RIVERBANK LABS

Acoustic Alchemy

Pioneering Esoteric Lab & Think Tank

How Decoding Shakespeare and Levitation Led to NSA

& Helped Win Two World Wars

by Iona Miller, (c)2010, All Rights Reserved

ESOTERICS TO WEIRD SCIENCE

PRO: Riverbank produced book on Baconian Cipher

http://books.google.com/books?id=dPwsAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=riverbank+laboratories&source=bl&ots=0DnT5fZGfh&sig=C1QFk4f3hJ5_-Qw7ADgRQSnxsQE&hl=en&ei=NQu4TLGQGJG-sAP1zYGWDw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CB0Q6AEwAjgK#v=onepage&q&f=false

PRO: Riverbank produced book on Baconian Cipher

http://books.google.com/books?id=dPwsAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=riverbank+laboratories&source=bl&ots=0DnT5fZGfh&sig=C1QFk4f3hJ5_-Qw7ADgRQSnxsQE&hl=en&ei=NQu4TLGQGJG-sAP1zYGWDw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CB0Q6AEwAjgK#v=onepage&q&f=false

Bacon Ciphers in Shakespeare were proposed in The Great Cryptogram by Ignatius Donnelly

http://books.google.com/books?id=Z5INAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22The+Great+Cryptogram%22+Ignatius+Donnelly&source=bl&ots=pR09NdGhvR&sig=BRRZfeXu5XpXS7h_xrB5vkiVz2I&hl=en&ei=jU3nTIjYG4WisAPGib2xCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBMQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

http://books.google.com/books?id=Z5INAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22The+Great+Cryptogram%22+Ignatius+Donnelly&source=bl&ots=pR09NdGhvR&sig=BRRZfeXu5XpXS7h_xrB5vkiVz2I&hl=en&ei=jU3nTIjYG4WisAPGib2xCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBMQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

RIVERBANK THINKTANK,

West of Chicago:

From a Baconian Levitation Machine to Acoustic Alchemy

How a Seemingly Failed Levitation Machine Led to the Founding of NSA & the Secrets of Ciphers

First Thinktank * First Privately Owned Research Laboratory * First US Decryptions * Genetics * Acoustics

Original US Esoterics Lab & Thinktank

"Some rich men go in for art collections, gay times on the Riviera, or extravagant living. But they all get satiated. That’s why I stick to scientific experiments, spending money to discover valuable things that universities can’t afford. You never get sick of too much knowledge." --Col. George Fabyan

"Less Noise; More Hearing": Geneva, Illinois. Riverbank Engineering Bldg.

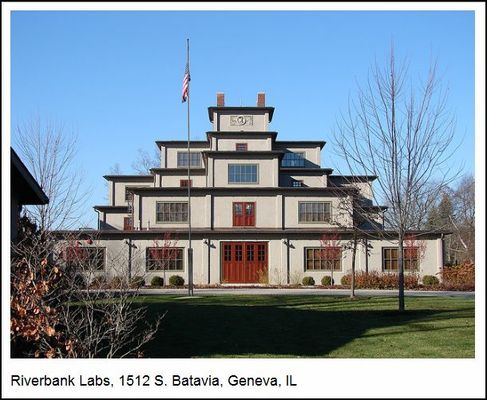

Somewhere between a step pyramid and Tibetan architecture, Riverbank Labs reflects the eccentricities of its builder. The Villa residence, 40 miles west of Chicago, is now a museum that houses collections of photos and memorabilia of cotton-fortune heir Col. George Fabyan. The Villa was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1907. In 1914, landscape architect Taro Otsuka designed Fabyan’s Japanese Garden. An imported Dutch windmill stands in another portion of the 600-acre estate. The garden was restored in 1971 and again in 1994, and is open to the public.

Many different research activities occurred at Riverbank, including decoding and deciphering enemy messages during World War I, deciphering alleged secret messages in the works of William Shakespeare, research in the field of architectural acoustics, groundbreaking research in the field of cryptology, fieldwork in the use of hand grenades and military trenches, research and development of tuning forks, and studies of human fitness and anatomy. Teams of researchers lived and worked at Riverbank, devoting years of their lives to frontier science. Many scientists from around the nation and world have visited Riverbank and stayed at The Lodge. The United State’s military successes in World War I and World War II were supported by Riverbank, which is a direct lineal predecessor of the National Security Agency and Central Intelligence Agency.

As Friedman and his staff in the Riverbank Department of Codes and Ciphers worked on solving messages coming in from various federal agencies and foreign governments, they became the first unofficial cryptologic organization in the United States. It was still many months before Military Intelligence was formed as the nation’s first official cipher bureau. Friedman invented the words "cryptanalysis" and "cryptology", the first being code-breaking, and the latter being the overall term used to describe the science. In 1929, he became widely known as one of the world’s leading authorities on cryptology when the Encyclopedia Britannica published his article on "Codes and Ciphers." The Black Chamber was dissolved in 1929 and the Signal Intelligence Service was created with William Friedman as its first director. His first task was to set up an adequate program to provide training for officers in cryptology. The result was the Signal Intelligence School. He also wrote three textbooks on military cryptography for these courses. These comprise the finest, most lucid exposition of the solution of basic ciphers that has ever been published. The Black Chamber, otherwise known as MI-8 or Cipher Bureau, was the United States' first peacetime cryptanalytic organization, and a forerunner of the National Security Agency. The only prior codes and cypher organizations maintained by the US government had been some intermittent, and always abandoned, attempts by Armed Forces branches prior to World War I.

The American Black Chamber By Herbert Osborn Yardley

http://books.google.com/books?id=Y2GI32l-hXIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22The+Black+chamber%22&source=bll&ots=xg4UEBzEhn&sig=D4sT-ij1zkXbSmytjinLpUietnY&hl=en&ei=Kbe4TKPWPJDksQPH74D7Dw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=11&ved=0CEQQ6AEwCg#v=onepage&q&f=false

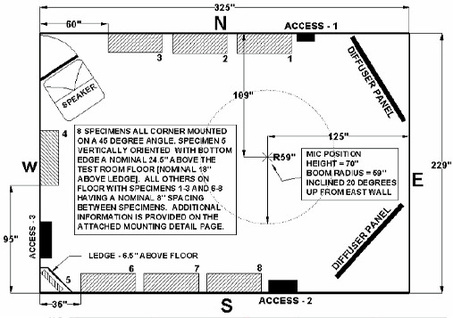

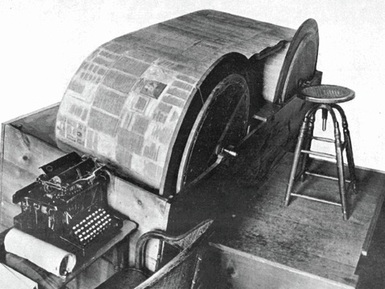

BACON & SCRAMBLED CIPHERS: Eventually, Fabyan’s estate grew to cover 600 acres and was the home to award-winning flowers, livestock and other animals. Fabyan imported scientists from the fields of plant genetics and acoustics as well as cryptography to his estate. The cryptographers were mainly there to prove that Bacon wrote Shakespeare's plays, but still ended up being the foundation for the NSA. Under the theoretical spell of Elizebeth Wells Gallup, Fabyan read in one of Bacon's works a description of a levitation device that allegedly worked on acoustic principles. He built one, but couldn't get it to fly, so he sent to Harvard University for some acoustic experts to help him. Revealed by the code, previously known only to the Rosicrucians, is an acoustical levitating machine. A huge drum with piano strings stretched along its surface is rotated within an outer casing with corresponding strings. As the strings vibrate, the outer shell is made to levitate.

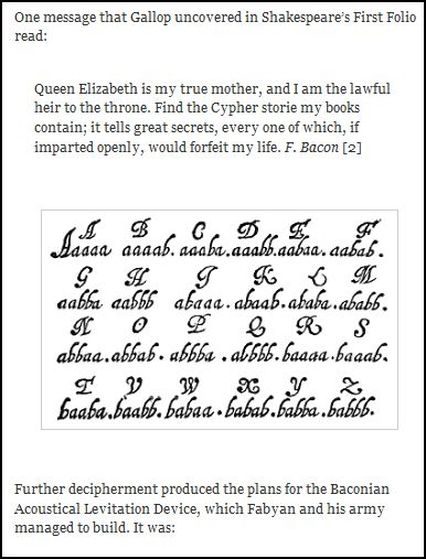

It had been known for some time that Francis Bacon belonged to a secret society called the Rosicrucian Society. They believed in conducting scientific experiments that in those times was often considered witchcraft. Due to Bacon’s position with the Queen of England, he ran the Queen’s printing press, and had devised what was called a biliteral cipher utilizing wide and thin letters to represent the alphabet. Colonel Fabyan also believed in the Baconian theory. Mrs. Gallup believed Bacon was the real Shakespeare for two reasons: 1) Bacon had invented the biliteral cipher and used it in printed publications, and 2) the original printed folios of Shakespeare’s plays used a variety of different typefaces.

So goes the theory; trouble is, it doesn't work. Or, at least acoustic alchemy had not yet come into its own. Fabyan invited the famous professor Wallace Sabine to his estate to study the problem. The professor made a few calculations, and convinced Fabyan there would never be enough sound energy to lift anything. Might the old gentleman be interested in underwriting some genuine scientific research, such as a reverberation chamber?

So began decades of discovery: Sabine's formula for sound absorption is still used in many standard acoustical tests, and the unit of absorption now bears his name, "sabin." The wonders recorded included sound absorbers that seemed to absorb more sound than fell upon them; an acoustical consultant, never hired for a certain concert hall project, who was criticized for its poor acoustics (while another acoustical consultant was praised for the excellent acoustics of the very same hall); the standard color of sound used in an acoustical laboratory; the required height, weight and shoes for a lady floor-walker; and much, much more, equally exotic.

The Colonel died May 17, 1936; his wife died two years later, and the executors of her will sold Riverbank to the Kane County Forest Preserve for $70,500. Various guests to the estate supposedly included Albert Einstein, P.T. Barnum and Wallace Clement Sabine (American physicist and pioneer founder of the field of architectural acoustics). The work in cryptology done there by William Friedman, work in acoustical research done by Wallace Clement and Paul (a distant cousin) Sabine, and Fabyan's strange desire to prove that the works of Shakespeare were in fact not written by Shakespeare but contained Baconian ciphers. Elizabeth Wells Gallup studied Shakepeare’s First Folio to see if the differences in variations of type represented Bacon’s use of the biliteral cipher. One of the messages she deciphered was: "Queen Elizabeth is my true mother, and I am the lawful heir to the throne. Find the Cypher storie my books contain; it tells great secrets, every one of which, if imparted openly, would forfeit my life. F. Bacon" They also worked unsuccessfully on the inscrutable Voynich Manuscript.

One of the scientific experiments documented by Sir Francis Bacon was a levitating machine.

The machine was a wooden tube with metal strings attached to it, around which fit another wooden tube with metal strings attached to the inside of it. The center tube was supposed to spin and by sympathetic vibration cause the strings on the outer tube to vibrate. The resonance from the striking would create a force field, which would levitate the outer tube off of the ground. Colonel Fabyan hired Bert Eisenhour, an engineer from Chicago, to construct this machine at Riverbank. Though the machine was constructed, it did not work. Eisenhour was convinced that the strings were not tuned properly, and suggested they consult someone knowledgeable in acoustics.

Decipherment from Shakespeare's first folio produced the plans for the Baconian Acoustical Levitation Device, which Fabyan and his army managed to build. [See photo] It was: A wooden tube with metal strings attached to it, around which fit another wooden tube with metal strings attached to the inside of it. The center tube was supposed to spin and by sympathetic vibration cause the strings on the outer tube to vibrate. The resonance from the striking would create a force field, which would levitate the outer tube off of the ground.

First Thinktank * First Privately Owned Research Laboratory * First US Decryptions * Genetics * Acoustics

Original US Esoterics Lab & Thinktank

"Some rich men go in for art collections, gay times on the Riviera, or extravagant living. But they all get satiated. That’s why I stick to scientific experiments, spending money to discover valuable things that universities can’t afford. You never get sick of too much knowledge." --Col. George Fabyan

"Less Noise; More Hearing": Geneva, Illinois. Riverbank Engineering Bldg.

Somewhere between a step pyramid and Tibetan architecture, Riverbank Labs reflects the eccentricities of its builder. The Villa residence, 40 miles west of Chicago, is now a museum that houses collections of photos and memorabilia of cotton-fortune heir Col. George Fabyan. The Villa was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1907. In 1914, landscape architect Taro Otsuka designed Fabyan’s Japanese Garden. An imported Dutch windmill stands in another portion of the 600-acre estate. The garden was restored in 1971 and again in 1994, and is open to the public.

Many different research activities occurred at Riverbank, including decoding and deciphering enemy messages during World War I, deciphering alleged secret messages in the works of William Shakespeare, research in the field of architectural acoustics, groundbreaking research in the field of cryptology, fieldwork in the use of hand grenades and military trenches, research and development of tuning forks, and studies of human fitness and anatomy. Teams of researchers lived and worked at Riverbank, devoting years of their lives to frontier science. Many scientists from around the nation and world have visited Riverbank and stayed at The Lodge. The United State’s military successes in World War I and World War II were supported by Riverbank, which is a direct lineal predecessor of the National Security Agency and Central Intelligence Agency.

As Friedman and his staff in the Riverbank Department of Codes and Ciphers worked on solving messages coming in from various federal agencies and foreign governments, they became the first unofficial cryptologic organization in the United States. It was still many months before Military Intelligence was formed as the nation’s first official cipher bureau. Friedman invented the words "cryptanalysis" and "cryptology", the first being code-breaking, and the latter being the overall term used to describe the science. In 1929, he became widely known as one of the world’s leading authorities on cryptology when the Encyclopedia Britannica published his article on "Codes and Ciphers." The Black Chamber was dissolved in 1929 and the Signal Intelligence Service was created with William Friedman as its first director. His first task was to set up an adequate program to provide training for officers in cryptology. The result was the Signal Intelligence School. He also wrote three textbooks on military cryptography for these courses. These comprise the finest, most lucid exposition of the solution of basic ciphers that has ever been published. The Black Chamber, otherwise known as MI-8 or Cipher Bureau, was the United States' first peacetime cryptanalytic organization, and a forerunner of the National Security Agency. The only prior codes and cypher organizations maintained by the US government had been some intermittent, and always abandoned, attempts by Armed Forces branches prior to World War I.

The American Black Chamber By Herbert Osborn Yardley

http://books.google.com/books?id=Y2GI32l-hXIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22The+Black+chamber%22&source=bll&ots=xg4UEBzEhn&sig=D4sT-ij1zkXbSmytjinLpUietnY&hl=en&ei=Kbe4TKPWPJDksQPH74D7Dw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=11&ved=0CEQQ6AEwCg#v=onepage&q&f=false

BACON & SCRAMBLED CIPHERS: Eventually, Fabyan’s estate grew to cover 600 acres and was the home to award-winning flowers, livestock and other animals. Fabyan imported scientists from the fields of plant genetics and acoustics as well as cryptography to his estate. The cryptographers were mainly there to prove that Bacon wrote Shakespeare's plays, but still ended up being the foundation for the NSA. Under the theoretical spell of Elizebeth Wells Gallup, Fabyan read in one of Bacon's works a description of a levitation device that allegedly worked on acoustic principles. He built one, but couldn't get it to fly, so he sent to Harvard University for some acoustic experts to help him. Revealed by the code, previously known only to the Rosicrucians, is an acoustical levitating machine. A huge drum with piano strings stretched along its surface is rotated within an outer casing with corresponding strings. As the strings vibrate, the outer shell is made to levitate.

It had been known for some time that Francis Bacon belonged to a secret society called the Rosicrucian Society. They believed in conducting scientific experiments that in those times was often considered witchcraft. Due to Bacon’s position with the Queen of England, he ran the Queen’s printing press, and had devised what was called a biliteral cipher utilizing wide and thin letters to represent the alphabet. Colonel Fabyan also believed in the Baconian theory. Mrs. Gallup believed Bacon was the real Shakespeare for two reasons: 1) Bacon had invented the biliteral cipher and used it in printed publications, and 2) the original printed folios of Shakespeare’s plays used a variety of different typefaces.

So goes the theory; trouble is, it doesn't work. Or, at least acoustic alchemy had not yet come into its own. Fabyan invited the famous professor Wallace Sabine to his estate to study the problem. The professor made a few calculations, and convinced Fabyan there would never be enough sound energy to lift anything. Might the old gentleman be interested in underwriting some genuine scientific research, such as a reverberation chamber?

So began decades of discovery: Sabine's formula for sound absorption is still used in many standard acoustical tests, and the unit of absorption now bears his name, "sabin." The wonders recorded included sound absorbers that seemed to absorb more sound than fell upon them; an acoustical consultant, never hired for a certain concert hall project, who was criticized for its poor acoustics (while another acoustical consultant was praised for the excellent acoustics of the very same hall); the standard color of sound used in an acoustical laboratory; the required height, weight and shoes for a lady floor-walker; and much, much more, equally exotic.

The Colonel died May 17, 1936; his wife died two years later, and the executors of her will sold Riverbank to the Kane County Forest Preserve for $70,500. Various guests to the estate supposedly included Albert Einstein, P.T. Barnum and Wallace Clement Sabine (American physicist and pioneer founder of the field of architectural acoustics). The work in cryptology done there by William Friedman, work in acoustical research done by Wallace Clement and Paul (a distant cousin) Sabine, and Fabyan's strange desire to prove that the works of Shakespeare were in fact not written by Shakespeare but contained Baconian ciphers. Elizabeth Wells Gallup studied Shakepeare’s First Folio to see if the differences in variations of type represented Bacon’s use of the biliteral cipher. One of the messages she deciphered was: "Queen Elizabeth is my true mother, and I am the lawful heir to the throne. Find the Cypher storie my books contain; it tells great secrets, every one of which, if imparted openly, would forfeit my life. F. Bacon" They also worked unsuccessfully on the inscrutable Voynich Manuscript.

One of the scientific experiments documented by Sir Francis Bacon was a levitating machine.

The machine was a wooden tube with metal strings attached to it, around which fit another wooden tube with metal strings attached to the inside of it. The center tube was supposed to spin and by sympathetic vibration cause the strings on the outer tube to vibrate. The resonance from the striking would create a force field, which would levitate the outer tube off of the ground. Colonel Fabyan hired Bert Eisenhour, an engineer from Chicago, to construct this machine at Riverbank. Though the machine was constructed, it did not work. Eisenhour was convinced that the strings were not tuned properly, and suggested they consult someone knowledgeable in acoustics.

Decipherment from Shakespeare's first folio produced the plans for the Baconian Acoustical Levitation Device, which Fabyan and his army managed to build. [See photo] It was: A wooden tube with metal strings attached to it, around which fit another wooden tube with metal strings attached to the inside of it. The center tube was supposed to spin and by sympathetic vibration cause the strings on the outer tube to vibrate. The resonance from the striking would create a force field, which would levitate the outer tube off of the ground.

Levitation with Acoustics Actually Does Work

Investigative journalist, Charles W. Stone of MRU claims, "I did find evidence and a wood model of a device at the Geneva History Center of a "Baconian levitation device." It reportedly was workable, in principle. It is only a few steps to time travel. The Time travel which was developed by DARPA and the CIA after WW II was based on specialized music at The Vatican. (Also a form of acoustics)."

Chronovision allegedly came from the Vatican-based music experiments in the 50s. Chronovisor, a type of time machine which would bring pictures and sounds from the past into the present. Looking a bit like a television, the machine worked by detecting all the sights and sounds that humanity had made that still floated through space. The Chronovisor was portrayed as a large cabinet with a normal cathode ray tube for viewing the received events and a series of buttons, levers, and other controls for selecting the time and the location to be viewed. It could also focus and track specific people. According to its inventor, Father Pellegrino Ernetti, it worked by receiving, decoding and reproducing the electromagnetic radiation left behind from past events, though it could also pick up sound waves. Ernetti began by filtering harmonics from Gregorian chants. Instead they heard paranormal voices. The Pope wanted them to confirm faith in the Beyond.

Ernetti formulated theories to answer the questions: what happened to all the sights and sounds humans make? Did they disappear completely or do they continue to exist in some way? Through Papal connections and backing, he was introduced to a team of 12 of the world’s greatest scientific minds in order to further this research. A team which included Enrico Fermi, winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1938 and designer of the world’s first nuclear reactor, as well as NASA rocket scientist Werner Von Braun, former SS Colonel, head of the Nazi rocket program and later the man who would lead the American Apollo space program. The research was conducted in complete secrecy, with no leaks or mentions made until the early 1960’s. The machine was supposedly destroyed.

It is possible that time travel was also investigated earlier at Riverbank Labs as there is a similarity to acoustics and music.

It does appear that levitation was also developed there. There is a relationship between standing waves and musical instruments. Resonance is a fundamental principle from micro to macrocosm as are harmonics. Musical tones are produced by musical instruments, or by the voice, which, from a physics perspective, is a very complex wind instrument. So the physics of music is the physics of the kinds of sounds these instruments can make. What kinds of sounds are these? They are tones caused by standing waves produced in or on the instrument. So the properties of these standing waves, which are always produced in very specific groups, or series, have far-reaching effects on music theory.

Most sound waves, including the musical sounds that actually reach our ears, are not standing waves. Normally, when something makes a wave, the wave travels outward, gradually spreading out and losing strength, like the waves moving away from a pebble dropped into a pond. But when the wave encounters something, it can bounce (reflection) or be bent (refraction). In fact, you can "trap" waves by making them bounce back and forth between two or more surfaces. Musical instruments take advantage of this; they produce pitches by trapping sound waves. Why are trapped waves useful for music? Any bunch of sound waves will produce some sort of noise. But to be a tone - a sound with a particular pitch - a group of sound waves has to be very regular, all exactly the same distance apart. That's why we can talk about the frequency and wavelength of tones.

You can produce a tone in a sound wave trap and keep sending more sound waves into it. Picture a lot of pebbles dropped into a very small pool. As the waves start reflecting off the edges of the pond, they interfere with the new waves, making a jumble of waves that partly cancel each other out and mostly just roils the pond - noise. But if you arrange the waves so that reflecting waves, instead of canceling out the new waves reinforce them, the high parts of the reflected waves meet the high parts of the oncoming waves and make them even higher. The low parts of the reflected waves would meet the low parts of the oncoming waves and make them even lower. Instead of a roiled mess of waves canceling each other out, we find a pond of perfectly ordered waves, with high points and low points appearing regularly at the same spots again and again. A single wave can reflect back and forth and standing waves.

Riverbank Lab was a giant resonant chamber, essentially an acoustic instrument.

Orderliness is actually hard to get from water waves, but relatively easy to get in sound waves, so that several completely different types of sound wave "containers" have been developed into musical instruments. The two most common are strings and hollow tubes. In order to get the necessary constant reinforcement, the container has to be the perfect size (length) for a certain wavelength, so that waves bouncing back or being produced at each end reinforce each other, instead of interfering with each other and canceling each other out. And it really helps to keep the container very narrow, so that you don't have to worry about waves bouncing off the sides and complicating things. So you have a bunch of regularly-spaced waves that are trapped, bouncing back and forth in a container that fits their wavelength perfectly. If you could watch these waves, it would not even look as if they are traveling back and forth. Instead, waves would seem to be appearing and disappearing regularly at exactly the same spots, so these trapped waves are called standing waves.

According to Charles Stone, Enrico Fermi was involved in acoustics and time travel. Riverbank was for many years the leading acoustics testing facility in the world. So that fits in with the time travel story. Riverbank is operated or maintained now by a medium sized high tech company in Tyson's Corner. The CEO was formerly the President of Illinois Institute of Technology which is closely linked to Riverbank. I know most of the senior Execs of the company of which a number are retired Navy and Army officers. The CEO even calls his own home The Villa, like the residence at Riverbank.

Iona Miller reports from 2008-2010 contact with Black Swan "Julian West": "This is of utmost importance to one of my own obsessive investigations. My paternal grandfather worked at the legendary Riverbank Labs for the infamous Col. George Fabyan. One of the many controversial/occult studies undertaken at Riverbank was the attempt to prove that Shakespeare was Bacon. (Elizebeth Friedman, for example, was one of Fabyan's most important colleagues. It is through her work that a connection can be established between Fabyan and Atlantis-scholar Ignatius Donnelly.)

Also conducted at Riverbank: Experiments in teleportation and acoustic time-travel via the use of acoustics.

Quantum teleportation of electrons in quantum wires with surface acoustic waves. lionization and trigger the formation of ion-acoustic oscillations. The external triggers may initiate spontaneous teleportation. In 1931, Charles Fort, an American writer, tried to describe the random disappearances and appearances of different anomalies. He felt that these sudden disappearances and appearances were connected and therefore felt that they were "teleporting." While he came up with this theory to try and explain why certain paranormal phenomena acted, many suggest that Fort probably didn't subscribe to the theory and was using it as a way of suggesting mainstream science didn't provide enough information on why these phenomena happened.

Dematerialising This is the transmission of data from one area and then the reconstruction of that object at its final destination. This is a theory that is presented in Star Trek when the individuals are "beamed down" to the planet. While the uncertainty principle suggests that humans are unable to be dematerialized because rebuilding their body as perfectly as they had previously been is nearly impossible. However, in 1998, scientists at Caltech were able to make a true teleportation occur. This resulted in energy being transmitted from one point to another with a distance of about one meter. While the scientists admit that it was only one meter, they argue that they feel they could make the energy transmit to distances much larger.

Dimensional Teleportation This theory of teleportation suggests that an object existing in one universe leaves that universe, enters another one and then returns to the original, but in a different place. However, this theory is not considered often because it goes against the argument that time travel is not possible. Wormhole According to some, a wormhole is a shortcut through time and space. It is suggested that an individual could go into a wormhole and this would be the "effective" method of getting from point A to point B without needing any form of time travel machines. However, little is known about whether these wormholes actually exist or not. Is Teleportation Possible? Teleportation has always been a sign of intrigue in the science fiction world; however, there is still little research available to suggest whether teleportation is actually possible. There have been successful experiments, though, that suggest that teleportation is possible. However, since this is only energy, it is argued that it would take a considerable amount of time to create a method of teleporting an individual. Even then, there are so many theories that suggest that it is impossible because regnerating a human would be nearly impossible.

West continues, "My grandfather had a very old set of Shakespeare's complete works (heavily annotated in more than one handwriting), which is now unfortunately lost, due to the ignorance and carelessness of his widow. (He never discussed the true nature of his work with his family; I myself have spent free time over several years just beginning to gather some real facts together (--discovering your work, linking Bacon to St. Germain, may be a big breakthrough in this research into the true nature and import of the experimental research conducted at Riverbank)). I also have in my own possession a few artifacts from Fabyan's estate, which came down from my grandfather."

Ms. Miller began investigating Riverbank Labs in 2006 with another high IQ MRU alumni, a spy-entist with intelligence connections, (a former military intel internal security officer) responding to questions about the NSA cryptographer in Dan Brown's proposal on "Solomon's Key" which appeared later as the book "Lost Symbol." The father of his childhood friend "disposed of the incriminating walk-in vaults in old NSA HQ at Riverbank Labs....the first overt attempt to voluntarily recruit me was Jan 4, 1967 at that same Riverbank Labs."

The MRU spyentist continues, "I wasn't excited about the spiel Carl [Schleicher] apparently agreed to. I had been warned two years previously by Dale Williams, son of Riverbank director, and also in 6th grade by Mrs. Jones, former OSS cipherhead. I took those warnings lightly until personnel got used up due to Viet Nam and TEXACO-linked side of NSA started using heavier tactics like extortion, threats and financial incentives. The author, William Shirer and son in law of Joe McCarthy (William Tierney) were both close friends of Friedman but never disclosed that, as far as I know. Shirer almost killed himself because he thought nobody would read Rise and Fall of Third Reich; he was also an associate of NSA/Norris at Tribune. I am pleased to contest any difference between what I say and NSA official version, with perfect confidence. They probably they won't even try. You might see that I fill in the large blank spots in official history." "Don't ever think that NSA began in 1952. I've seen their charter and it isn't the public one. Until 1970, NSA considered themselves the real OSS and they were run until 1990 by about 10 military men most of whom were among the few who managed to fight back effectively on Dec 7, 1941. They considered NSA Directors and US Presidents to be hired help and figureheads. BTW, Elizebeth Smith Friedman was a cousin of Dan Quayle's wife."

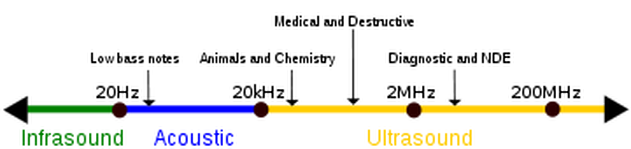

Long Range Acoustic Devices are now used for crowd control along with other Directed Energy Weapons (DEW). Ultrasound is cyclic sound pressure with a frequency greater than the upper limit of human hearing. Although this limit varies from person to person, it is approximately 20 kilohertz (20,000 hertz) in healthy, young adults and thus, 20 kHz serves as a useful lower limit in describing ultrasound. The production of ultrasound is used in many different fields, typically to penetrate a medium and measure the reflection signature or supply focused energy. The reflection signature can reveal details about the inner structure of the medium, a property also used by animals such as bats for hunting. The most well known application of ultrasound is its use in sonography to produce pictures of foetuses in the human womb. There are a vast number of other applications as well.

Chronovision allegedly came from the Vatican-based music experiments in the 50s. Chronovisor, a type of time machine which would bring pictures and sounds from the past into the present. Looking a bit like a television, the machine worked by detecting all the sights and sounds that humanity had made that still floated through space. The Chronovisor was portrayed as a large cabinet with a normal cathode ray tube for viewing the received events and a series of buttons, levers, and other controls for selecting the time and the location to be viewed. It could also focus and track specific people. According to its inventor, Father Pellegrino Ernetti, it worked by receiving, decoding and reproducing the electromagnetic radiation left behind from past events, though it could also pick up sound waves. Ernetti began by filtering harmonics from Gregorian chants. Instead they heard paranormal voices. The Pope wanted them to confirm faith in the Beyond.

Ernetti formulated theories to answer the questions: what happened to all the sights and sounds humans make? Did they disappear completely or do they continue to exist in some way? Through Papal connections and backing, he was introduced to a team of 12 of the world’s greatest scientific minds in order to further this research. A team which included Enrico Fermi, winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1938 and designer of the world’s first nuclear reactor, as well as NASA rocket scientist Werner Von Braun, former SS Colonel, head of the Nazi rocket program and later the man who would lead the American Apollo space program. The research was conducted in complete secrecy, with no leaks or mentions made until the early 1960’s. The machine was supposedly destroyed.

It is possible that time travel was also investigated earlier at Riverbank Labs as there is a similarity to acoustics and music.

It does appear that levitation was also developed there. There is a relationship between standing waves and musical instruments. Resonance is a fundamental principle from micro to macrocosm as are harmonics. Musical tones are produced by musical instruments, or by the voice, which, from a physics perspective, is a very complex wind instrument. So the physics of music is the physics of the kinds of sounds these instruments can make. What kinds of sounds are these? They are tones caused by standing waves produced in or on the instrument. So the properties of these standing waves, which are always produced in very specific groups, or series, have far-reaching effects on music theory.

Most sound waves, including the musical sounds that actually reach our ears, are not standing waves. Normally, when something makes a wave, the wave travels outward, gradually spreading out and losing strength, like the waves moving away from a pebble dropped into a pond. But when the wave encounters something, it can bounce (reflection) or be bent (refraction). In fact, you can "trap" waves by making them bounce back and forth between two or more surfaces. Musical instruments take advantage of this; they produce pitches by trapping sound waves. Why are trapped waves useful for music? Any bunch of sound waves will produce some sort of noise. But to be a tone - a sound with a particular pitch - a group of sound waves has to be very regular, all exactly the same distance apart. That's why we can talk about the frequency and wavelength of tones.

You can produce a tone in a sound wave trap and keep sending more sound waves into it. Picture a lot of pebbles dropped into a very small pool. As the waves start reflecting off the edges of the pond, they interfere with the new waves, making a jumble of waves that partly cancel each other out and mostly just roils the pond - noise. But if you arrange the waves so that reflecting waves, instead of canceling out the new waves reinforce them, the high parts of the reflected waves meet the high parts of the oncoming waves and make them even higher. The low parts of the reflected waves would meet the low parts of the oncoming waves and make them even lower. Instead of a roiled mess of waves canceling each other out, we find a pond of perfectly ordered waves, with high points and low points appearing regularly at the same spots again and again. A single wave can reflect back and forth and standing waves.

Riverbank Lab was a giant resonant chamber, essentially an acoustic instrument.

Orderliness is actually hard to get from water waves, but relatively easy to get in sound waves, so that several completely different types of sound wave "containers" have been developed into musical instruments. The two most common are strings and hollow tubes. In order to get the necessary constant reinforcement, the container has to be the perfect size (length) for a certain wavelength, so that waves bouncing back or being produced at each end reinforce each other, instead of interfering with each other and canceling each other out. And it really helps to keep the container very narrow, so that you don't have to worry about waves bouncing off the sides and complicating things. So you have a bunch of regularly-spaced waves that are trapped, bouncing back and forth in a container that fits their wavelength perfectly. If you could watch these waves, it would not even look as if they are traveling back and forth. Instead, waves would seem to be appearing and disappearing regularly at exactly the same spots, so these trapped waves are called standing waves.

According to Charles Stone, Enrico Fermi was involved in acoustics and time travel. Riverbank was for many years the leading acoustics testing facility in the world. So that fits in with the time travel story. Riverbank is operated or maintained now by a medium sized high tech company in Tyson's Corner. The CEO was formerly the President of Illinois Institute of Technology which is closely linked to Riverbank. I know most of the senior Execs of the company of which a number are retired Navy and Army officers. The CEO even calls his own home The Villa, like the residence at Riverbank.

Iona Miller reports from 2008-2010 contact with Black Swan "Julian West": "This is of utmost importance to one of my own obsessive investigations. My paternal grandfather worked at the legendary Riverbank Labs for the infamous Col. George Fabyan. One of the many controversial/occult studies undertaken at Riverbank was the attempt to prove that Shakespeare was Bacon. (Elizebeth Friedman, for example, was one of Fabyan's most important colleagues. It is through her work that a connection can be established between Fabyan and Atlantis-scholar Ignatius Donnelly.)

Also conducted at Riverbank: Experiments in teleportation and acoustic time-travel via the use of acoustics.

Quantum teleportation of electrons in quantum wires with surface acoustic waves. lionization and trigger the formation of ion-acoustic oscillations. The external triggers may initiate spontaneous teleportation. In 1931, Charles Fort, an American writer, tried to describe the random disappearances and appearances of different anomalies. He felt that these sudden disappearances and appearances were connected and therefore felt that they were "teleporting." While he came up with this theory to try and explain why certain paranormal phenomena acted, many suggest that Fort probably didn't subscribe to the theory and was using it as a way of suggesting mainstream science didn't provide enough information on why these phenomena happened.

Dematerialising This is the transmission of data from one area and then the reconstruction of that object at its final destination. This is a theory that is presented in Star Trek when the individuals are "beamed down" to the planet. While the uncertainty principle suggests that humans are unable to be dematerialized because rebuilding their body as perfectly as they had previously been is nearly impossible. However, in 1998, scientists at Caltech were able to make a true teleportation occur. This resulted in energy being transmitted from one point to another with a distance of about one meter. While the scientists admit that it was only one meter, they argue that they feel they could make the energy transmit to distances much larger.

Dimensional Teleportation This theory of teleportation suggests that an object existing in one universe leaves that universe, enters another one and then returns to the original, but in a different place. However, this theory is not considered often because it goes against the argument that time travel is not possible. Wormhole According to some, a wormhole is a shortcut through time and space. It is suggested that an individual could go into a wormhole and this would be the "effective" method of getting from point A to point B without needing any form of time travel machines. However, little is known about whether these wormholes actually exist or not. Is Teleportation Possible? Teleportation has always been a sign of intrigue in the science fiction world; however, there is still little research available to suggest whether teleportation is actually possible. There have been successful experiments, though, that suggest that teleportation is possible. However, since this is only energy, it is argued that it would take a considerable amount of time to create a method of teleporting an individual. Even then, there are so many theories that suggest that it is impossible because regnerating a human would be nearly impossible.

West continues, "My grandfather had a very old set of Shakespeare's complete works (heavily annotated in more than one handwriting), which is now unfortunately lost, due to the ignorance and carelessness of his widow. (He never discussed the true nature of his work with his family; I myself have spent free time over several years just beginning to gather some real facts together (--discovering your work, linking Bacon to St. Germain, may be a big breakthrough in this research into the true nature and import of the experimental research conducted at Riverbank)). I also have in my own possession a few artifacts from Fabyan's estate, which came down from my grandfather."

Ms. Miller began investigating Riverbank Labs in 2006 with another high IQ MRU alumni, a spy-entist with intelligence connections, (a former military intel internal security officer) responding to questions about the NSA cryptographer in Dan Brown's proposal on "Solomon's Key" which appeared later as the book "Lost Symbol." The father of his childhood friend "disposed of the incriminating walk-in vaults in old NSA HQ at Riverbank Labs....the first overt attempt to voluntarily recruit me was Jan 4, 1967 at that same Riverbank Labs."

The MRU spyentist continues, "I wasn't excited about the spiel Carl [Schleicher] apparently agreed to. I had been warned two years previously by Dale Williams, son of Riverbank director, and also in 6th grade by Mrs. Jones, former OSS cipherhead. I took those warnings lightly until personnel got used up due to Viet Nam and TEXACO-linked side of NSA started using heavier tactics like extortion, threats and financial incentives. The author, William Shirer and son in law of Joe McCarthy (William Tierney) were both close friends of Friedman but never disclosed that, as far as I know. Shirer almost killed himself because he thought nobody would read Rise and Fall of Third Reich; he was also an associate of NSA/Norris at Tribune. I am pleased to contest any difference between what I say and NSA official version, with perfect confidence. They probably they won't even try. You might see that I fill in the large blank spots in official history." "Don't ever think that NSA began in 1952. I've seen their charter and it isn't the public one. Until 1970, NSA considered themselves the real OSS and they were run until 1990 by about 10 military men most of whom were among the few who managed to fight back effectively on Dec 7, 1941. They considered NSA Directors and US Presidents to be hired help and figureheads. BTW, Elizebeth Smith Friedman was a cousin of Dan Quayle's wife."

Long Range Acoustic Devices are now used for crowd control along with other Directed Energy Weapons (DEW). Ultrasound is cyclic sound pressure with a frequency greater than the upper limit of human hearing. Although this limit varies from person to person, it is approximately 20 kilohertz (20,000 hertz) in healthy, young adults and thus, 20 kHz serves as a useful lower limit in describing ultrasound. The production of ultrasound is used in many different fields, typically to penetrate a medium and measure the reflection signature or supply focused energy. The reflection signature can reveal details about the inner structure of the medium, a property also used by animals such as bats for hunting. The most well known application of ultrasound is its use in sonography to produce pictures of foetuses in the human womb. There are a vast number of other applications as well.

Founding of NSA in Cryptoanalysis

DEAN OF CRYPTOLOGY - National Security Agency Bust of Friedman on display at the National Cryptologic Museum, where he is identified as the "Dean of American Cryptology". Following World War II, Friedman remained in government signals intelligence. In 1949 he became head of the cryptographic division of the newly-formed Armed Forces Security Agency (AFSA) and in 1952 became chief cryptologist for the National Security Agency (NSA) when it was formed to take over from AFSA. Friedman produced a classic series of textbooks, "Military Cryptanalysis", which was used to train NSA students. (These were revised and extended, under the title "Military Cryptanalytics", by Friedman's assistant and successor Lambros D. Callimahos, and used to train many additional cryptanalysts.) During his early years at NSA, he encouraged it to develop what was probably the first super-computers, although he was never convinced a machine could have the "insight" of a human mind.

Friedman retired in 1956 and, with his wife, turned his attention to the problem that had originally brought them together: examining Bacon's supposed codes. Together they wrote a book entitled The Cryptologist Looks at Shakespeare which won a prize from the Folger Library and was published under the title The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined. The book demonstrated flaws in Gallup's work and in that of others who sought hidden ciphers in Shakespeare's work.

At NSA's request Friedman prepared Six Lectures Concerning Cryptography and Cryptanalysis, which he delivered at NSA. But later the Agency, concerned about security, confiscated the reference materials from Friedman's home.

Friedman retired in 1956 and, with his wife, turned his attention to the problem that had originally brought them together: examining Bacon's supposed codes. Together they wrote a book entitled The Cryptologist Looks at Shakespeare which won a prize from the Folger Library and was published under the title The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined. The book demonstrated flaws in Gallup's work and in that of others who sought hidden ciphers in Shakespeare's work.

At NSA's request Friedman prepared Six Lectures Concerning Cryptography and Cryptanalysis, which he delivered at NSA. But later the Agency, concerned about security, confiscated the reference materials from Friedman's home.

TOP CODEBREAKERS

William Frederick Friedman (September 24, 1891 – November 12, 1969) was a US Army cryptographer who ran the research division of the Army's Signals Intelligence Service (SIS) in the 1930s, and parts of its follow-on services into the 1950s. In the late 1930s, subordinates of his led by Frank Rowlett broke Japan's PURPLE cipher, thus disclosing Japanese diplomatic secrets beginning before World War II era.

Another of Fabyan's pet projects was research into secret messages which Sir Francis Bacon had allegedly hidden in various texts during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. The research was carried out by Elizabeth Wells Gallup. She believed that she had discovered many such messages in the works of William Shakespeare, and convinced herself that Bacon had written many, if not all, of Shakespeare's works. Friedman had become something of an expert photographer while working on his other projects, and was asked to travel to England on several occasions to help Gallup photograph historical manuscripts during her research. He became fascinated with the work as he courted Elizebeth Smith, Mrs. Gallup's assistant and an accomplished cryptographer. They married, and he soon became director of Riverbank's Department of Codes and Ciphers as well as its Department of Genetics. During this time, Friedman wrote a series of 23 papers on cryptography, collectively known as the "Riverbank publications", included the first description of the index of coincidence, an important mathematical tool in cryptanalysis.

With the entry of the United States into World War I, Fabyan offered the services of his Department of Codes and Ciphers to the government. No Federal department existed for this kind of work (although both the Army and Navy had had embryonic departments at various times), and soon Riverbank became the unofficial cryptographic center for the US Government. During this period, the Friedmans broke a code used by German-funded Hindu radicals in the US who planned to ship arms to India to gain independence from Britain. Analyzing the format of the messages, Riverbank realized that the code was based on a dictionary of some sort, a cryptographic technique common at the time. The Friedmans soon managed to decrypt most of the messages, but only long after the case had come to trial did the book itself come to light: a German-English dictionary published in 1880.

Friedman turned out to be the true find. He fell in love with cryptographer Elizebeth Smith, and taught himself her specialty in a matter of weeks. He soon proved capable of cracking Britain's most sophisticated field code at a speed that was previously believed impossible. But as Friedman improved the code-breaking, Gallup's anticipated breakthrough on the authorship question failed to occur. The cryptanalysis simply didn't find anything useful and Friedman began to suspect that no cipher existed. After retirement, he and his wife returned to the Baconian ciphers. They proved false the Baconian theory in an incisive report that won them the Folger Shakespeare Library literary prize in 1955. This work was published in 1957 as "The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined."

The cryptology project might have dissolved had the United States not entered World War I in April 1917. The federal government had virtually no cryptographers, and Fabyan had plenty, so Riverbank became the NSA of its day. Newlyweds William and Elizebeth Friedman were soon cracking German and Mexican codes for the U.S. military and helping Scotland Yard expose anti-British agents in North America. When the U.S. Army finally established its own Cipher Bureau, its first 88 officers were trained by Fabyan and the Friedmans at Riverbank. When they graduated, William Friedman took a commission himself and went to France. William Friedman became the nation's top code breaker and led the successful effort to crack the Japanese codes before World War II. Elizebeth Friedman did her code breaking for the Coast Guard and the Treasury Department, and later established a secure communications system for the International Monetary Fund.

William Frederick Friedman (September 24, 1891 - November 12, 1969) served as a US Army cryptologist, running the research division of the Army's Signals Intelligence Service through the 1930s and its follow-on services right into the 1950s. He supervised the breaking of the Japanese Purple code in the late 1930s. Frank Rowlett led the SIS team which cracked the cypher machine. The output provided considerable information about Japanese diplomacy at the highest level througout World War II and afterwards, until Congressional hearings made public the fact that the US had been reading messages processed by that crypto system. Many consider Friedman one of the greatest cryptologists of all time, and his application of statistical methods to code-breaking one of the most significant advances in the field. He also coined much of the language used in decryption, introducing terms such as cryptography and cryptanalysis.

Friedman was born in Russia, the son of a postal worker who migrated to Pittsburgh in 1892. He studied at the Michigan Agricultural College in East Lansing and received a scholarship to work on genetics at Cornell University . Meanwhile George Fabyan, who ran a private research laboratory to study any project that caught his fancy, decided to set up his own genetics project and was referred to Friedman. Friedman joined Fabyan's Riverbank Laboratories outside Chicago in September 1915. As head of the Department of Genetics, one of the projects he ran studied the effects of moonlight on crop growth, and so he experimented with the planting of wheat during various phases of the moon.

Another of Fabyan's pet projects funded Elizabeth Wells Gallup's research into the coded messages which Sir Francis Bacon had allegedly hidden in various texts during the reign of Elizabeth I and King James. Believing that she had detected that many of Shakespeare's works also included such hidden messages, Gallup became convinced that Bacon wrote many, if not all, of William Shakespeare's works. Friedman had become something of an expert photographer while working on his other projects, and was asked to travel to England on several occasions to help Gallup photograph historical manuscripts during her research. At this point he became fascinated with cryptology, while he courted Elizebeth Smith, Mrs. Gallup's assistant and an accomplished cryptologist. They married, and soon after he became the director of the Department of Codes and Ciphers as well as of the Department of Genetics at Riverbank.

With the US's entry into World War I, Fabyan offered the services of his Department of Codes and Ciphers to the government. No Federal department existed for this kind of work (although both the Army and the Navy had had embryonic departments at various times), and soon Riverbank became the unofficial cryptographic center for the Federal GovernmentUS. During this period the Friedmans cracked a code used by German-funded Hindu radicals in the US who planned to ship arms to India to gain independence from Britain. Analysing the format of the messages, Riverbank realized that the code was based on a dictionary of some sort, a common encryption technique. The Friedmans soon managed to decode most messages, but only long after the case had come to trial did the book itself come to light: a German-English dictionary published in 1880.

The United States government decided to set up its own code-breaking service, and sent Army officers to Riverbank for training under Friedman. To support their training, Friedman produced a series of technical monographs, completing seven by early 1918. He then enlisted in the Army, and travelled to France to serve as the personal code-breaker for General John Pershing. He returned to the US in 1920 and published an eighth monograph, "The Index of Coincidence and its Applications in Cryptography", which is considered to be the most important single publication in modern cryptology to that time.

In 1921 he joined the government's American Black Chamber where he was placed in charge of researching new codes and ways to break them, and in 1922 he was promoted to head the Research and Development Division. After the dissolution of the Black Chamber in 1929, Friedman moved to the Army's Signals Intelligence Service (SIS) in a similar capacity.

During the 1920s a series of new cyphers processed by machines gained popularity, based largely on typewriter mechanicals attached to basic electrical circuitry - batteries, switches and lights. The first of such machines had been the Hebern Rotor Machine, designed in the US in 1915 by Edward Hebern. This system offered such security and simplicity of use that Hebern heavily promoted his company to investors, feeling that all companies would soon be using them and his company would clearly be successful. But the company went bankrupt when the war ended, and Hebern eventually landed in prison, convicted of stock manipulation.

Friedman realized that the new rotor machines would be important, and devoted some time to cracking Hebern's design. Over a period of years he discovered a number of problems common to most of the rotor machine designs. Examples of some dangerous features included having the rotors turn once with every keypress, and making the fast rotor (the one that turns with every keypress) at either end of the rotor stack. In this case the output generated by the machines will have strings of 26 letters that form a simple substitution cipher, and by collecting enough cyphertext and applying a standard statistical method known as the kappa test, he showed that he could, albeit with great difficulty, crack any code generated by such a machine.

Friedman then used his understanding of the rotor machines to develop several of his own that remained immune to his own attacks. He eventually developed nine designs, six of which remain still secret today. Some of his inventions while developing these systems only gained patents decades later, since the Defense Department regarded them as so critical that granting a patent would harm national security. The culmination of various earlier designs resulted in the SIGABA, which became the US's highest security encryption system during World War II. It was similar to the British Typex machine, and adapters were apparetnly built which could allow the two machines to interoperate. Neither was, as far as is publicly known, broken during WWII. In fact, SIGABA would still be quite good tady, in the computer era. computers.

In 1939 the Japanese introduced a new cypher machine system for their most secure diplomatic traffic to and from important embassies, replacing an earlier system SIS referred to as Red. The new cypher, referred to as Purple, proved quite difficult to crack. The Navy's OP-20-G and the SIS thought it might relate to the earlier mechanical cypher machines, and the SIS set about attacking it. After spending several months studying the cyphertexts and trying to discover the underlying patterns. Eventually, in an extraordianry achievement, the SIS team figured it out. Like the some of the prior Japanese designs, Purple didn't use 'rotors' unlike the German Enigma or the Hebern design, but used stepper switches like those used in automated telephone exchanges. Leo Rosen of the SIS built a machine and, astonishingly, used the same telephone stepper switch that the Japanese designer had used.

By the end of 1940 Friedman's team at the SIS had constructed an exact duplicate of the Purple machine, even though they had never seen one. With an understanding of Purple and duplicate machines of their own to use, the SIS could then decrypt an increasing amount of the Japanese traffic. One such intercept was the message to the Japanese Embassy in Washington ordering an end (on December 7th 1941) to the negotiations with the US. The message gave a clear indication of impending war, and was to have been delivered to the US State Department only hours prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The pressure of his responsibilites, including the Purple effort was too much and Friedman entered a hospital in 1941 with a nervous breakdown. After his release, he served as Director of Communications Research for the SIS for the rest of the war. Friedman visited the British code-breaking operations at the Government Code and Cipher School at Bletchley Park in 1941. He exchanged information on the techniques for attacking Purple for the British information on how they had broken the Enigma.

Following the WWII, Friedman remained in government signals intelligence. In 1949 he became head of the code division of the newly-formed Armed Forces Security Agency (AFSA), and in 1952 become the chief cryptologist for the National Security Agency (NSA) when it formed to take over from the AFSA.

Friedman retired in 1956 and turned his attention, with his wife, to the problem that had originally brought them together: examining Bacon's codes. In 1957 they wrote The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined, in which they demonstrated unfortunate flaws in Gallup's work. His health began to fail in the late 1960s, and he died in 1969.

Elizebeth Friedman was also heavily involved in cryptography throughout much of the inter-War period, although typically on the civilian side. During the 1920s she gained some fame for repeatedly breaking the cyphers and codes being used by "rum runners" bringing alcohol into the US during Prohibition, and in 1927 the US Coast Guard hired her to help them with their policing operations. By 1930 she had cracked over 12,000 messages for the Coast Guard, the Bureau of Customs, the Bureau of Narcotics, the Bureau of Prohibition, the Bureau of Internal Revenue, and the Department of Justice.

In 1934 she became involved in a particularly odd case, in which a Canadian-registered ship, the I'm Alone, sank after being chased into international waters off the US. She decoded several messages that demonstrated that a US citizen had actually paid for the ship, which therefore had ostensibe US-ownership. The result expanded the law regarding police chases, allowing a ship involved in illegal activity to be followed into international waters, and thereby extracting the US from an embarrassing political scandal.

During World War II Elizebeth Friedman moved to the OSS and became one of their chief cryptologists. She became involved in a particularly famous case in which a husband-and-wife team were sending coded messages to the Japanese, written on dolls that the wife sold through a thriving mail-order business. Velvalee Dickinson became known as "The Doll Woman" when the case was broken to the press. Elizebeth retired after her husband's death in 1969 and lived on until 1980.

* http://www.nsa.gov/honor/w_friedman.html

* http://www.sans.org/rr/history/friedman.php

In 1929, Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson withdrew the Bureau's funds, on the ground that "gentlemen do not read each other's mail." Yardley, jobless in the Depression, awoke America to the importance of cryptology in his best-selling The American Black Chamber (1931). His bureau's work was assumed by the army's tiny Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) under the brilliant cryptologist William F. Friedman. During World War I, Friedman, at the Riverbank Laboratories, a think tank near Chicago, had broken new paths for cryptanalysis; soon after he joined the War Department as a civilian employee in 1921, he reconstructed the locations and starting positions of the rotors in a cipher machine. His work placed the United States at the forefront of world cryptology.

Beginning in 1931, he expanded the SIS, hiring mathematicians first. By 1940, a team under the cryptanalyst Frank B. Rowlett had reconstructed the chief Japanese diplomatic cipher machine, which the Americans called purple. These solutions could not prevent Pearl Harbor because no messages saying anything like "We will attack Pearl Harbor" were ever transmitted; the Japanese diplomats themselves were not told of the attack. Later in the war, however, the solutions of the radiograms of the Japanese ambassador in Berlin, enciphered in purple, provided the Allies with what Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall called "our main basis of information regarding Hitler's intentions in Europe." One revealed details of Hitler's Atlantic Wall defenses.

The U.S. Navy's OP-20-G, established in 1924 under Lieutenant Laurence F. Safford, solved Japanese naval codes. This work flowered when the solutions of its branch in Hawaii made possible the American victory at Midway in 1942, the midair shootdown of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto in 1943, and the sinking of Japanese freighters throughout the Pacific war, strangling Japan. Its headquarters in Washington cooperated with the British code breaking agency, the Government Code and Cypher School, at Bletchley Park, northwest of London, to solve U-boat messages encrypted in the Enigma rotor cipher machine. This enabled Allied convoys to dodge wolf packs and so help win the Battle of the Atlantic. Teams of American cryptanalysts and tabulating machine engineers went to the British agency to cooperate in solving German Enigma and other cipher systems, shortening the land war in Europe. No other source of information— not spies, aerial photographs, or prisoner interrogations—provided such trustworthy, high-level, voluminous, detailed, and prompt intelligence as code breaking.

Wallace Clement Sabine (1868-1919)

Sabine's Reverberation Formula

Wallace Clement Sabine was a pioneer in architectural acoustics. A century ago he started experiments in the Fogg lecture room at Harvard, to investigate the impact of absorption on the reverberation time. It was on the 29th of October 1898 that he discovered the type of relation between these quantities. Sabine derived an expression for the duration T of the residual sound to decay below the audible intensity, starting from a 1,000,000 times higher initial intensity:

T = 0.161 V/A

where V is the room volume in cubic meters, and A is the total absorption in square meters. Sabine's reverberation formula has been applied successfully for many years to determine material absorption coefficients by means of reverberation rooms. Keeping in mind some conditions with regard to the sound field diffusion and the value of A, Sabine's formula is still widely accepted as a very useful estimation method for the reverberation time in rooms.

Sabin as Unit of Sound Absorption

The unit of sound absorption is square meter, referring to the area of open window. This unit stems from the fact that sound energy travelling toward an open window in a room will not be reflected at all, but completely disappear in the open air outside. The effect would be the same if the open window would be replaced with 100 % absorbing material of the same dimensions.

Therefore, 1 square meter of 100 % absorbing material has an absorption of 1 square meter of open window. In honor of W.C. Sabine, the unit of absorption is also named sabin or metric sabin. However, these units are used not very often. One sabin is the absorption of one square foot of open window, and one metric sabin is the absorption of one square meter of open window.

Symphony Hall

The first auditorium that was designed by Sabine, applying his new insight in acoustics, was the new Boston Music Hall, currently known as the Symphony Hall. It was formally opened on October 15, 1900. Nowadays, it is still considered one of the three finest concert halls in the world.

Another of Fabyan's pet projects was research into secret messages which Sir Francis Bacon had allegedly hidden in various texts during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. The research was carried out by Elizabeth Wells Gallup. She believed that she had discovered many such messages in the works of William Shakespeare, and convinced herself that Bacon had written many, if not all, of Shakespeare's works. Friedman had become something of an expert photographer while working on his other projects, and was asked to travel to England on several occasions to help Gallup photograph historical manuscripts during her research. He became fascinated with the work as he courted Elizebeth Smith, Mrs. Gallup's assistant and an accomplished cryptographer. They married, and he soon became director of Riverbank's Department of Codes and Ciphers as well as its Department of Genetics. During this time, Friedman wrote a series of 23 papers on cryptography, collectively known as the "Riverbank publications", included the first description of the index of coincidence, an important mathematical tool in cryptanalysis.

With the entry of the United States into World War I, Fabyan offered the services of his Department of Codes and Ciphers to the government. No Federal department existed for this kind of work (although both the Army and Navy had had embryonic departments at various times), and soon Riverbank became the unofficial cryptographic center for the US Government. During this period, the Friedmans broke a code used by German-funded Hindu radicals in the US who planned to ship arms to India to gain independence from Britain. Analyzing the format of the messages, Riverbank realized that the code was based on a dictionary of some sort, a cryptographic technique common at the time. The Friedmans soon managed to decrypt most of the messages, but only long after the case had come to trial did the book itself come to light: a German-English dictionary published in 1880.

Friedman turned out to be the true find. He fell in love with cryptographer Elizebeth Smith, and taught himself her specialty in a matter of weeks. He soon proved capable of cracking Britain's most sophisticated field code at a speed that was previously believed impossible. But as Friedman improved the code-breaking, Gallup's anticipated breakthrough on the authorship question failed to occur. The cryptanalysis simply didn't find anything useful and Friedman began to suspect that no cipher existed. After retirement, he and his wife returned to the Baconian ciphers. They proved false the Baconian theory in an incisive report that won them the Folger Shakespeare Library literary prize in 1955. This work was published in 1957 as "The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined."

The cryptology project might have dissolved had the United States not entered World War I in April 1917. The federal government had virtually no cryptographers, and Fabyan had plenty, so Riverbank became the NSA of its day. Newlyweds William and Elizebeth Friedman were soon cracking German and Mexican codes for the U.S. military and helping Scotland Yard expose anti-British agents in North America. When the U.S. Army finally established its own Cipher Bureau, its first 88 officers were trained by Fabyan and the Friedmans at Riverbank. When they graduated, William Friedman took a commission himself and went to France. William Friedman became the nation's top code breaker and led the successful effort to crack the Japanese codes before World War II. Elizebeth Friedman did her code breaking for the Coast Guard and the Treasury Department, and later established a secure communications system for the International Monetary Fund.

William Frederick Friedman (September 24, 1891 - November 12, 1969) served as a US Army cryptologist, running the research division of the Army's Signals Intelligence Service through the 1930s and its follow-on services right into the 1950s. He supervised the breaking of the Japanese Purple code in the late 1930s. Frank Rowlett led the SIS team which cracked the cypher machine. The output provided considerable information about Japanese diplomacy at the highest level througout World War II and afterwards, until Congressional hearings made public the fact that the US had been reading messages processed by that crypto system. Many consider Friedman one of the greatest cryptologists of all time, and his application of statistical methods to code-breaking one of the most significant advances in the field. He also coined much of the language used in decryption, introducing terms such as cryptography and cryptanalysis.

Friedman was born in Russia, the son of a postal worker who migrated to Pittsburgh in 1892. He studied at the Michigan Agricultural College in East Lansing and received a scholarship to work on genetics at Cornell University . Meanwhile George Fabyan, who ran a private research laboratory to study any project that caught his fancy, decided to set up his own genetics project and was referred to Friedman. Friedman joined Fabyan's Riverbank Laboratories outside Chicago in September 1915. As head of the Department of Genetics, one of the projects he ran studied the effects of moonlight on crop growth, and so he experimented with the planting of wheat during various phases of the moon.

Another of Fabyan's pet projects funded Elizabeth Wells Gallup's research into the coded messages which Sir Francis Bacon had allegedly hidden in various texts during the reign of Elizabeth I and King James. Believing that she had detected that many of Shakespeare's works also included such hidden messages, Gallup became convinced that Bacon wrote many, if not all, of William Shakespeare's works. Friedman had become something of an expert photographer while working on his other projects, and was asked to travel to England on several occasions to help Gallup photograph historical manuscripts during her research. At this point he became fascinated with cryptology, while he courted Elizebeth Smith, Mrs. Gallup's assistant and an accomplished cryptologist. They married, and soon after he became the director of the Department of Codes and Ciphers as well as of the Department of Genetics at Riverbank.

With the US's entry into World War I, Fabyan offered the services of his Department of Codes and Ciphers to the government. No Federal department existed for this kind of work (although both the Army and the Navy had had embryonic departments at various times), and soon Riverbank became the unofficial cryptographic center for the Federal GovernmentUS. During this period the Friedmans cracked a code used by German-funded Hindu radicals in the US who planned to ship arms to India to gain independence from Britain. Analysing the format of the messages, Riverbank realized that the code was based on a dictionary of some sort, a common encryption technique. The Friedmans soon managed to decode most messages, but only long after the case had come to trial did the book itself come to light: a German-English dictionary published in 1880.

The United States government decided to set up its own code-breaking service, and sent Army officers to Riverbank for training under Friedman. To support their training, Friedman produced a series of technical monographs, completing seven by early 1918. He then enlisted in the Army, and travelled to France to serve as the personal code-breaker for General John Pershing. He returned to the US in 1920 and published an eighth monograph, "The Index of Coincidence and its Applications in Cryptography", which is considered to be the most important single publication in modern cryptology to that time.

In 1921 he joined the government's American Black Chamber where he was placed in charge of researching new codes and ways to break them, and in 1922 he was promoted to head the Research and Development Division. After the dissolution of the Black Chamber in 1929, Friedman moved to the Army's Signals Intelligence Service (SIS) in a similar capacity.

During the 1920s a series of new cyphers processed by machines gained popularity, based largely on typewriter mechanicals attached to basic electrical circuitry - batteries, switches and lights. The first of such machines had been the Hebern Rotor Machine, designed in the US in 1915 by Edward Hebern. This system offered such security and simplicity of use that Hebern heavily promoted his company to investors, feeling that all companies would soon be using them and his company would clearly be successful. But the company went bankrupt when the war ended, and Hebern eventually landed in prison, convicted of stock manipulation.

Friedman realized that the new rotor machines would be important, and devoted some time to cracking Hebern's design. Over a period of years he discovered a number of problems common to most of the rotor machine designs. Examples of some dangerous features included having the rotors turn once with every keypress, and making the fast rotor (the one that turns with every keypress) at either end of the rotor stack. In this case the output generated by the machines will have strings of 26 letters that form a simple substitution cipher, and by collecting enough cyphertext and applying a standard statistical method known as the kappa test, he showed that he could, albeit with great difficulty, crack any code generated by such a machine.

Friedman then used his understanding of the rotor machines to develop several of his own that remained immune to his own attacks. He eventually developed nine designs, six of which remain still secret today. Some of his inventions while developing these systems only gained patents decades later, since the Defense Department regarded them as so critical that granting a patent would harm national security. The culmination of various earlier designs resulted in the SIGABA, which became the US's highest security encryption system during World War II. It was similar to the British Typex machine, and adapters were apparetnly built which could allow the two machines to interoperate. Neither was, as far as is publicly known, broken during WWII. In fact, SIGABA would still be quite good tady, in the computer era. computers.

In 1939 the Japanese introduced a new cypher machine system for their most secure diplomatic traffic to and from important embassies, replacing an earlier system SIS referred to as Red. The new cypher, referred to as Purple, proved quite difficult to crack. The Navy's OP-20-G and the SIS thought it might relate to the earlier mechanical cypher machines, and the SIS set about attacking it. After spending several months studying the cyphertexts and trying to discover the underlying patterns. Eventually, in an extraordianry achievement, the SIS team figured it out. Like the some of the prior Japanese designs, Purple didn't use 'rotors' unlike the German Enigma or the Hebern design, but used stepper switches like those used in automated telephone exchanges. Leo Rosen of the SIS built a machine and, astonishingly, used the same telephone stepper switch that the Japanese designer had used.