.

Graves eventually sold Careladen in Edmonds, and, though still beautiful having passed through several owners, it exists in a much different style from the days of its first inhabitant INHABITANT. One who has his domicil in a place is an inhabitant of that place; one who has an actual fixed residence in a place.

2. A mere intention to remove to a place will not make a man an inhabitant of such place, although as a sign of such intention he .

As for Woodtown Manor, Graves sold it to a member of the Guinness brewery clan. When Svare last visited, the house had been rented to a famous rock band, its lovely interior and furnishings trashed trashed adj. Slang Drunk or intoxicated.

Our Living Language Expressions for intoxication are among those that best showcase the creativity of slang. .

Seeing The Lake as Graves left it -- where every object, every piece of furniture, every view evokes him -- has been a rare privilege. But I also found it a little depressing. By the end of his life, the austerity of the artist's early environments had given way to an accumulation of beautiful objects, too many to fully appreciate. He had ordered a vast estate to suit his need for a harmonious environment, yet that serenity remained outside him. "Morris was surrounded by so much beauty, and still it wasn't enough," Yarber said. "You could say his whole life was a three-dimensional painting -- just composing things." Noun 1. John Huston - United States film maker born in the United States but an Irish citizen after 1964 (1906-1987)

Huston

..... Click the link for more information. Building materials used in the construction industry to create .

These categories of materials and products are used by and construction project managers to specify the materials and methods used for .

..... Click the link for more information.

On a cloudy afternoon, the lake looks dense and as silver-black as a pool of mercury. Miniature islands sprout from the deep, and clusters of water lilies Water Lilies (or Nympheas) is a series of approximately 250 oil paintings by French Impressionist Claude Monet (1840-1926). The paintings depict Monet's flower garden at Giverny and were the main focus of Monet's artistic production during the last thirty years hug the shore against a fringe of cattails, ferns and giant skunk-cabbage leaves. A crystalline reflection of islands and sky shimmers on the surface, even as the surrounding forest dissolves into fog. It feels as though we've arrived at some mythic fen at the edge of the world.

This is my first glimpse First Glimpse is a monthly consumer electronics magazine published by Sandhills Publishing Company in Lincoln, Nebraska, USA. The magazine was known as CE Lifestyles before a name change in early 2006. of the habitat of that rare and elusive creature, Morris Graves Morris Cole Graves (August 28, 1910 – May 5, 2001) was an American painter and a founder of the Northwest School (art). Early years

Born the sixth son of a Methodist family in Fox Valley, Oregon, Graves was a country boy. . One of the Northwest's most revered artists -- and certainly the most legendary -- Graves spent the last 35 years of his life at The Lake, this remote 195-acre estate in Loleta, Calif. Graves died here in May at the age of 90 and set off a tsunami of nostalgia for the glory days of Northwest art, the days when the Museum of Modern Art and its employees bought up Graves paintings by the dozens and Life magazine made famous "The Mystic Painters of the Northwest." A charismatic personality and world-renowned artist, Graves lived a life that vacillated between the utter seclusion seclusion Forensic psychiatry A strategy for managing disturbed and violent Pts in psychiatric units, which consists of supervised confinement of a Pt to a room–ie, involuntary isolation, to protect others from harm of his several forest abodes and a glamorous dalliance with the cream of international society. For a time during the 1950s, Graves and his companion Richard Svare lived in Ireland and were entertained by such celebrities as the Rothschilds, the Duke and Duchess For the real-world peerages, see Duke.

The Duke and Duchess of Boxford are people featured in the Thomas the Tank Engine and Friends TV Series. of Windsor, and American movie director John Huston.

In the Northwest, Graves became as famous for the amazing houses he built as for his introspective paintings. But few ever saw these places, and the public was generally excluded. At the California home that was his last, Graves maintained a heavy veil of secrecy. Stories abound about his reclusiveness

To cause annoyance or displeasure. him, and he kept handwritten signs posted at the entrance to the property. One of them read, "No visitors today, tomorrow, or the day after." The signs stayed up year-round.

So it was with gratitude that I accepted an invitation to visit this special place with Svare and Graves' friend Jan Thompson, both of Seattle. Graves' executor, Robert Yarber Robert Yarber (born Dallas, Texas, 1948) is an American painter and Distinguished Professor of Art at Pennsylvania State University. He received a BFA from Cooper Union in 1971, and a MFA from Louisiana State University in 1973. , who lives at The Lake and has managed it since the early 1970s, extended the offer as a way of allowing us to pay our final respects. But the invitation presented another opportunity. To truly understand the artist's work, it's important to know something about how he lived. The trip would give us the chance to publish the first documentation of Graves' houses, a rare look at the artist's personal and most encompassing art. THE WAY GRAVES integrated the buildings and landscape at The Lake is spectacular. We stand transfixed in the spacious drawing room of the main house, which cantilevers over the water on pilings and seems to drift among the reeds and water lilies. A bank of tall windows stretches the expanse of the 50-foot room, like the panels of a Japanese screen. This is where, from a chair in the south corner, the artist would sit, overlooking his floating world. A few steps out a side door would take the painter to his studio and a small boat house. From there a trail leads on to Yarber's house. On the opposite shore stands a guest house and a Japanese-style teahouse, tucked among the cattails. Behind the L-shaped main house, Graves' formal garden, composed around a geometry of boxwood boxwood

see buxus sempervirens. hedges, lies abandoned where his leeks, flowers and vegetables once grew. Even when he was actively gardening, though, Graves liked a little disorder. He built his gardens on Japanese principles, emphasizing mystery, rustic solitude and a reminder that whatever grows also dies.

"He liked the look of an abandoned garden that had been tended and formalized for·mal·ize

tr.v. for·mal·ized, for·mal·iz·ing, for·mal·iz·es

1. To give a definite form or shape to.

2.

a. To make formal.

b. , then let go -- but not too far," Yarber says.

Thompson, who drove down with Graves from Seattle when he purchased the property, recalls his fascination with the site. "We drove up to the top of that little hill, then walked in because the road wasn't built. He was absolutely in a trance. He squatted by the lake for hours just looking -- it was full of logs and junk. To me, it was a mess: He had a vision of it that I couldn't see." The first order of business was clearing the lake, and Graves worked at it to the point of exhaustion, diving down and pulling out logs and weeds. "He composed it to be serene," Yarber says.

Now, when you look out from the drawing room, the view is otherworldly. Sighs of mist lift off the lake like spirits rising from the deep. The remains of an ancient, submerged forest lie here, and each miniature island sprouts from the decaying mass of a tree whose trunk, preserved by water, still reaches down some 30 feet to the lake floor. Yarber explains that an earthquake 300 years ago created a sag-pond. "That's when the land gives way, forming a bowl that fills with water. Over the decades and centuries, the tree trunks rotted down and formed humus and then wind and birds dropped native seeds. It's very fertile, but because of the limited space, they've taken a stunted growth It's a natural bonsai garden."

You can see why Graves had to have this piece of land. It's the same kind of secluded, forest landscape he always chose for himself when he lived and painted in the Seattle area -- only more so. By the time Graves purchased the extravagant piece of property, he was in his 50s, and commanded high prices for his work. The scale of this project was huge compared with the two other houses he built. Here at The Lake he could shape an entire landscape: He owned everything his eye could see. When he bought the property, he told Thompson, "I have one more house in me."

Building the place to suit his exacting vision took everything Graves had, and then some. An audacious man, he was always willing to spend all his resources of strength, money, inspiration and time to create something of exceeding beauty. But this time, with unforeseen construction bills piling up, the artist, desperate, had to ask his friends to help by selling pictures he had given them as gifts. Both Thompson and Svare complied. And Graves himself parted with the entire contents of a trunk containing hundreds of his early drawings, sketches, studies and paintings, which he sold en masse to Portland collector Virginia Haseltine. She donated the work to the University of Oregon The University of Oregon is a public university located in Eugene, Oregon. The university was founded in 1876, graduating its first class two years later. The University of Oregon is one of 60 members of the Association of American Universities. .

The runaway budget was the source of a major falling out between Graves and Seattle architect Ibsen Nelsen, who collaborated with him on the house. Graves chose Nelsen impetuously. administration building that Nelsen designed in the early '60s near the UW campus, he was swept away. "He saw this building, walked in and asked who built it, then went straight over to Ibsen's office and asked to talk to him," Hans says. The architect and the artist began their collaboration enthusiastically. As construction progressed, however, each blamed the other for cost overruns as the budget ballooned to twice the original amount.

Part of that was because Graves insisted on the house being sited within six feet of the shore, even when it turned out the ground was unstable. Graves acknowledged responsibility for that initial expense, but told Thompson and other friends that Nelsen had opted for more expensive building materials than they had agreed on. Whatever happened, by the end of the project, the two weren't speaking. Graves never paid the architect his fee, although he did, some years later, send him a painting. Despite the problems, Nelsen told a Seattle art historian he didn't regret doing it. "It was the best house that he did without a doubt, and he knew that," Hans says. "And it was Morris's influence. The way that building worked and how it was sited, its whole feeling and ambience -- a lot of that was Morris." Still estranged the two men died within months of each other this year.

WRITING ABOUT Graves' houses is a difficult task. I hesitate to breach the privacy he so strenuously maintained, and yet his estate at The Lake is at the brink of a new incarnation. As director of the Morris Graves Foundation, Yarber, 50, will open up the house and studio by invitation to select artists, writers and musicians for work and study. He is planning to selectively log some trees, replace the redwood shingle roof with metal, and install skylights to illuminate the house. With its northern exposure and steep, overhanging roof, the house stays perennially dark and prone to dampness, even with its several fireplaces and woodstoves crackling constantly to keep off the chill.

Although The Lake will remain, perhaps it's fitting that traces of its enigmatic owner disappear. Thirty years ago Graves complained to a critic about performance artists who felt the need to record their work for posterity. He said documentation was the antithesis of his purpose, which he maintained was spontaneous and private. Some of Graves' old friends recalled his philosophy last May when, eerily, just weeks after Graves' death, his cabin at The Rock caught fire and burned to the ground. Its caretaker, Terry Smith, died in the blaze.

Graves eventually sold Careladen in Edmonds, and, though still beautiful having passed through several owners, it exists in a much different style from the days of its first inhabitant INHABITANT. One who has his domicil in a place is an inhabitant of that place; one who has an actual fixed residence in a place.

2. A mere intention to remove to a place will not make a man an inhabitant of such place, although as a sign of such intention he .

As for Woodtown Manor, Graves sold it to a member of the Guinness brewery clan. When Svare last visited, the house had been rented to a famous rock band, its lovely interior and furnishings trashed trashed adj. Slang Drunk or intoxicated.

Our Living Language Expressions for intoxication are among those that best showcase the creativity of slang. .

Seeing The Lake as Graves left it -- where every object, every piece of furniture, every view evokes him -- has been a rare privilege. But I also found it a little depressing. By the end of his life, the austerity of the artist's early environments had given way to an accumulation of beautiful objects, too many to fully appreciate. He had ordered a vast estate to suit his need for a harmonious environment, yet that serenity remained outside him. "Morris was surrounded by so much beauty, and still it wasn't enough," Yarber said. "You could say his whole life was a three-dimensional painting -- just composing things." Noun 1. John Huston - United States film maker born in the United States but an Irish citizen after 1964 (1906-1987)

Huston

..... Click the link for more information. Building materials used in the construction industry to create .

These categories of materials and products are used by and construction project managers to specify the materials and methods used for .

..... Click the link for more information.

Artful Landscape

THE WAY GRAVES integrated the buildings and landscape at The Lake is spectacular. We stand transfixed in the spacious drawing room of the main house, which cantilevers over the water on pilings and seems to drift among the reeds and water lilies. A bank of tall windows stretches the expanse of the 50-foot room, like the panels of a Japanese screen. This is where, from a chair in the south corner, the artist would sit, overlooking his floating world. A few steps out a side door would take the painter to his studio and a small boat house. From there a trail leads on to Yarber's house. On the opposite shore stands a guest house and a Japanese-style teahouse, tucked among the cattails. Behind the L-shaped main house, Graves' formal garden, composed around a geometry of boxwood hedges, lies abandoned where his leeks, flowers and vegetables once grew. Even when he was actively gardening, though, Graves liked a little disorder. He built his gardens on Japanese principles, emphasizing mystery, rustic solitude and a reminder that whatever grows also dies. PHOTO BY RICHARD SVARE, COURTESY OF ROBERT YARBER In 1958, painters Jan Thompson and Richard Gilkey visit Graves (standing) at his house in Ireland called Woodtown Manor. "He liked the look of an abandoned garden that had been tended and formalized, then let go — but not too far," Yarber says.

Thompson, who drove down with Graves from Seattle when he purchased the property, recalls his fascination with the site. "We drove up to the top of that little hill, then walked in because the road wasn't built. He was absolutely in a trance. He squatted by the lake for hours just looking — it was full of logs and junk. To me, it was a mess: He had a vision of it that I couldn't see." The first order of business was clearing the lake, and Graves worked at it to the point of exhaustion, diving down and pulling out logs and weeds. "He composed it to be serene," Yarber says.

Now, when you look out from the drawing room, the view is otherworldly. Sighs of mist lift off the lake like spirits rising from the deep. The remains of an ancient, submerged forest lie here, and each miniature island sprouts from the decaying mass of a tree whose trunk, preserved by water, still reaches down some 30 feet to the lake floor. Yarber explains that an earthquake 300 years ago created a sag-pond. "That's when the land gives way, forming a bowl that fills with water. Over the decades and centuries, the tree trunks rotted down and formed humus, and then wind and birds dropped native seeds. It's very fertile, but because of the limited space, they've taken a stunted growth. It's a natural bonsai garden."

You can see why Graves had to have this piece of land. It's the same kind of secluded, forest landscape he always chose for himself when he lived and painted in the Seattle area — only more so. By the time Graves purchased the extravagant piece of property, he was in his 50s, and commanded high prices for his work. The scale of this project was huge compared with the two other houses he built. Here at The Lake he could shape an entire landscape: He owned everything his eye could see. When he bought the property, he told Thompson, "I have one more house in me." From the deck of the guest house, Graves’ house — designed by Seattle architect Ibsen Nelsen — seems to float on the lake surface. “Ibsen Nelsen was famous for his roofs,” Yarber said. “It hovers like a brooding hen over the land.” Building the place to suit his exacting vision took everything Graves had, and then some. An audacious man, he was always willing to spend all his resources of strength, money, inspiration and time to create something of exceeding beauty. But this time, with unforeseen construction bills piling up, the artist, desperate, had to ask his friends to help by selling pictures he had given them as gifts. Both Thompson and Svare complied. And Graves himself parted with the entire contents of a trunk containing hundreds of his early drawings, sketches, studies and paintings, which he sold en masse to Portland collector Virginia Haseltine. She donated the work to the University of Oregon.