THE WIZARDS OF AHS

Subculture Shenanigans

Curating the Psychedelic Cognoscenti: 1966 - 2014

Psychedelic & Neo-Psychedelic Scenes & Zines

by Iona Miller & Morgan Russell, (c)2013

With an aging boomer generation in its golden years, the curation of the history of the psychedelic revolution and ensuing scenes takes on a poignant urgency. The Underground was the matrix of numerous scenes and revivals that are still highly influential in society today, though their magic moments have come and gone. While each of the psychedelic luminaries and cyber-pioneers have their own press, an overview of some of their former and current activities highlights the arc of these rainbow warriors from many walks of life. No one has written a comprehensive overview that links the agendas of various geographically separated groups into a coherent integral overview, spanning the interactions of West Coast, East Coast, Europe, Hyperspace, and the Virtuality.

From "Dodge City" to "Quail House", from "Silicon-Alley" to Miami Beach, and Beyond

Video forthcoming

From "Dodge City" to "Quail House", from "Silicon-Alley" to Miami Beach, and Beyond

Video forthcoming

1/26/06

ANIMATION OF IO ART: DO THE OZ

click here:

http://www.sign69.com/medialounge/space721.html

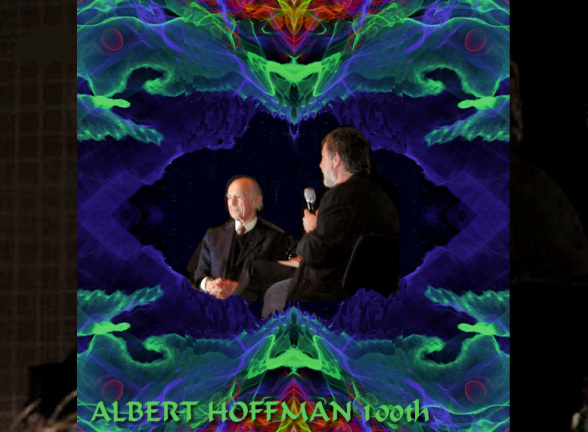

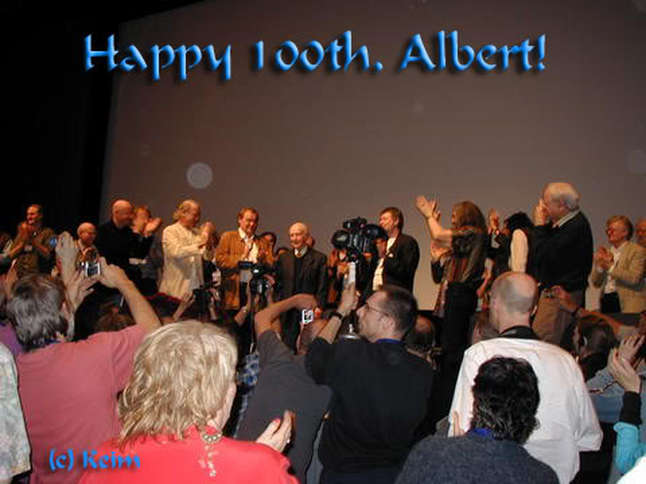

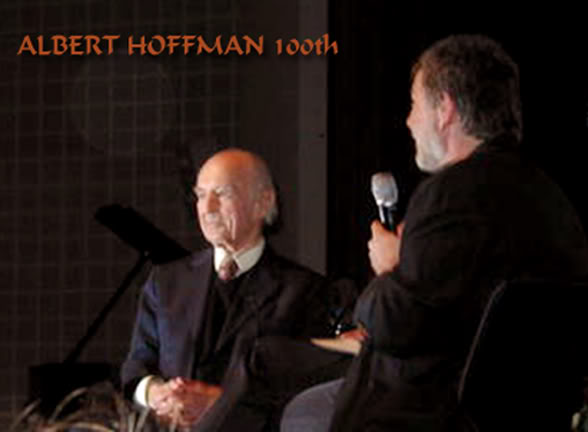

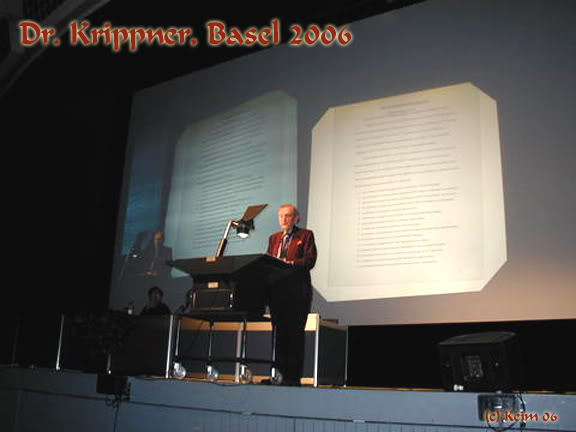

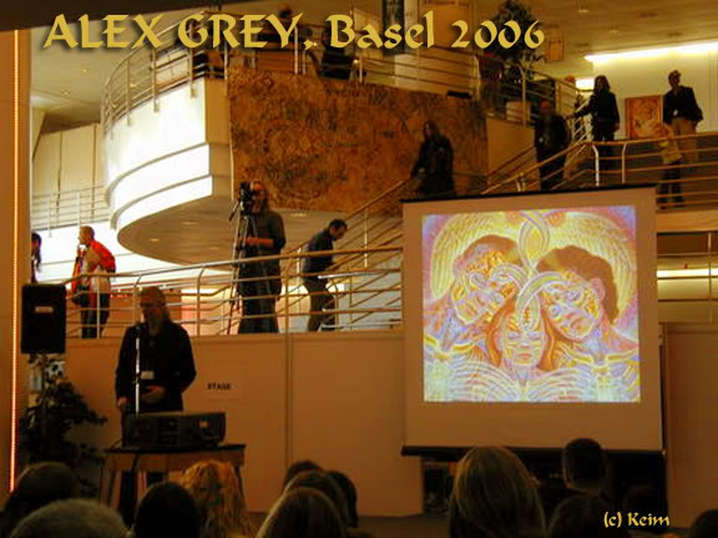

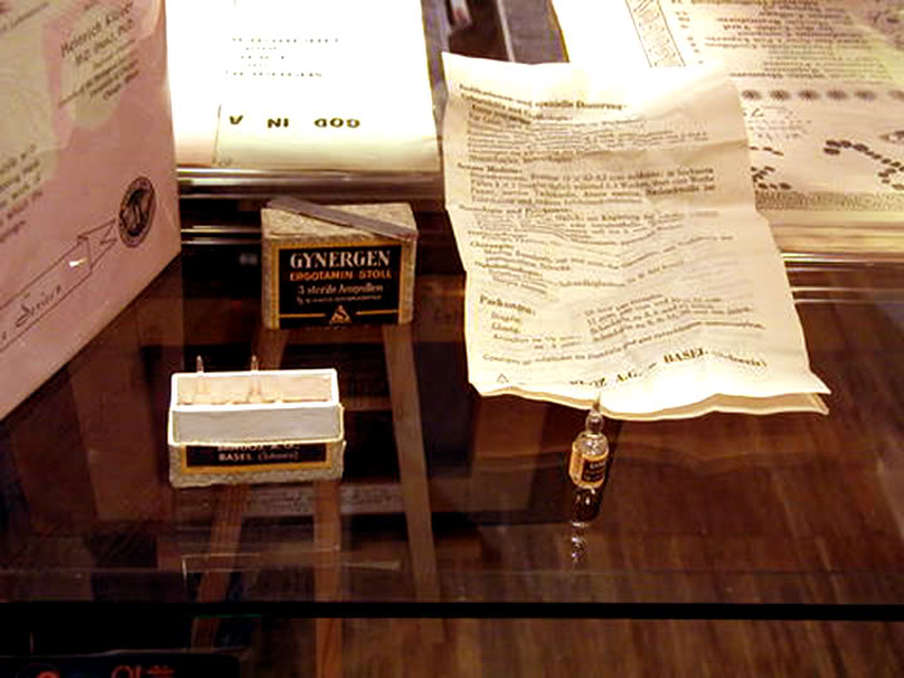

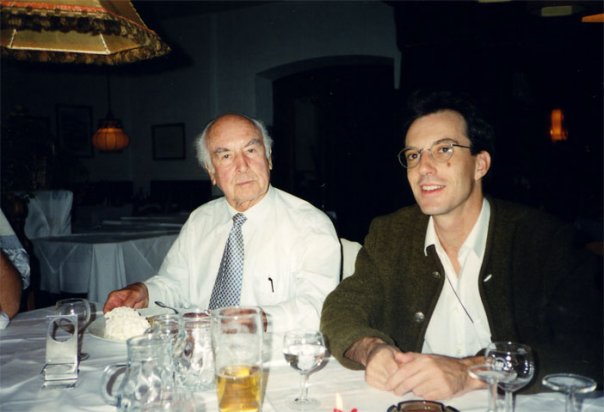

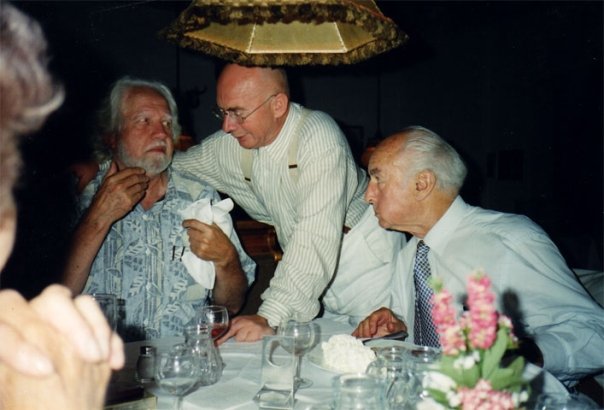

“Blue Elf Magick”: Hyperdelic animation of digital fine art and pix from Albert Hoffman 100th B-day party, Basel, Switzerland. Io collabo with electronic artist Philip Wood, France.

Flash Animations, Random Generator.

Music: Plastic Ono Band, “Do the Oz”.

ANIMATION OF IO ART: DO THE OZ

click here:

http://www.sign69.com/medialounge/space721.html

“Blue Elf Magick”: Hyperdelic animation of digital fine art and pix from Albert Hoffman 100th B-day party, Basel, Switzerland. Io collabo with electronic artist Philip Wood, France.

Flash Animations, Random Generator.

Music: Plastic Ono Band, “Do the Oz”.

Hunter Thompson wrote, "History is hard to know, because of all the hired bullshit, but even without being sure of 'history' it seems entirely reasonable to think that every now and then the energy of a whole generation comes to a head in a long fine flash, for reasons that nobody really understands at the time—and which never explain, in retrospect, what actually happened."

This they tell, and whether it happened so or not I do not know;

but if you think about it, you can see that it is true. --Black Elk

This they tell, and whether it happened so or not I do not know;

but if you think about it, you can see that it is true. --Black Elk

DFA by Iona Miller

co·gno·scen·tiˌkänyōˈSHentē,ˌkägnə-/nounplural noun: cognoscenti

1. people who are considered to be especially well informed about a particular subject.

A person with superior, usually specialized knowledge or highly refined taste; a connoisseur.

"Serenely let us move to distant places

And let no sentiments of home detain us

The Cosmic Spirit seeks not to restrain us

But lifts us stage by stage to wider spaces."

--Hesse, The Glass Bead Game

1. people who are considered to be especially well informed about a particular subject.

A person with superior, usually specialized knowledge or highly refined taste; a connoisseur.

"Serenely let us move to distant places

And let no sentiments of home detain us

The Cosmic Spirit seeks not to restrain us

But lifts us stage by stage to wider spaces."

--Hesse, The Glass Bead Game

Supersonic Hyperdelic

We're All Stars Now in the Dope Show

BEL > PM&E > HF/RH/Mondo 2000 > NonLinearCircle > Forum Alpbach

The Harmonic Convergence of

Psychedelics, Culture, Science & Technology

Embodied & Disembodied Identities

The Harmonic Convergence of

Psychedelics, Culture, Science & Technology

Embodied & Disembodied Identities

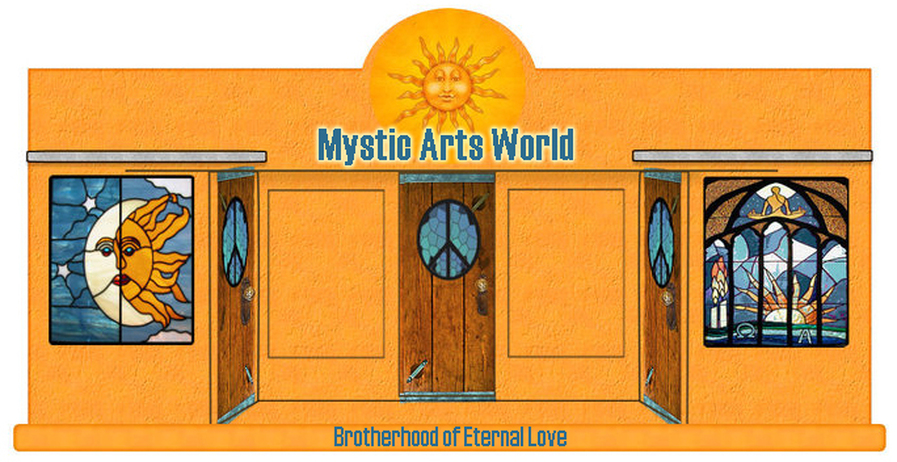

Brotherhood of Eternal Love

Peace, Love & Harmony with Nature

(Dodge City, Laguna Beach, Haight Ashbury, Maui, Global Network)

http://belhistory.weebly.com/index.html

1966-1972: From its founding in 1966, the BROTHERHOOD OF ETERNAL LOVE (BEL) has been pioneering and shaping society. They fueled the zeitgeist with synchronicity and the seeds of change. Jung said that “Synchronicity reveals the meaningful connections between the subjective and objective world.”

The story of the Brotherhood is more concerned with psychic forces -- archetypal, philosophical, and cosmic -- than it is with the historical and emotional lives of the characters that weave in and out of it. They did, however, embody a Holy Moment, a slice of space-time that superseded reality. They had the Gaze of those who pierced through the illusions of ordinary life to marvel at the deep archetypal forces that shape reality.

The Brotherhood became agents of mass transformation. But, "seeing everything" either leads into enlightenment or the deeper darkness of disillusionment. At some point, the vision becomes obsession and turns cloudy. The irrational depths of the soul are undeniable. The ever-burning energy of human instinct transmutes into creative power. The feedback of 20/20 hindsight shows that in the worship of their own creation, perhaps they misunderstood the symbol for the thing. Even when we see Reality, we may be unable to help the situation. The meaning lies not in abstract spirituality but in the [re]sacralization of earthly life, not the nightmares of history.

As mercurial tricksters and shamanic sorcerers, they helped expose society's entrenched hypocrisy through a rejection of obsolete values -- the consensual trance of traditional morality. In tearing the veil from the 3rd eye of millions, they revealed the psychedelic heart of creativity that transcends language and conceptualization.

But the mystic eye and the evil eye are the same organ - bent on different ends. The power to imagine still shapes the future. That visionary power is what makes us human. The Brotherhood story is bigger than than they are -- than the narratives of each individual life. It galvanized a movement. Today's Brothers are glad to have survived their adventures, whether it was real or only a dream lived aloud. Sometimes even a whole lifetime cannot reveal the whole truth. Their secrets remained concealed because they are experiential -- initiatory.

Joseph Campbell said, "What we call monsters can be experienced as sublime. They represent powers too vast for the normal forms of life to contain them. . .Meanwhile, you’re climbing, until suddenly you break past a screen and an expanse of horizon opens out, and somehow, with this diminishment of your own ego, your consciousness expands to an experience of the sublime."

Griggs and his buddies migrated from Anaheim, California to bucolic Modjeska Canyon, where they formed a pastoral church centered around hallucinogens. With entrepreneurial spirit, they developed an illicit drug business. Needing a low-key hideout in Laguna Beach, they moved to Woodland Drive, an out-of-the-way collection of cheap-rental cottages and shacks. Later, it was called "Dodge City". Then they opened an art gallery and head shop called Mystic Arts World on South Coast Highway.

This is one epic Dope Opera, full of psychedelic surfers entangled in lots of magic seaweed. Timothy Leary was their resident Godfather for two years of intense, unstructured brainstorming, both in Laguna and at the Idyllwild ranch. BEL romanticized the American Outlaw and themselves -- as brash streetwise outsiders, righteous guerrilla dealers, and freedom fighters, but not criminals. They made those 60s albums and concerts sound even better. The counterculture burst into technicolor bloom, reflecting deep mysteries in new hues -- especially orange sunshine.

Branding Bravado

Everybody and their brother seems to think they were associated, but the original BEL crew was actually quite small with roots in Junior High and High School in Anaheim. They were never a "motorcycle gang", despite that characterization. They were destined to become a legend in their own time, by selling celestial dreams and oceanic communion. The story of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love is a paradox of the '60s Southern California counterculture and an electrified metaphor describing the rise and fall of the entire phenomenon.

The saga of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love is a bizarre mélange of evangelical, starry-eyed hippie dealers, mystic alchemists, and fast-money bankers. Federal investigators described them as a "hippie Mafia" of approximately seven hundred fifty people that allegedly grossed $200,000,000. But the Brotherhood's secret

network of smugglers lived by a code different from that associated with organized crime. They were fired with idealism, committed to changing the world by disseminating large quantities of psychedelics. At least that's how it was at the beginning …. (Acid Dreams)

There's no soft-pedaling it -- the Brothers were drug distributors and smugglers who seized the magic moment of great instability and decay and provided a dynamic and very personal rebirth experience. In an era that deeply questioned the nature of reality, their history reads like a movie treatment, complete with hair-raising scenes of international smuggling in Afghanistan, near-arrests and miraculous escapes, surfing on acid, psychic visions, UFOs, agonies, ecstasies, and, of course, Leary with his bizarre escapades. Other like-minded groups formed, but the Brotherhood had a starring role with ambitious participation, amplified by Leary's financial and alchemical connections, patronage and payoffs.

BEL became a daring group of enormously successful underground drug manufacturers and dealers in LSD, pot, and hashish in the late ’60s to early ’70s. But the fact is that the brilliant glimpse of a living cosmos did pour through for a while, and it resulted in an unprecedented vision of a different world. One could debate forever the question of how much of what the drug did for us was contingent on the peculiar conditions of that time. The opening, however, was real. History can be funny that way.

Tuned in to the mystic arts yet aggressively pragmatic, the BEL believed they could transform the world by getting enough acid out on the underground market. They had already hit the JackPot with their grassroots network. Always seeking a utopian escape, some of BEL's members fled to Maui -- their 'Rainbow Island' -- where these transplanted pot smugglers turned to big-wave surfing, created Maui Waui, and appeared in their film Rainbow Bridge with Jimi Hendrix. A few returned to Santa Cruz and widely-dispersed Brotherhood properties within a short time.

Best Friends & Worst Enemies

The tightly-knit community went from zeros to heroes to the FBI's Most Wanted. The Brotherhood alchemists turned ergot mold into the gold of Orange Sunshine. Those who weren't caught individually or in the Operation BEL sweep went into hiding underground or abroad. The Brothers who had been best friends could also be worst enemies. Some brothers maintained the code of silence when faced with incarceration and even betrayal.

Tim Scully first met William "Billy" Mellon Hitchcock, grandson of William Larimer Mellon and great-great-grandson of Thomas Mellon, through Owsley in April 1967. They became friends and Billy loaned Scully $12,000 for the second Denver lab in 1968. The product from the lab was distributed by the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. Like Nick Sand, Scully was connected with the Brotherhood via Billy Hitchcock and Tim Leary.

In December 1968 Nick Sand (through an intermediary) purchased a farmhouse in Windsor, California where he and Tim Scully set up a large LSD lab. Tim Scully and Nick Sand (another psychedelic chemist) produced over 3.6 million tablets (300 micrograms each) of LSD they dubbed "Orange Sunshine" by the summer of 1969. In May 1969 Tim Scully was arrested in California for the 1968 Denver lab. The search was eventually ruled illegal, but Scully decided to retire from clandestine chemistry and pursue electronic design instead.

In 1972 the BEL alchemist, Nick Sand was prosecuted along with several members of the Brotherhood for the manufacturing of LSD. They had been the focus of a lengthy investigation by federal narcotics agents in the early 1970s. In early 1973 Billy Hitchcock was threatened with 24 years in prison for tax evasion if he didn't help the government convict the prime movers of the LSD cartel.

Billy provided evidence and testified against Tim Scully and Nick Sand and they were both indicted in April 1973. In 1976 Sand was found guilty partially due to the testimony of Billy Hitchcock and other "snitches" and was sentenced to 15 years in a federal penitentiary. Released on bail, he went underground in 1976 and remained a fugitive from federal agents for two decades.

One Drug Ring to Bind Them All

Core BEL brother, Glen Lynd turned state's evidence, revealing the entire BEL enterprise to the Feds for immunity from prosecution after Operation BEL. Patron Billy Hitchcock and even Leary turned snitch for a softer landing. In a stark reality check, middle-man Ronald Stark snitched for immunity on tax evasion and money laundering linked to Operation Julie in Britain. Some bad deals went down among the brothers themselves. The center could not hold.

One one level this is a true crime story: the evolution of a hippie drug smuggling operation and the cops who eventually took it down. But it's also a larger than life story about people who used highly illegal and unconventional ways to, in their point of view, bring peace on earth. Though many have tried, you cannot demystify the story of the Brotherhood, whose saga continues as a Peace Organization.

Silent Swagger

Some brothers don't wish to speak about any of it; others do. Some things are better left unsaid and "that was then and this is now". Some brothers still carry serious resentments and old gripes. In this dog eat dogma group, every dog has its day, every Brother has his say. Like blind men examining an elephant, many books, articles and videos describe different aspects of the Brotherhood, each with its own emphasis and spin. But all get mixed reviews for accuracy, even though they tried to interview other players who remain anonymous or silent.

We all tend to distill our experiences down into narratives we repeat almost verbatim. The best accounts are those by the brothers themselves, as reporters tell facts but fail to capture much of the flavor and fervor of the times. Despite its drug history, BEL remains what it essentially always was -- an activist spiritual organization, not just a pipedream, nebulous organization, or notorious legend. Eventually the Cold War nexus of institutions and ideas collapsed under their own weight. The process continues.

BEL survivors include Veterans, Ministers, Addiction Counselors, Healers, Artists, and Lamas. The core is still more interested in spirituality and helping fellow travelers on their life journey than in chasing the dollar, the Life-Spirit-Drug. If ministry is about touching peoples' lives, the BEL reached inside and rototilled their brains.

This is their story, and it is still unfolding, so check back as our archive grows. This connection has not been fully explored yet. Today's BEL is a social activist peace organization supporting veterans, health, and organic food choices for children, musical and community events. It's a conspirituality. The Brotherhood is still pushing Peace & Love and riding that cultural wave. Join the Revival. Show Us Your Peace Sign.

Peace, Love & Harmony with Nature

(Dodge City, Laguna Beach, Haight Ashbury, Maui, Global Network)

http://belhistory.weebly.com/index.html

1966-1972: From its founding in 1966, the BROTHERHOOD OF ETERNAL LOVE (BEL) has been pioneering and shaping society. They fueled the zeitgeist with synchronicity and the seeds of change. Jung said that “Synchronicity reveals the meaningful connections between the subjective and objective world.”

The story of the Brotherhood is more concerned with psychic forces -- archetypal, philosophical, and cosmic -- than it is with the historical and emotional lives of the characters that weave in and out of it. They did, however, embody a Holy Moment, a slice of space-time that superseded reality. They had the Gaze of those who pierced through the illusions of ordinary life to marvel at the deep archetypal forces that shape reality.

The Brotherhood became agents of mass transformation. But, "seeing everything" either leads into enlightenment or the deeper darkness of disillusionment. At some point, the vision becomes obsession and turns cloudy. The irrational depths of the soul are undeniable. The ever-burning energy of human instinct transmutes into creative power. The feedback of 20/20 hindsight shows that in the worship of their own creation, perhaps they misunderstood the symbol for the thing. Even when we see Reality, we may be unable to help the situation. The meaning lies not in abstract spirituality but in the [re]sacralization of earthly life, not the nightmares of history.

As mercurial tricksters and shamanic sorcerers, they helped expose society's entrenched hypocrisy through a rejection of obsolete values -- the consensual trance of traditional morality. In tearing the veil from the 3rd eye of millions, they revealed the psychedelic heart of creativity that transcends language and conceptualization.

But the mystic eye and the evil eye are the same organ - bent on different ends. The power to imagine still shapes the future. That visionary power is what makes us human. The Brotherhood story is bigger than than they are -- than the narratives of each individual life. It galvanized a movement. Today's Brothers are glad to have survived their adventures, whether it was real or only a dream lived aloud. Sometimes even a whole lifetime cannot reveal the whole truth. Their secrets remained concealed because they are experiential -- initiatory.

Joseph Campbell said, "What we call monsters can be experienced as sublime. They represent powers too vast for the normal forms of life to contain them. . .Meanwhile, you’re climbing, until suddenly you break past a screen and an expanse of horizon opens out, and somehow, with this diminishment of your own ego, your consciousness expands to an experience of the sublime."

Griggs and his buddies migrated from Anaheim, California to bucolic Modjeska Canyon, where they formed a pastoral church centered around hallucinogens. With entrepreneurial spirit, they developed an illicit drug business. Needing a low-key hideout in Laguna Beach, they moved to Woodland Drive, an out-of-the-way collection of cheap-rental cottages and shacks. Later, it was called "Dodge City". Then they opened an art gallery and head shop called Mystic Arts World on South Coast Highway.

This is one epic Dope Opera, full of psychedelic surfers entangled in lots of magic seaweed. Timothy Leary was their resident Godfather for two years of intense, unstructured brainstorming, both in Laguna and at the Idyllwild ranch. BEL romanticized the American Outlaw and themselves -- as brash streetwise outsiders, righteous guerrilla dealers, and freedom fighters, but not criminals. They made those 60s albums and concerts sound even better. The counterculture burst into technicolor bloom, reflecting deep mysteries in new hues -- especially orange sunshine.

Branding Bravado

Everybody and their brother seems to think they were associated, but the original BEL crew was actually quite small with roots in Junior High and High School in Anaheim. They were never a "motorcycle gang", despite that characterization. They were destined to become a legend in their own time, by selling celestial dreams and oceanic communion. The story of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love is a paradox of the '60s Southern California counterculture and an electrified metaphor describing the rise and fall of the entire phenomenon.

The saga of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love is a bizarre mélange of evangelical, starry-eyed hippie dealers, mystic alchemists, and fast-money bankers. Federal investigators described them as a "hippie Mafia" of approximately seven hundred fifty people that allegedly grossed $200,000,000. But the Brotherhood's secret

network of smugglers lived by a code different from that associated with organized crime. They were fired with idealism, committed to changing the world by disseminating large quantities of psychedelics. At least that's how it was at the beginning …. (Acid Dreams)

There's no soft-pedaling it -- the Brothers were drug distributors and smugglers who seized the magic moment of great instability and decay and provided a dynamic and very personal rebirth experience. In an era that deeply questioned the nature of reality, their history reads like a movie treatment, complete with hair-raising scenes of international smuggling in Afghanistan, near-arrests and miraculous escapes, surfing on acid, psychic visions, UFOs, agonies, ecstasies, and, of course, Leary with his bizarre escapades. Other like-minded groups formed, but the Brotherhood had a starring role with ambitious participation, amplified by Leary's financial and alchemical connections, patronage and payoffs.

BEL became a daring group of enormously successful underground drug manufacturers and dealers in LSD, pot, and hashish in the late ’60s to early ’70s. But the fact is that the brilliant glimpse of a living cosmos did pour through for a while, and it resulted in an unprecedented vision of a different world. One could debate forever the question of how much of what the drug did for us was contingent on the peculiar conditions of that time. The opening, however, was real. History can be funny that way.

Tuned in to the mystic arts yet aggressively pragmatic, the BEL believed they could transform the world by getting enough acid out on the underground market. They had already hit the JackPot with their grassroots network. Always seeking a utopian escape, some of BEL's members fled to Maui -- their 'Rainbow Island' -- where these transplanted pot smugglers turned to big-wave surfing, created Maui Waui, and appeared in their film Rainbow Bridge with Jimi Hendrix. A few returned to Santa Cruz and widely-dispersed Brotherhood properties within a short time.

Best Friends & Worst Enemies

The tightly-knit community went from zeros to heroes to the FBI's Most Wanted. The Brotherhood alchemists turned ergot mold into the gold of Orange Sunshine. Those who weren't caught individually or in the Operation BEL sweep went into hiding underground or abroad. The Brothers who had been best friends could also be worst enemies. Some brothers maintained the code of silence when faced with incarceration and even betrayal.

Tim Scully first met William "Billy" Mellon Hitchcock, grandson of William Larimer Mellon and great-great-grandson of Thomas Mellon, through Owsley in April 1967. They became friends and Billy loaned Scully $12,000 for the second Denver lab in 1968. The product from the lab was distributed by the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. Like Nick Sand, Scully was connected with the Brotherhood via Billy Hitchcock and Tim Leary.

In December 1968 Nick Sand (through an intermediary) purchased a farmhouse in Windsor, California where he and Tim Scully set up a large LSD lab. Tim Scully and Nick Sand (another psychedelic chemist) produced over 3.6 million tablets (300 micrograms each) of LSD they dubbed "Orange Sunshine" by the summer of 1969. In May 1969 Tim Scully was arrested in California for the 1968 Denver lab. The search was eventually ruled illegal, but Scully decided to retire from clandestine chemistry and pursue electronic design instead.

In 1972 the BEL alchemist, Nick Sand was prosecuted along with several members of the Brotherhood for the manufacturing of LSD. They had been the focus of a lengthy investigation by federal narcotics agents in the early 1970s. In early 1973 Billy Hitchcock was threatened with 24 years in prison for tax evasion if he didn't help the government convict the prime movers of the LSD cartel.

Billy provided evidence and testified against Tim Scully and Nick Sand and they were both indicted in April 1973. In 1976 Sand was found guilty partially due to the testimony of Billy Hitchcock and other "snitches" and was sentenced to 15 years in a federal penitentiary. Released on bail, he went underground in 1976 and remained a fugitive from federal agents for two decades.

One Drug Ring to Bind Them All

Core BEL brother, Glen Lynd turned state's evidence, revealing the entire BEL enterprise to the Feds for immunity from prosecution after Operation BEL. Patron Billy Hitchcock and even Leary turned snitch for a softer landing. In a stark reality check, middle-man Ronald Stark snitched for immunity on tax evasion and money laundering linked to Operation Julie in Britain. Some bad deals went down among the brothers themselves. The center could not hold.

One one level this is a true crime story: the evolution of a hippie drug smuggling operation and the cops who eventually took it down. But it's also a larger than life story about people who used highly illegal and unconventional ways to, in their point of view, bring peace on earth. Though many have tried, you cannot demystify the story of the Brotherhood, whose saga continues as a Peace Organization.

Silent Swagger

Some brothers don't wish to speak about any of it; others do. Some things are better left unsaid and "that was then and this is now". Some brothers still carry serious resentments and old gripes. In this dog eat dogma group, every dog has its day, every Brother has his say. Like blind men examining an elephant, many books, articles and videos describe different aspects of the Brotherhood, each with its own emphasis and spin. But all get mixed reviews for accuracy, even though they tried to interview other players who remain anonymous or silent.

We all tend to distill our experiences down into narratives we repeat almost verbatim. The best accounts are those by the brothers themselves, as reporters tell facts but fail to capture much of the flavor and fervor of the times. Despite its drug history, BEL remains what it essentially always was -- an activist spiritual organization, not just a pipedream, nebulous organization, or notorious legend. Eventually the Cold War nexus of institutions and ideas collapsed under their own weight. The process continues.

BEL survivors include Veterans, Ministers, Addiction Counselors, Healers, Artists, and Lamas. The core is still more interested in spirituality and helping fellow travelers on their life journey than in chasing the dollar, the Life-Spirit-Drug. If ministry is about touching peoples' lives, the BEL reached inside and rototilled their brains.

This is their story, and it is still unfolding, so check back as our archive grows. This connection has not been fully explored yet. Today's BEL is a social activist peace organization supporting veterans, health, and organic food choices for children, musical and community events. It's a conspirituality. The Brotherhood is still pushing Peace & Love and riding that cultural wave. Join the Revival. Show Us Your Peace Sign.

The dope dealer is selling you the celestial dream. He is very different from any other merchant because the commodity he is peddling is freedom and joy. In the years to come the television dramas and movies will make a big thing of the dope dealer of the sixties. He is going to be the Robin Hood, spiritual guerrilla, mysterious agent - who will take the place of the cowboy hero or the cops and robbers hero.' (Timothy Leary, 'Dope Dealers - New Robin Hood', 1967)

ORANGE CRUSH

They Lived in the Sun & Dealt in the Shade

Tim Leary was just selling ideas, not drugs. But his Brothers sure were.

Grassroots Network

Mostly, the hippies of the 1960s are remembered for their peaceful ways, for preaching 'Peace and Love'. In those days, parts of Orange County still looked like a vintage wooden fruitbox label. But, some of those visionaries foresaw the future and banded into what High Times and Rolling Stone dubbed a 'hippie mafia'. They were more pro-active than mere protesters. They launched a grassroots crusade against the mental inquisition of consumerism and conformity. Youth culture made a bigger quake than the San Andreas faultline before ultimately becoming commercialized itself into an over-the-counterculture.

The hippies were a social phenomenon which spurned materialism for their new tribal religion. But the brothers who grew up in the shadow of Disneyland still made untold millions, whether in a willing or inadvertent league with CIA and other black marketeers. Most likely they didn't realize it at the time. They were convinced this would change the world for the better.

Though BEL virtually cornered the acid market, they were never motivated by monopoly or "power". But the situation had them oscillating rapidly between everyday ego inflations and synthetic ego-death. Jung called ego-inflation a potential pitfall—amplifying the shadow of anyone practicing a “spiritual path.” They say without the prerequisite humor, honesty and humility, the danger only increases as one’s practice advances.

The identification with the collective psyche is acceptance of inflation, but now exalted into a system of great truths. Temporary ego death is an experience that is said to reveal the illusory aspect of the ego, but it can also feed an essentially bipolar cycle. Clearly, it is not the ego or self which is annihilated in ego death. Neither the ego of depth psychology nor the actual self, specifically the self-identity dissolves - only the belief boundaries we construct of past experiences and identification. From the perspective of unity, there is no such thing as dying, nor of being reborn. There is no such thing as ego death, and no such thing as enlightenment either, since you are already the unity. Transcendent experience goes beyond identifications structured by a particular self-representation.

Over the Rainbow

We now know you can't solve such problems with a pill. Spirituality is linked to the "oceanic" feeling of limitlessness. The sensation of an indissoluble bond is a deeply meaningful connection with the external world in its integral form. This feeling is an entirely subjective fact, not an article of faith. The oceanic experience is usually brief and completely unexpected. It is being at one with the entire universe, and of feeling a deep meaning and purpose to every part of existence.

This numinous experience is often accompanied by feelings of compassion and love for all beings. -- sacred participatory consciousness. But it may just be a momentary glimpse, a felt sense of what an integrated state would feel like. The universe looks very different seen from the inside out as pure consciousness apprehending itself. The holistic shift reveals that matter, energy, biology and consciousness are all inter-connected in a coherent sympathetic resonance.

If such behavior seems outrageous, remember we all grew up thinking we were under the constant threat of nuclear annihilation, or personal annihilation in the Wars -- overseas, or the drug war at home. The true war is a celebration of markets. Organic markets, carefully styled "black" by the professionals, spring up everywhere. The truer currencies emerge among people. The real dope may be the perpetuation of 'movements' -- the "you done it" genre. Everyone knew that in any scenario California was a hard target so there seemed little to lose.

Technology of the Sacred

LSD was the drug in "Sex, Drugs & Rock n Roll", the 'atom bomb of consciousness'. It was a catalyst for the personal and collective unconscious, amplifying whatever was there, positive or negative, and opening alien dimensions. Neither psychiatry nor religion has come to terms with the nature of mystic experiences. Acid had a profound creative influence despite the tie-dyed tipi-dwelling idealism.

When perception changes, what we construe to be reality changes. LSD reveals the psychoactive root of phenomenology, archetypes, symbols, and myth. It was a Eureka-experience for many. Acid became the Universal Solvent, the true Philosopher's Stone. This gift of the Mothercorn, ergot, sparked an archaic revival unequalled since the Eleusinian Mysteries. Hesiod wrote of Elysion: the island of the happy dead. We might say, 'the Grateful Dead'.

Researchers began devising maps of consciousness for the Far Off Lands. Stan Grof and Charles Tart cataloged a range of evolutionary stages recapitulated in mystical, mythological and psychobiological experiences and identifications from the species, to cellular, to quantum levels. Acid also was an antidote to watching the body count from the Vietnam war on TV with dinner every night. The brothers sprinkled their Brain Seasoning like fairy dust. It changed the consciousness and social history of America in many ways. It put the collective culture through a revolutionary type of ego death and renewal. As Jung said, modern man was in search of soul, and many found it on the heroic journey within, coupled with various technologies of visionary culture.

No Stone Unturned

BEL alchemists, (Nick Sand, Tim Scully, and Ronald Stark with Kemp) came in tow with Timothy Leary via Billy Hitchcock. They gave new meaning to the "Joy of Cooking" -- synthesizing heaven. They approached it with a certain reverence and intentionality. Acid is overwhelming. It all depends on whether that is positive or negative. When it comes to making acid, "cleanliness is next to Godliness." The purer it is, the clearer the experience. The chemists and distributors strongly believed in their mission to raise human consciousness by providing a rainbow bridge to the inner world.

The brothers had a vertically integrated system from production to delivery. It was a "new" way of thinking with deep roots in the ancient Mystery religions of psychedelic spirituality. The Revolution in consciousness meant the extraordinary became ordinary. The collective mind glimpsed its psychedelic ancient/future. The transcendental self came out to play.

Acid was more than a party drug; it changed people in profound and meaningful ways. More than recreational, it was re-creational, embodying the mystery of spiritual rebirth. Even Leary suggested that many had already ingested enough acid to learn its lessons and should move on. Many people, shown this transformation, thought to themselves, "Now, how can I do this without drugs?" The typical claim was to have 'seen God'. Jung describes the transformative effects of even the drug-free mystical experience of the instant present Presence as follows:

The God-image is the symbolic expression of a particular psychic state, or Function, which is characterized by its absolute ascendancy over the will of the subject, this inspiration that transcends conscious understanding, has its source in an accumulation of energy in the unconscious. The accumulated libido activates images lying dormant in the collective unconscious, among them the God-image, that [archetypal] . . . imprint which from the beginning of time has been the collective expression of the most overwhelmingly powerful influences exerted on the conscious mind by unconscious concentrations of libido. --Carl Jung; Psychological Types; 243-44.

God, becomes‟ by an act of conscious differentiation from the unconscious dynamis, a separation of the ego as subject from God . . . as object. . . . But when the “breakthrough” abolishes this separation by cutting the ego off from the world, and the ego becomes identical with the unconscious dynamis, God disappears as an object and dwindles into a subject which is no longer distinguishable from the ego. In other words, the ego, as a late product of differentiation, is reunited with the dynamic All-oneness. --Carl Jung; Psychological Types; 255.

Underground Swell

The brothers will say they went from Zeroes to Heroes to Zeroes with the busts, and perhaps in the end back to countercultural Heroes as their legend assumes its historical aspect. America loves a good redemption story, and some brothers remain to testify to that, rather than against one another. They thought of themselves as spiritual warriors, the 'untouchable' star-crossed Robin Hoods of acid, more of an outlaw band than criminal ring. They awoke one day in Laguna in the middle of history. But there was a riptide toward the shadowy depths that inexorably pulled them under. This is the tale of surf rebels who morphed into multi-million dollar international drug smugglers who pushed peace and love as hard as their mind-manifesting products.

Storming heaven, "High Priest" Timothy Leary declared a de facto war on ordinary consciousness. LSD opened a door to the scientific study of mystical experience. Those with the experience consider it a deeply meaningful event. Orange Sunshine became a "double agent", a shot across the bow of the establishment that provoked the longest War in American history -- on drugs. Image-wise, this War was headquartered at Nixon's nearby retreat in San Clemente. Meanwhile in Laguna Beach, heads were exploding out of conformist patterns into uncharted realms. Operation BEL and Operation Julie were launched to squash the government-manufactured counterculture, once and for all.

Yet that alternative society, or what is left of it, claimed they were idealists whose true history was guarded as carefully as any state secret. The Brotherhood supplied LSD and marijuana as a sacred mission, believing in the righteousness of their profession. They had lived outside the law from their high school days. No one can grasp what they did without understanding the rise of LSD, the growth of the psychedelic movement and the heady, optimistic, revolutionary, energized days of the 1960s. But this is not so much a story of drugs as it is of life and death, and the highs and lows of the human spirit.

The Brotherhood existed, achieving many of the legendary things claimed on its behalf. It certainly generated millions of dollars, as a loosely networked drug ring. First, they hit the "jack-Pot". It was also fired with idealism, novelty-seeking, and adventurism. The French might call it bel esprit, a clever person who uses the mind creatively.

Utopiates

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love was one part of a much greater movement fascinated by the potential of LSD to improve the quality of mankind's life. The promising psychiatric tool became a potent new weapon in the hands of generals and spymasters -- the manipulators of populations. The research, both civilian and military, was widespread. Besides the smuggling drug ring, as in Tolkein's trilogy there was "one ring to bind them all" -- the indole ring, a shared related structure in LSD, psilocybin, and neurotransmitters. Compounds that contain an indole ring are called indoles. The amino acid tryptophan is an indole derivative and the precursor of the neurotransmitter serotonin.

Many believed that through the heightened perceptions and insights it produced, LSD could radically alter the direction of the human race by creating a golden pathway to the future. Utopianism is a 'hope-iate'. The dream united diverse individuals who fueled the creation of the psychedelic movement. Drugs in the 1960s no longer meant the drugging down of society. They were seen as a means to 'enlightenment', or at least being the sorcerer's apprentice for a brief time. Distribution became a cosmic conspiracy -- conspirituality. But it caused tremendous backlash. That mystic arts spirit has triumphed and survives today in compassionate treatment and medical marijuana which has eased the suffering of millions and the newly-rekindled "psychedelic science".

They Lived in the Sun & Dealt in the Shade

Tim Leary was just selling ideas, not drugs. But his Brothers sure were.

Grassroots Network

Mostly, the hippies of the 1960s are remembered for their peaceful ways, for preaching 'Peace and Love'. In those days, parts of Orange County still looked like a vintage wooden fruitbox label. But, some of those visionaries foresaw the future and banded into what High Times and Rolling Stone dubbed a 'hippie mafia'. They were more pro-active than mere protesters. They launched a grassroots crusade against the mental inquisition of consumerism and conformity. Youth culture made a bigger quake than the San Andreas faultline before ultimately becoming commercialized itself into an over-the-counterculture.

The hippies were a social phenomenon which spurned materialism for their new tribal religion. But the brothers who grew up in the shadow of Disneyland still made untold millions, whether in a willing or inadvertent league with CIA and other black marketeers. Most likely they didn't realize it at the time. They were convinced this would change the world for the better.

Though BEL virtually cornered the acid market, they were never motivated by monopoly or "power". But the situation had them oscillating rapidly between everyday ego inflations and synthetic ego-death. Jung called ego-inflation a potential pitfall—amplifying the shadow of anyone practicing a “spiritual path.” They say without the prerequisite humor, honesty and humility, the danger only increases as one’s practice advances.

The identification with the collective psyche is acceptance of inflation, but now exalted into a system of great truths. Temporary ego death is an experience that is said to reveal the illusory aspect of the ego, but it can also feed an essentially bipolar cycle. Clearly, it is not the ego or self which is annihilated in ego death. Neither the ego of depth psychology nor the actual self, specifically the self-identity dissolves - only the belief boundaries we construct of past experiences and identification. From the perspective of unity, there is no such thing as dying, nor of being reborn. There is no such thing as ego death, and no such thing as enlightenment either, since you are already the unity. Transcendent experience goes beyond identifications structured by a particular self-representation.

Over the Rainbow

We now know you can't solve such problems with a pill. Spirituality is linked to the "oceanic" feeling of limitlessness. The sensation of an indissoluble bond is a deeply meaningful connection with the external world in its integral form. This feeling is an entirely subjective fact, not an article of faith. The oceanic experience is usually brief and completely unexpected. It is being at one with the entire universe, and of feeling a deep meaning and purpose to every part of existence.

This numinous experience is often accompanied by feelings of compassion and love for all beings. -- sacred participatory consciousness. But it may just be a momentary glimpse, a felt sense of what an integrated state would feel like. The universe looks very different seen from the inside out as pure consciousness apprehending itself. The holistic shift reveals that matter, energy, biology and consciousness are all inter-connected in a coherent sympathetic resonance.

If such behavior seems outrageous, remember we all grew up thinking we were under the constant threat of nuclear annihilation, or personal annihilation in the Wars -- overseas, or the drug war at home. The true war is a celebration of markets. Organic markets, carefully styled "black" by the professionals, spring up everywhere. The truer currencies emerge among people. The real dope may be the perpetuation of 'movements' -- the "you done it" genre. Everyone knew that in any scenario California was a hard target so there seemed little to lose.

Technology of the Sacred

LSD was the drug in "Sex, Drugs & Rock n Roll", the 'atom bomb of consciousness'. It was a catalyst for the personal and collective unconscious, amplifying whatever was there, positive or negative, and opening alien dimensions. Neither psychiatry nor religion has come to terms with the nature of mystic experiences. Acid had a profound creative influence despite the tie-dyed tipi-dwelling idealism.

When perception changes, what we construe to be reality changes. LSD reveals the psychoactive root of phenomenology, archetypes, symbols, and myth. It was a Eureka-experience for many. Acid became the Universal Solvent, the true Philosopher's Stone. This gift of the Mothercorn, ergot, sparked an archaic revival unequalled since the Eleusinian Mysteries. Hesiod wrote of Elysion: the island of the happy dead. We might say, 'the Grateful Dead'.

Researchers began devising maps of consciousness for the Far Off Lands. Stan Grof and Charles Tart cataloged a range of evolutionary stages recapitulated in mystical, mythological and psychobiological experiences and identifications from the species, to cellular, to quantum levels. Acid also was an antidote to watching the body count from the Vietnam war on TV with dinner every night. The brothers sprinkled their Brain Seasoning like fairy dust. It changed the consciousness and social history of America in many ways. It put the collective culture through a revolutionary type of ego death and renewal. As Jung said, modern man was in search of soul, and many found it on the heroic journey within, coupled with various technologies of visionary culture.

No Stone Unturned

BEL alchemists, (Nick Sand, Tim Scully, and Ronald Stark with Kemp) came in tow with Timothy Leary via Billy Hitchcock. They gave new meaning to the "Joy of Cooking" -- synthesizing heaven. They approached it with a certain reverence and intentionality. Acid is overwhelming. It all depends on whether that is positive or negative. When it comes to making acid, "cleanliness is next to Godliness." The purer it is, the clearer the experience. The chemists and distributors strongly believed in their mission to raise human consciousness by providing a rainbow bridge to the inner world.

The brothers had a vertically integrated system from production to delivery. It was a "new" way of thinking with deep roots in the ancient Mystery religions of psychedelic spirituality. The Revolution in consciousness meant the extraordinary became ordinary. The collective mind glimpsed its psychedelic ancient/future. The transcendental self came out to play.

Acid was more than a party drug; it changed people in profound and meaningful ways. More than recreational, it was re-creational, embodying the mystery of spiritual rebirth. Even Leary suggested that many had already ingested enough acid to learn its lessons and should move on. Many people, shown this transformation, thought to themselves, "Now, how can I do this without drugs?" The typical claim was to have 'seen God'. Jung describes the transformative effects of even the drug-free mystical experience of the instant present Presence as follows:

The God-image is the symbolic expression of a particular psychic state, or Function, which is characterized by its absolute ascendancy over the will of the subject, this inspiration that transcends conscious understanding, has its source in an accumulation of energy in the unconscious. The accumulated libido activates images lying dormant in the collective unconscious, among them the God-image, that [archetypal] . . . imprint which from the beginning of time has been the collective expression of the most overwhelmingly powerful influences exerted on the conscious mind by unconscious concentrations of libido. --Carl Jung; Psychological Types; 243-44.

God, becomes‟ by an act of conscious differentiation from the unconscious dynamis, a separation of the ego as subject from God . . . as object. . . . But when the “breakthrough” abolishes this separation by cutting the ego off from the world, and the ego becomes identical with the unconscious dynamis, God disappears as an object and dwindles into a subject which is no longer distinguishable from the ego. In other words, the ego, as a late product of differentiation, is reunited with the dynamic All-oneness. --Carl Jung; Psychological Types; 255.

Underground Swell

The brothers will say they went from Zeroes to Heroes to Zeroes with the busts, and perhaps in the end back to countercultural Heroes as their legend assumes its historical aspect. America loves a good redemption story, and some brothers remain to testify to that, rather than against one another. They thought of themselves as spiritual warriors, the 'untouchable' star-crossed Robin Hoods of acid, more of an outlaw band than criminal ring. They awoke one day in Laguna in the middle of history. But there was a riptide toward the shadowy depths that inexorably pulled them under. This is the tale of surf rebels who morphed into multi-million dollar international drug smugglers who pushed peace and love as hard as their mind-manifesting products.

Storming heaven, "High Priest" Timothy Leary declared a de facto war on ordinary consciousness. LSD opened a door to the scientific study of mystical experience. Those with the experience consider it a deeply meaningful event. Orange Sunshine became a "double agent", a shot across the bow of the establishment that provoked the longest War in American history -- on drugs. Image-wise, this War was headquartered at Nixon's nearby retreat in San Clemente. Meanwhile in Laguna Beach, heads were exploding out of conformist patterns into uncharted realms. Operation BEL and Operation Julie were launched to squash the government-manufactured counterculture, once and for all.

Yet that alternative society, or what is left of it, claimed they were idealists whose true history was guarded as carefully as any state secret. The Brotherhood supplied LSD and marijuana as a sacred mission, believing in the righteousness of their profession. They had lived outside the law from their high school days. No one can grasp what they did without understanding the rise of LSD, the growth of the psychedelic movement and the heady, optimistic, revolutionary, energized days of the 1960s. But this is not so much a story of drugs as it is of life and death, and the highs and lows of the human spirit.

The Brotherhood existed, achieving many of the legendary things claimed on its behalf. It certainly generated millions of dollars, as a loosely networked drug ring. First, they hit the "jack-Pot". It was also fired with idealism, novelty-seeking, and adventurism. The French might call it bel esprit, a clever person who uses the mind creatively.

Utopiates

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love was one part of a much greater movement fascinated by the potential of LSD to improve the quality of mankind's life. The promising psychiatric tool became a potent new weapon in the hands of generals and spymasters -- the manipulators of populations. The research, both civilian and military, was widespread. Besides the smuggling drug ring, as in Tolkein's trilogy there was "one ring to bind them all" -- the indole ring, a shared related structure in LSD, psilocybin, and neurotransmitters. Compounds that contain an indole ring are called indoles. The amino acid tryptophan is an indole derivative and the precursor of the neurotransmitter serotonin.

Many believed that through the heightened perceptions and insights it produced, LSD could radically alter the direction of the human race by creating a golden pathway to the future. Utopianism is a 'hope-iate'. The dream united diverse individuals who fueled the creation of the psychedelic movement. Drugs in the 1960s no longer meant the drugging down of society. They were seen as a means to 'enlightenment', or at least being the sorcerer's apprentice for a brief time. Distribution became a cosmic conspiracy -- conspirituality. But it caused tremendous backlash. That mystic arts spirit has triumphed and survives today in compassionate treatment and medical marijuana which has eased the suffering of millions and the newly-rekindled "psychedelic science".

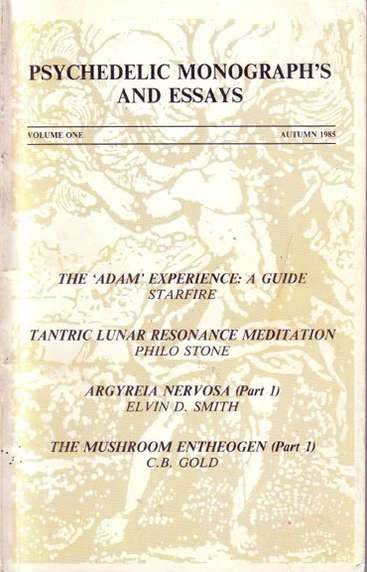

Psychedelic Monographs & Essays

Tom Lyttle, Editor, (Ft. Laurderdale)

http://tomlyttle.weebly.com/

Tom Lyttle, Editor, (Ft. Laurderdale)

http://tomlyttle.weebly.com/

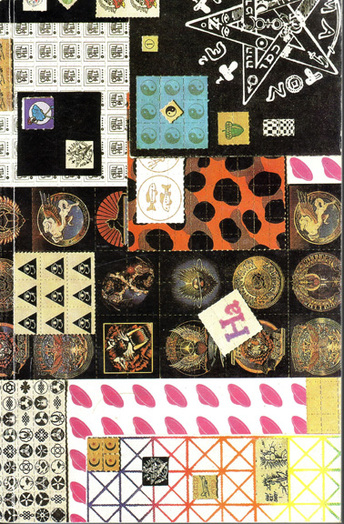

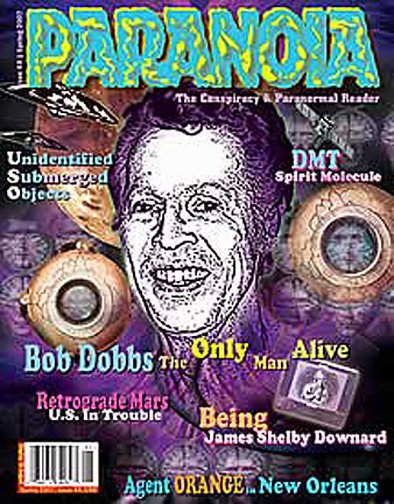

PM&E

Thomas Lyttle (b. 5-5-55 / d. 9-5-08) was Publisher and Editor of the kaleidoscopic journal PSYCHEDELIC MONOGRAPHS & ESSAYS, the books PSYCHEDELICS and PSYCHEDELICS REIMAGINED (Autonomedia). Later, he sold signed blotters of non-impregnated blotter art. His articles were published by Feral Press, Disinformation, High Times, Boing Boing, New Times, Paranoia, many scholarly journals and underground zines. His blotter art included signed editions by pop icons Albert Hofmann, Timothy Leary, Peter Fonda, Allan Ginsberg, John Lilly, Ken Kesey, Ram Dass, Ira Cohen, Laura Huxley, Annie Sprinkle, Robert Anton Wilson, Alex Grey, H.R. Giger, Laurence Gartel and other noted figures of the international underground. His insightful interviews included Peter Stafford, Peter Gorman, Dan Merkur, Dr. Rick Strassman, Robert Venosa (Heads), Alex Grey (High Times), Lisa Law (Heads) Jay Fikes, Paul Krassner, Clark Heinrich, and more.

ACID GREEN

Lyttle's works contributed to the 'acid greening' of the post-Postmodern cultural scene which has led back to serious psychedelic research. Psychedelics have been linked with non-ordinary perception or knowledge, healing, creativity and self-actualization. Modern studies are confirming the therapeutic value in psychedelic experience.

When it comes to accessing the psychedelic state, meditators think the psychonauts are missing something, while the psychonauts think the same about them. Brain synchronization technology is closing the gap with "electronic dope." Binaural beat signals drive the brain automatically into resonance with alpha and theta facilitating altered states. The organic relationship with one's ally may indeed be lacking. But resonance therapy can easily be part of a daily regime of self-care.

Psychedelic means 'mind expanding,' 'soul revealing,' or 'mind manifesting' and doesn't always refer to drug experience. It has to do with embodying the genius of human potential, with access and penetration of our unknown heights and depths. John Curtis Gowan codified these experiences in the 1970s and his work, Development of the Psychedelic Individual *, remains a valuable reference along with others (James, Maslow, Grof, Tart, Wilber). Collective 'ego death' may be a viable model for profound changes in the global cultural landscape. We need bigger stories and bigger solutions. For some, entheogens will remain both Universal Solvent and Panacea.

Thomas Lyttle was the publisher and editor of Psychedelic Monographs and Essays, a periodical that provided information to the counterculture at a time when mainstream publishing on the topic of illicit psychoactive drugs had slowed to a crawl. The first issue came out in the autumn of 1985, and the sixth and final issue appeared in 1993. PM&E evolved out of the newsletter the Psychozoic Press--An Informational Advisory and Communications Exchange Paper on Psychedelics, which first appeared in 1982. Editor Elvin D. Smith produced ten issues of the Psychozoic Press, and he continued to provide editorial input for PM&E until his death in 1988.

Following the conclusion of Lyttle's run as an editor and publisher, he created a "best of" compilation using selections from PM&E, titled Psychedelics: A Collection of the Most Exciting New Material on Psychedelic Drugs. Published by Barricade Books Inc. in 1994, Psychedelics saw wider distribution than PM&E had seen. The final book Lyttle edited was Psychedelics Reimagined, (Autonomedia) which contained writings by folks like Timothy Leary, Hakim Bey, Otto Snow, Iona Miller, Chris Bennett, Liz Rymland, John W. Allen, Jochen Gartz, and others.

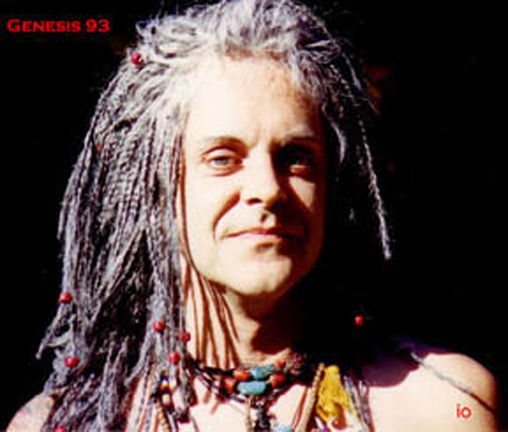

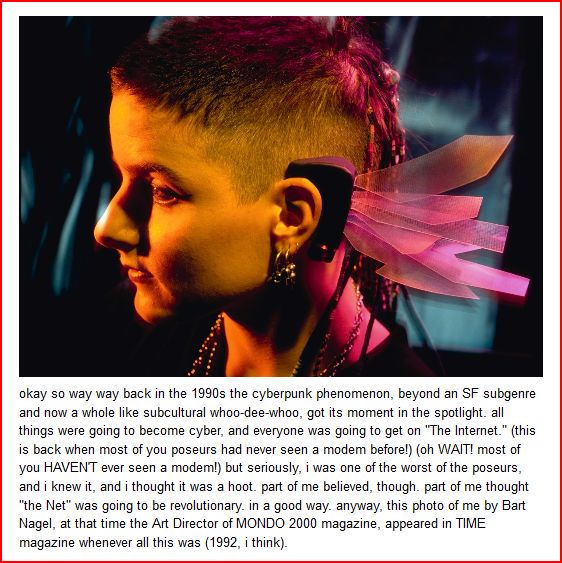

Genesis p-Orridge, Isis Oasis, 1993

We wanted to get together for our annual visit with editor Tom Lyttle of PM&E and decided on Isis Oasis in Geyserville. Tom invited his friends from the experimental triad group marriage Phoenix from Beverly Hills. Lyn Ehrnstein was the lawyer for Synanon, the pioneer heroin recovery program. Neo-pagan movement pioneers and The Church of All Worlds founders Tim [Otter-OZ-Oberon] and Morning Glory Zell also came for their 20th anniversary celebration. CAW was patterned after Heinlein’s ‘Stranger in a Strange Land’. Other CAW members included Anodea Judith, who wrote ‘Wheels of Life’ for Llewellyn on the chakras, her husband Richard, Sandra and Morgan Ware, CAW members there for the Eleusian Mysteries Ceremony. CAW member, Adam Walks Between Worlds, who wrote terrific articles on Jack Parsons and Robert Heinlein for Green Egg, meant to bring McKenna and Valle, but plans changed. Genesis p-Orridge was a sensational addition. This was the second time we failed to connect with McKenna, another being when we were at the MONDO 2000 house in Berkeley. We had his former girlfriend, the one from his butterfly book on Southeast Asia, with us. When we left, one of them was literally rolling on the floor, holding his head, exclaiming “I can’t believe it!”. Naturally, we had copious Mu tea.

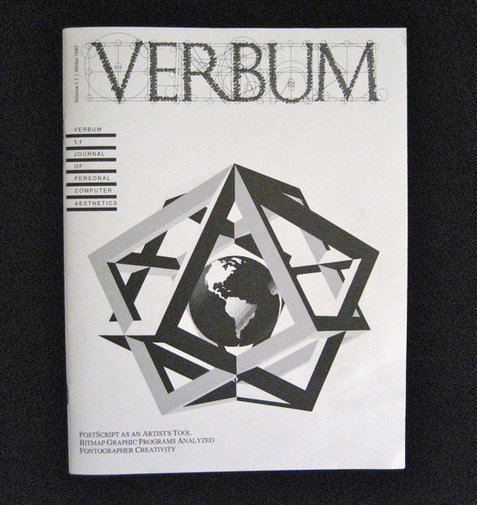

VERBUM Journal & Digital Be-In

Michael Gosney

Michael Gosney is a recognized new media publishing pioneer and entrepreneur, going back as far as 1986 with the launch of his quarterly Verbum Journal. One of the first completely desktop published magazines, and the first to showcase and instruct on the art of digital media, Verbum was a key player in the genesis of the new industry, with sponsors Adobe, Apple, Radius and others.

Michael was ahead of the curve again when in 1991 he created Verbum Interactive 1.0, a multimedia version of the magazine and the first true multimedia CD-ROM. Since that time, the firm has been involved in many pioneering publishing and multimedia projects, both proprietary, and for clients such as Apple Computer, Toshiba, Kodak and Microsoft.

Mr. Gosney was the creator of the culturally significant events: Digital Be-In (based on the Human Be-In on the 1960s) and the Paradox Conference, which we have played a role in over many years. He also gave birth to the Radio-V music channel which we built together from the ground up.

Michael has authored (or co-authored) a dozen books, including The Official Photo Cd Handbook, Multimedia Power Tools, Making Art on the MacIntosh II, and the Grey Book. Today, he is involved in eBook publishing and traditional book and music projects. He is also a driving force behind the electronic dance music venture, Cyberset Records.

http://bgamedia.com/about_michael.htm

Michael Gosney has been involved in innovative publishing ventures for over 15 years. In 1981, he founded Avant Books, a trade publishing house, publishing prestigious literary works such as Buddha by Nikos Kazantzakis and Clear Wind by Neeli Cherkovski, and non-fiction titles such as Deep Ecology, ed. by Michael Tobias, The Roots of Rastafari by Virginia Lee Jabobs, and The Life and Adventures of John Muir by James Mitchell Clarke.

Gosney launched The Word Shop in 1984, a book production service featuring one of the first commercial computer-phototypesetting systems in use on the West Coast. In 1985 he co-founded Microtrend, a computer book publisher/packager which developed publishing programs for firms such as IBM, Tandy, McGraw Hill and Mitchell Publishing.

In 1987 Gosney founded Verbum, Inc. with the publication of the Verbum Journal, the first magazine devoted to the creative applications of desktop media. Verbum was instrumental in the genesis of the desktop publishing field, and, through its coverage of digital animation, photography, music composition, video and interactive programming, was a catalyst for what became the multimedia field. In August of 1991 Verbum shipped Verbum Interactive, the nascent industry's first true multimedia product: a double CD-ROM featuring a pioneering interface design, stunning graphics, original music, animation and video. Sony, Macromedia, GTE and other firms participated in the development of Verbum Interactive, which inspired many of the early multimedia titles.

Between 1992 and 1996, Verbum produced leading instructional books for digital media professionals, including Multimedia Power Tools, the "bible" of the multimedia field with a CD-ROM dynamically linked to the book's contents, featuring step-by-step instruction. Other books included the Official Photo CD Handbook, in partnership with Kodak, and the Desktop Color Book. Once the market for CD-ROM was finally established, Verbum began development of its first consumer product in 1996, Peter Norton's PC Guru, a double CD-ROM published by MediaX in January 1998. Verbum is developing other proprietary products for publication on CD-ROM and the Internet. In January of 1998, Verbum launched Studio-V, a services division offering custom Internet and CD-ROM publication development.

Along with a circle of co-producers, Gosney produces the annual Digital Be-In in San Francisco, an influential gathering of new media pioneers now in its 10th year. In 1997 he launched the annual Paradox Conference on cyberspace, arcology and human evolution at Arcosanti, Arizona. He has been a frequent speaker at digital media industry events in the U.S., Japan, and South America since the mid-1980s. http://www.be-in.com/10/bios/gosney.html

Michael Gosney

Michael Gosney is a recognized new media publishing pioneer and entrepreneur, going back as far as 1986 with the launch of his quarterly Verbum Journal. One of the first completely desktop published magazines, and the first to showcase and instruct on the art of digital media, Verbum was a key player in the genesis of the new industry, with sponsors Adobe, Apple, Radius and others.

Michael was ahead of the curve again when in 1991 he created Verbum Interactive 1.0, a multimedia version of the magazine and the first true multimedia CD-ROM. Since that time, the firm has been involved in many pioneering publishing and multimedia projects, both proprietary, and for clients such as Apple Computer, Toshiba, Kodak and Microsoft.

Mr. Gosney was the creator of the culturally significant events: Digital Be-In (based on the Human Be-In on the 1960s) and the Paradox Conference, which we have played a role in over many years. He also gave birth to the Radio-V music channel which we built together from the ground up.

Michael has authored (or co-authored) a dozen books, including The Official Photo Cd Handbook, Multimedia Power Tools, Making Art on the MacIntosh II, and the Grey Book. Today, he is involved in eBook publishing and traditional book and music projects. He is also a driving force behind the electronic dance music venture, Cyberset Records.

http://bgamedia.com/about_michael.htm

Michael Gosney has been involved in innovative publishing ventures for over 15 years. In 1981, he founded Avant Books, a trade publishing house, publishing prestigious literary works such as Buddha by Nikos Kazantzakis and Clear Wind by Neeli Cherkovski, and non-fiction titles such as Deep Ecology, ed. by Michael Tobias, The Roots of Rastafari by Virginia Lee Jabobs, and The Life and Adventures of John Muir by James Mitchell Clarke.

Gosney launched The Word Shop in 1984, a book production service featuring one of the first commercial computer-phototypesetting systems in use on the West Coast. In 1985 he co-founded Microtrend, a computer book publisher/packager which developed publishing programs for firms such as IBM, Tandy, McGraw Hill and Mitchell Publishing.

In 1987 Gosney founded Verbum, Inc. with the publication of the Verbum Journal, the first magazine devoted to the creative applications of desktop media. Verbum was instrumental in the genesis of the desktop publishing field, and, through its coverage of digital animation, photography, music composition, video and interactive programming, was a catalyst for what became the multimedia field. In August of 1991 Verbum shipped Verbum Interactive, the nascent industry's first true multimedia product: a double CD-ROM featuring a pioneering interface design, stunning graphics, original music, animation and video. Sony, Macromedia, GTE and other firms participated in the development of Verbum Interactive, which inspired many of the early multimedia titles.

Between 1992 and 1996, Verbum produced leading instructional books for digital media professionals, including Multimedia Power Tools, the "bible" of the multimedia field with a CD-ROM dynamically linked to the book's contents, featuring step-by-step instruction. Other books included the Official Photo CD Handbook, in partnership with Kodak, and the Desktop Color Book. Once the market for CD-ROM was finally established, Verbum began development of its first consumer product in 1996, Peter Norton's PC Guru, a double CD-ROM published by MediaX in January 1998. Verbum is developing other proprietary products for publication on CD-ROM and the Internet. In January of 1998, Verbum launched Studio-V, a services division offering custom Internet and CD-ROM publication development.

Along with a circle of co-producers, Gosney produces the annual Digital Be-In in San Francisco, an influential gathering of new media pioneers now in its 10th year. In 1997 he launched the annual Paradox Conference on cyberspace, arcology and human evolution at Arcosanti, Arizona. He has been a frequent speaker at digital media industry events in the U.S., Japan, and South America since the mid-1980s. http://www.be-in.com/10/bios/gosney.html

The Digital Be-In is an ongoing San Francisco-based event that began with a mission to carry forth the ethos and values expressed at the 1960s' Human Be-In, and bring them into the world of multimedia and Internet technology. It served a role through the 1990s as a venue for the San Francisco Bay Area's community of new media pioneers to socialize and exchange ideas. Cyberculture became the focal point of the gatherings. However, producer Michael Gosney also brought in key figures from the Human Be-In such as Allen Cohen, Chet Helms and Timothy Leary to maintain the 60s influence, as well as 60s icons Ken Kesey, Ram Dass and Wavy Gravy. The most recent event (Digital Be-In 16: ECOCITY) was held 2008-04-28. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_Be-In

In the early years, it drew major companies as sponsors, such as Apple, Microsoft, Adobe Systems and Kodak, while at the same time staying an underground party. After 1997 and after the year 2000, the event started to show maturity. The production team organized socially conscious themes that began catching on with the Be-In attendees, to the point where the symposium for the 2006 theme, Planet Code, had as large an audience as the party that followed it.

Inspired by the 1967 Human Be-In, the first Digital Be-In was held on January 21, 1989 in San Francisco, as a party for Verbum magazine, an early digital art magazine. Verbum president, Michael Gosney, promoted digital media and early desktop publishing as a way to continue the countercultural ideas that were begun during the original Be-In and the Summer of Love, while underscoring the visionary and humanistic components of cyberculture.

Computer-industry people and underground artists came together at the first Digital Be-In to celebrate the emergent electronic art and design medium, entertained by a combination of music and visuals. At subsequent events, Gosney also involved co-founders of the Human Be-In, Allen Cohen, Chet Helms, Timothy Leary and John Perry Barlow.

Verbum held 10 consecutive Be-Ins during Macworld Conference & Expo every January until 1998. During the 3rd year, Allen Cohen showcased a hardcover volume of the entire run of the SF Oracle issues. In its 4th year, the event occurred on the 25th Anniversary of the Human Be-In. That 4th event, called the New Human Be-In, became the first public event. Although Wired Magazine editor Gary Wolf belittled the presence so-called smart drugs, he acknowledged that the New Human Be-In was one of the rare occasions that year where the Bay Area's community of "gadget-lovers and artists, programmers and entrepreneurs" gathered in person.

In 1995, the official name was shortened from Digital Art Be-In simply to Digital Be-In. Additionally that year, Verbum organized a Be-In in Tokyo. There they had a video tape message from Timothy Leary, a presentation on the links between the 1960s counterculture of the Bay Area and the personal computer revolution, a Digital Art Gallery, and the Digital Frontier included exhibits by avant garde multimedia publishers.

Through the 1990s, the Be-In went on to feature the development of new technology and digital art alongside immersive light shows. Projections combined original 1960s artists' analog work with video effects and 3D digital animation. In 1996, the 8th Be-In took its next step and started netcasting.

In 1997, Digital Be-In 9 matured with the introduction of a political theme, "Cultural Diversity in Cyberspace." Number 10 was themed "Human Rights in Cyberspace" and number 11 was "Body, Mind and Cyberspace." Then there was a break for the millennium. Number 12 resumed in 2002, under the theme "Media Revolution," number 13, "The Transparent Network" was in 2004 and number 14, "Planet Code," happened on Earth Day, April 22, 2006.

In the early years, it drew major companies as sponsors, such as Apple, Microsoft, Adobe Systems and Kodak, while at the same time staying an underground party. After 1997 and after the year 2000, the event started to show maturity. The production team organized socially conscious themes that began catching on with the Be-In attendees, to the point where the symposium for the 2006 theme, Planet Code, had as large an audience as the party that followed it.

Inspired by the 1967 Human Be-In, the first Digital Be-In was held on January 21, 1989 in San Francisco, as a party for Verbum magazine, an early digital art magazine. Verbum president, Michael Gosney, promoted digital media and early desktop publishing as a way to continue the countercultural ideas that were begun during the original Be-In and the Summer of Love, while underscoring the visionary and humanistic components of cyberculture.

Computer-industry people and underground artists came together at the first Digital Be-In to celebrate the emergent electronic art and design medium, entertained by a combination of music and visuals. At subsequent events, Gosney also involved co-founders of the Human Be-In, Allen Cohen, Chet Helms, Timothy Leary and John Perry Barlow.

Verbum held 10 consecutive Be-Ins during Macworld Conference & Expo every January until 1998. During the 3rd year, Allen Cohen showcased a hardcover volume of the entire run of the SF Oracle issues. In its 4th year, the event occurred on the 25th Anniversary of the Human Be-In. That 4th event, called the New Human Be-In, became the first public event. Although Wired Magazine editor Gary Wolf belittled the presence so-called smart drugs, he acknowledged that the New Human Be-In was one of the rare occasions that year where the Bay Area's community of "gadget-lovers and artists, programmers and entrepreneurs" gathered in person.

In 1995, the official name was shortened from Digital Art Be-In simply to Digital Be-In. Additionally that year, Verbum organized a Be-In in Tokyo. There they had a video tape message from Timothy Leary, a presentation on the links between the 1960s counterculture of the Bay Area and the personal computer revolution, a Digital Art Gallery, and the Digital Frontier included exhibits by avant garde multimedia publishers.

Through the 1990s, the Be-In went on to feature the development of new technology and digital art alongside immersive light shows. Projections combined original 1960s artists' analog work with video effects and 3D digital animation. In 1996, the 8th Be-In took its next step and started netcasting.

In 1997, Digital Be-In 9 matured with the introduction of a political theme, "Cultural Diversity in Cyberspace." Number 10 was themed "Human Rights in Cyberspace" and number 11 was "Body, Mind and Cyberspace." Then there was a break for the millennium. Number 12 resumed in 2002, under the theme "Media Revolution," number 13, "The Transparent Network" was in 2004 and number 14, "Planet Code," happened on Earth Day, April 22, 2006.

- Tune in, drop out. Rewired online journal.

- Be-In Digital. Atlantic Monthly article.

- Everybody must get stoned. Wired magazine article.

- The way we were. Wired magazine article.

- Be-In Website

- Digital Be-In History

- Live from the Digital Be-In. A report by Ken Kesey Intrepid Trips.

- Allen Cohen biography

- Turn on. Tune in. Take charge. Lawrence Hagerty's Be-In 12 speech.

- Be-In Now. Be-In 13 blog.

- Grokking the transparent network. Common Ground story.

- Notes from the Digital Be-In. Futuresalon blog entry.

- Planet Code Digital Be-In. Onevillage blog entry.

- Back from the Digital Be-In. Technologist Eric Magnuson's blog entry.

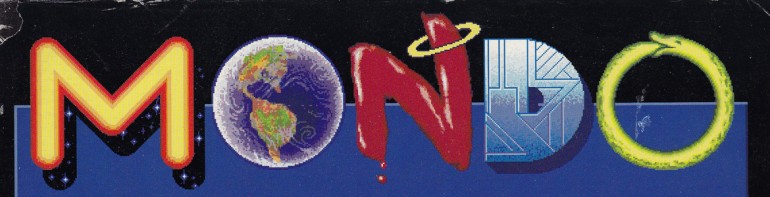

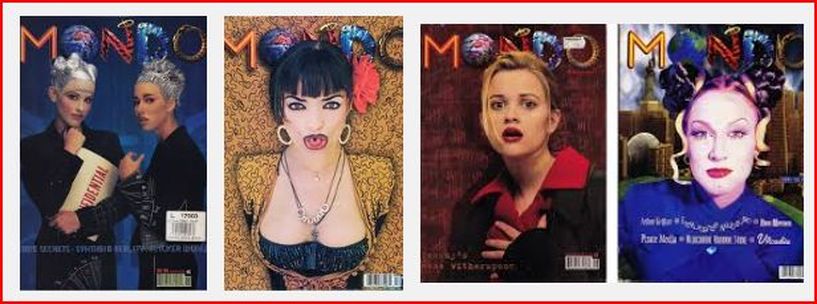

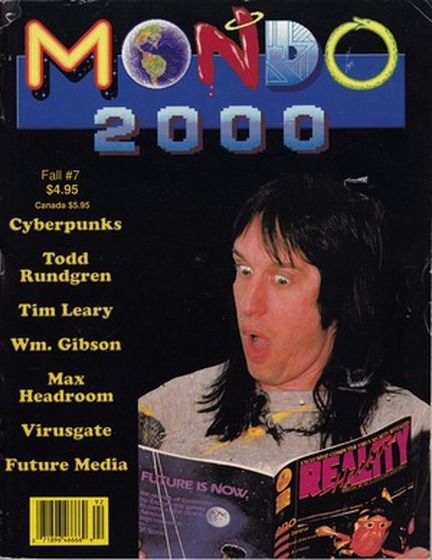

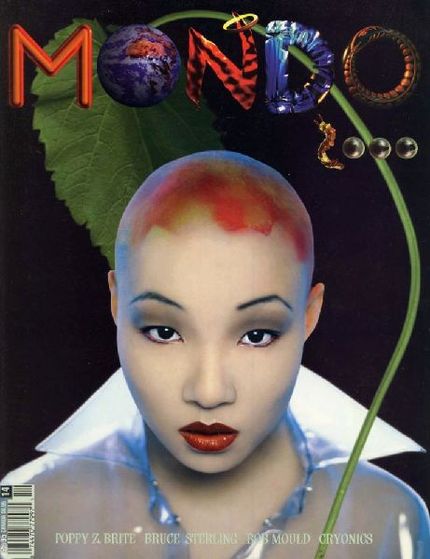

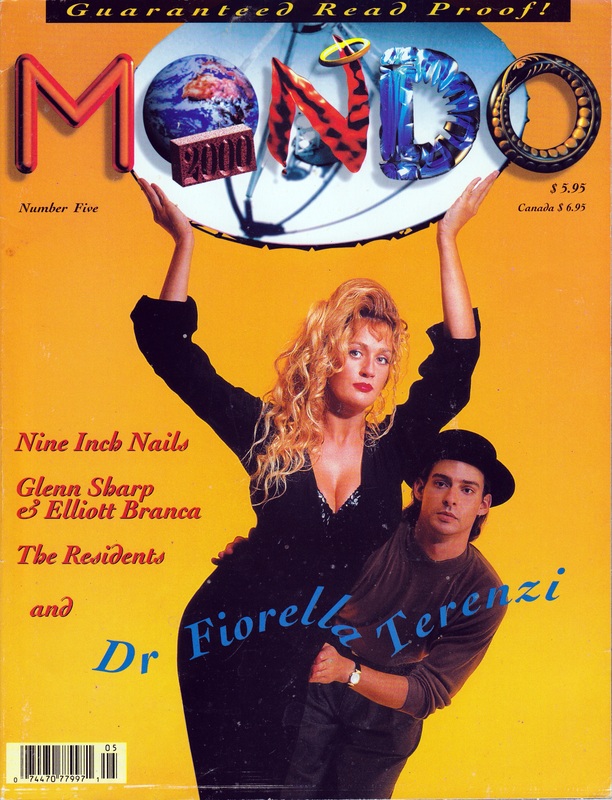

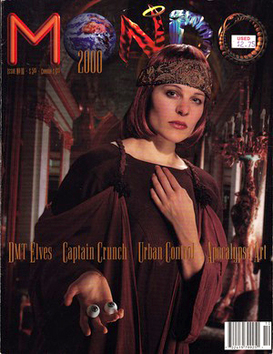

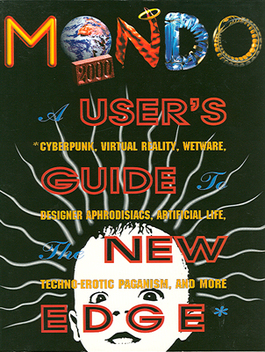

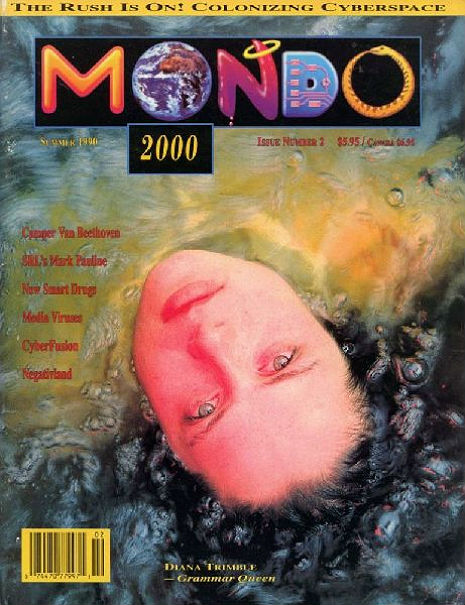

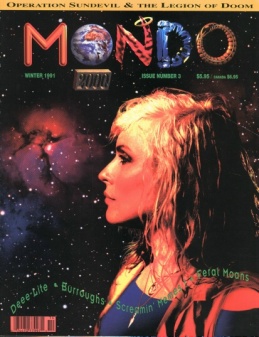

Mondo 2000

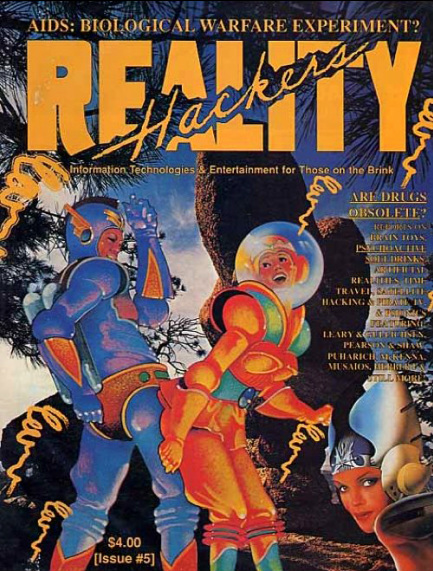

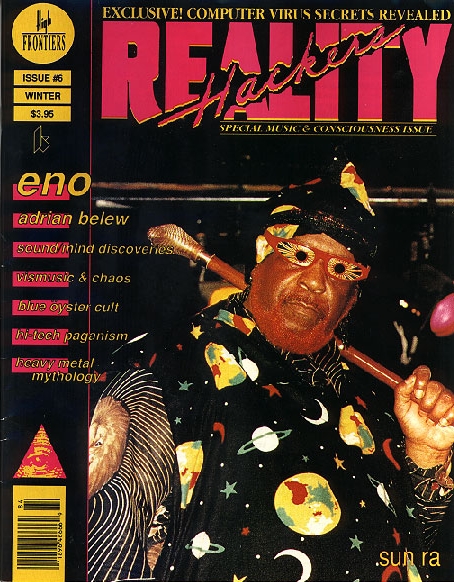

High Frontiers / Reality Hackers

(Berkeley-centered Neo-Psychdelic Scene & Zine)

http://omnireboot.jerrickventures.com/features/the-mondo-moment

High Frontiers / Reality Hackers

(Berkeley-centered Neo-Psychdelic Scene & Zine)

http://omnireboot.jerrickventures.com/features/the-mondo-moment

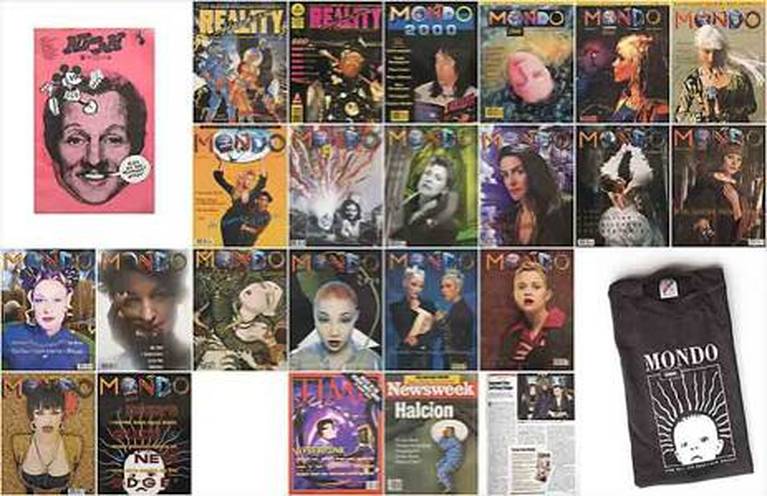

Mondo picked up where Omni magazine left off, with a similar sense of science, tech, and art, but a subcultural approach to irony, irreverence and taboo with the zealousness of a movement. Mondo didn't come out of nowhere. There were journals covering their subject-matter, but not popularized for general consumption. If Omni mated with the hi-gloss photography zine Zoom, Mondo 2000 could be their personality-disordered love child.

From Counterculture to Cyberpunk

http://www2.fiu.edu/~mizrachs/Cyberpunk_as_Counterculture.htm

http://www2.fiu.edu/~mizrachs/Cyberpunk_as_Counterculture.htm

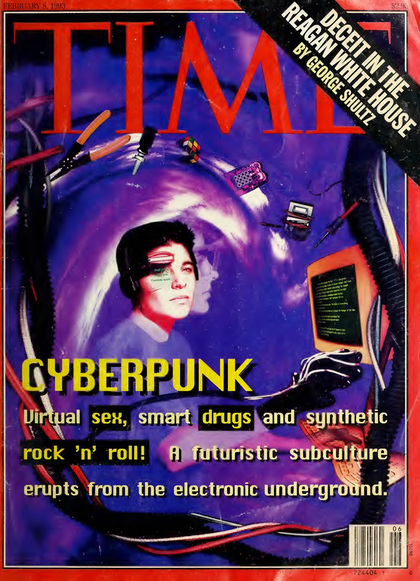

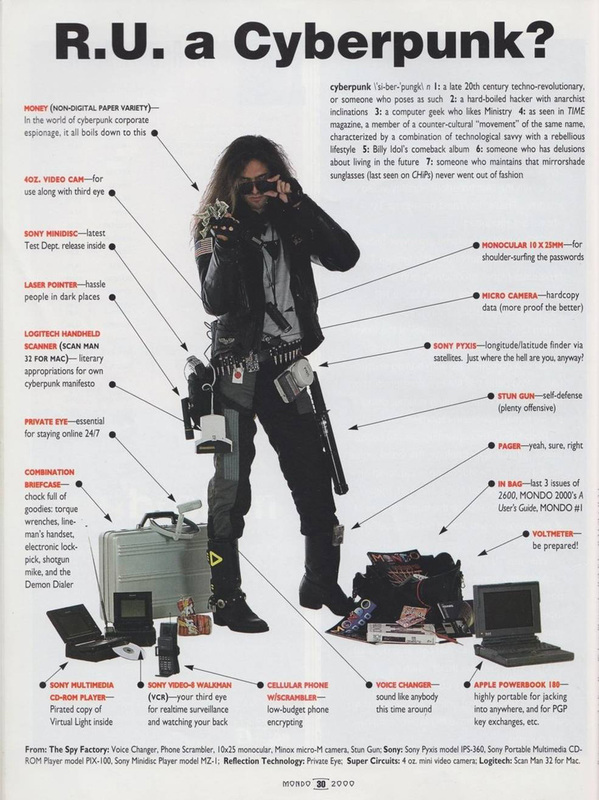

It has long been a truism of American political thought that there is a 30-year cycle of American politics, alternating between conservatism and experimentation. America had just come out of a conservative decade in the 1980s, and everyone was expecting that something like the 1960s would be coming again in the 1990s. To meet this retroexpectation, fashion designers eagerly complied, recycling all kinds of things from earth shoes to Nehru jackets. No one knew what the 90s would bring - people talked about a new fiscal sensibility, a new stay-at-home attitude (cocooning), and maybe a new simplicity. Nothing that really looked like a counterculture; just a cultural retrenchment. And then Time magazine, that great barometer of American life, told us who the counterculture would be: the cyberpunk. A new youth explosion was underway - but this was a Generation Xplosion, which meant taking to the airwaves instead of the streets.

People quickly found out this new counterculture was not quite like the old one. They preferred the rave, with its hyperaccellerated remixed digital music, to simple acoustic folk songs; their drug of choice was Ecstasy, not pot. These were not New Age flower children looking for "peace and love"; instead they were New Edge hiphoppers out for "tech and cred."

Rather than having some kind of 'back to nature' romanticism, these folks preferred the urban disorder of the city, and they saw technology as their weapon of choice, not the enemy. Their heroes were not the Hippies of Peoples' Park - instead they looked to the pioneers of pirate radio as their icons. Not surprisingly, old countercultural types like Timothy Leary, John Perry Barlow, and Robert Anton Wilson quickly joined their ranks, proclaiming cyberpunk was the next wave of struggle against the System and all it stood for.

Their were superficial similarities, of course. The cyberpunks had a curious enthusiasm for neurochemicals, especially ones that they claimed increased energy, intelligence, or memory, although they rejected the idea that drugs might lead to some kind of peace or mystical harmony. They eschewed political activism, civil disobedience, and protest marches. Intead, they preferred a more essential form of the guerrilla strike - one that used the phone lines rather than the picket line. There was no point in asking the Man for anything. Simply pick up your keyboard and take what you want from him, 'cause he won't give it to you. http://www2.fiu.edu/~mizrachs/Cyberpunk_as_Counterculture.htm

Time magazine published an article defining and clarifying questions of the cyberpunk movement. The conventionalization of cyberpunk (CP for short) has succeeded in removing the ideals and philosophies once associated with it. Rudy Rucker states that CP is "simply the fusion of humans and machines (Elmer-Dewitt 59)." However, CP is about much more than that: it is about the struggle between man and its creation, the probing of the human soul, and the rebellion against tradition. http://project.cyberpunk.ru/idb/cyberpunk_confusion.html

People quickly found out this new counterculture was not quite like the old one. They preferred the rave, with its hyperaccellerated remixed digital music, to simple acoustic folk songs; their drug of choice was Ecstasy, not pot. These were not New Age flower children looking for "peace and love"; instead they were New Edge hiphoppers out for "tech and cred."

Rather than having some kind of 'back to nature' romanticism, these folks preferred the urban disorder of the city, and they saw technology as their weapon of choice, not the enemy. Their heroes were not the Hippies of Peoples' Park - instead they looked to the pioneers of pirate radio as their icons. Not surprisingly, old countercultural types like Timothy Leary, John Perry Barlow, and Robert Anton Wilson quickly joined their ranks, proclaiming cyberpunk was the next wave of struggle against the System and all it stood for.

Their were superficial similarities, of course. The cyberpunks had a curious enthusiasm for neurochemicals, especially ones that they claimed increased energy, intelligence, or memory, although they rejected the idea that drugs might lead to some kind of peace or mystical harmony. They eschewed political activism, civil disobedience, and protest marches. Intead, they preferred a more essential form of the guerrilla strike - one that used the phone lines rather than the picket line. There was no point in asking the Man for anything. Simply pick up your keyboard and take what you want from him, 'cause he won't give it to you. http://www2.fiu.edu/~mizrachs/Cyberpunk_as_Counterculture.htm