Proto-Britain

The Arguments for Atlantis

- 1 Great flood

- 2 Megafloods

- 2.1 The Black Sea (around 7,600 years ago)

- 2.2 The Caspian and Black Seas (around 16,000 years ago)

- 2.3 The lower Tigris-Euphrates Valley, reflooding the Persian Gulf (12,000 years ago)

- 2.4 Great Sunda wetlands, Indonesia

- 2.5 The Carpentaria plain (12,000 to 10,000 years ago)

- 2.6 The Aegean Basin

- 2.7 English Channel (Strait of Dover): Doggerland and the channel flood

- 2.8 Glacial lake outburst floods in North America

- 2.9 Holocene Impact-Generated Megatsunamis

- 2.10 The refilling of the Mediterranean Sea

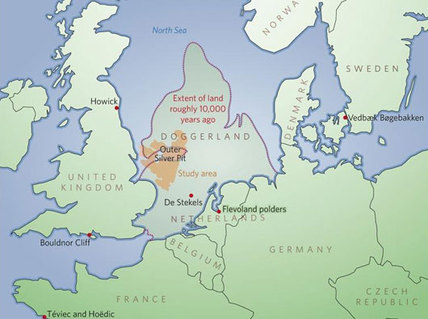

The flooding of the English Channel (Strait of Dover) is considered a flood of type 1. In 1998, the archaeologist B.J. Coles identified as "Doggerland" the now-drowned habitable and huntable lands in the coastal plain that was formed in the North Sea when sea level dropped. Doggerland has not caught the popular imagination, but the terrain was available for settlement. Its gentle swells remain as the Dogger Banks. Paleolithic reindeer hunters roamed the land; some traces of their encampments have been identified, but the timing of the submergence has not been fixed.[14] The region was watered by the glacial River Rhine, into which flowed the River Thames as a tributary; the combined river flowed into the North Sea, permitting access to Britain by large mammals and humans.

During an earlier glacial maximum, the combined rivers had been blocked to the north by an ice dam; they filled a vast lake with freshwater glacial melt on the bed of what is now the North Sea. A gently upfolding chalk ridge linking the Weald of Kent and Artois, perhaps some thirty metres higher than the current sea level, contained the glacial lake at the Strait of Dover. At a certain time, and apparently more than once, the barrier failed[15] or was overtopped, loosing a catastrophic flood that permanently separated Britain from the continent of Europe; a sonar study of the sea bed of the English Channel published in Nature, July 2007,[16] revealed the discovery of unmistakable marks of a megaflood on the English Channel seabed: deeply-eroded channels and braided features have left the remnants of streamlined islands among deeply gouged channels where the collapse occurred.[17]

(...) The mythical history of Ireland known as the Lebor Gabála Érenn, the Book of Invasions, says the Laigin were part of a confederation of tribes that settled in Ireland around 500 BCE. The Laigin, Domnainn and Gálioin were all survivors of a single group descended from the mythical Nemedians who were among the original inhabitants of Ireland after the flood (Geoffrey Keating places the Nemedian settlement of Ireland in approximately 5000 BCE). According to the version amended by Christian monks, Nemed was a direct descendant of Noah through Japheth and Magog, Noah's son and grandson. In their version of the Book of Invasions, Magog settled around the Russian Steppes in the kingdom of the Scythians. When the Nemedians fled Ireland after their defeat by the Fomorians, the branch which became known as the Laigin fled back to unspecified northern lands while those who became the Dommainn settled in Amorica and Britain and the branch called the Gálioin returned to the Mediterranean.

This relocation would be consistent with the theory that links the origin of the Cimmerians and the Scythians to the Baltic and indicates they retained close ties with the area. Marija Gimbutas believed the Cimmerians were the same people as the Sumerians, and traced their tribal name back to the Latvian root word for Northerners, Ziemeli, while the Welsh, originally the Cymri, also link their tribal name to the Cimmerians. Skaðin-awjo, the name for Scandinavia in the Nordic languages, can be translated as Island (*awjo) of the Scyths (Skaðin), referring either to the period before isostatic rebound raised the surrounding land and linked the island of Scandinavia to the European mainland at the end of the last Ice Age or to the period of flooding between 7200 BCE and 6000 BCE which coincided with the southern migrations. The 14th century Leabhar Breac , the Speckled Book, identifies the path of that migration by naming the boundaries of a mythical kingdom known as Lochlinn, saying that "it extended across the northern edge of the known world, from the Orkney Islands to Gothia (Poland/Ukraine) to Dacia (Romania) to the Maeotic Marsh (Sea of Azov) and the Rhipaean Mountains (Urals/Altai)".

Beneath the cold grey waves of the North Sea lies a lost landscape where vast herds of mammoth and bison roamed. This land was equal in size to modern Britain and contained hills and valleys, rivers and forests, marsh and moor. Sometimes warm and marshy and at other times a vast frozen tundra - now it is being systematically explored and already revealing evidence of early man. Was this Britain's Atlantis?

Sea Levels

At the height of the Ice Ages (and there were at least twenty!), sea levels were up to 300 ft lower than today. Just 8,000 years ago not only was much of the North Sea dry land, but so was the Irish Sea and the English Channel. In between these glaciations, the ice would melt and sea levels rise. Freed from the weight of ice, northern Britain began to rise while southern Britain began to sink - a process that continues today as the land tilt steepens. Long, dry raised beaches can be seen in Scotland, while more and more land is lost to the sea in the south and in the east. We make much of rising sea levels and global warming today, but consider the effects of massive amounts of water being released into the sea as the ice caps (covering much of the Northern Hemisphere) melted. Sea levels rose not by a foot or two, but by hundreds of feet.

Doggerland

The concept of a "land bridge" joining Britain to Europe is well known, but misleading. The term suggests a narrow causeway, but the reality was a vast lowland plain with the northern coastline stretching from Shetland to Jutland. The Thames flowed into the Rhine which turned south and made the English Channel its estuary. The highest point was a hilly region where the Dogger sand-banks are today. Recently, this has been called "Doggerland". Professor Bryony Coles of Exeter University is investigating the archaeology of "Doggerland" and an interesting map can be seen here. Evidence of this lost landscape has been plentiful for some time. Over the last 100 years, fishing boats and dredgers have recovered the tusks and bones of more than 50,000 mammoths! Did they live and die undisturbed or were they trapped on islands by rising waters as sea levels rose? We know that Mesolithic man hunted them because, in 1931 just off the Norfolk coast on the Leman and Ower banks, a fine, barbed harpoon of antler was recovered in a trawl net. It is 11,500 years old! Too valuable to have been carelessly lost, it seems likely that it was lodged in the body of a wounded animal that escaped the hunters to die elsewhere.

Tyneside

You can get a good idea of the submerged landscapes around Britain by looking at marine navigation charts of our coastal waters. On the charts, the depths and shoals will reveal the lost valleys and hills - you can also make out the courses of long lost rivers. More than 500 metres off the coast of Tyneside, scuba-diving archaeologists have found evidence of an undersea early Mesolithic settlement that could be 10,000 years old. Another more recent late Mesolithic site was found nearby. The finds included a flint arrowhead and cutting implements with serrated edges. Penny Spikins who is leading the international submerged prehistoric landscapes project said, "Archaeologists thought that the sites left by people who lived 5-10,000 years ago had simply been lost to the sea. But our finds could change our understanding of the earliest occupation of the British Isles. They open up a whole landscape under the water, a new frontier for archaeology."

Lost Lands

Low tides reveal submerged fossil forests off the coasts of Co. Wicklow in Ireland, the Isle of Wight, Dorset and Wales. Hartlepool's submerged forest is an SSSI and the area was covered in forest and peat bog in the Mesolithic. The 2,700-year-old skeleton of a Neolithic man was found buried in its peat in 1971. There is the enduring legend of the lost Cantreff of Gwaelod in Cardigan Bay and surely there must once have been extensive dry land beneath the treacherous sands of Morecambe Bay. There is a petrified forest in Mounts Bay, Cornwall with legends of an underwater city below the Seven Stones reef. Here, the legend of Lyonnesse is very strong and just twenty miles away are the Isles of Scilly. This is the best place to see the lost lands when at low tide, Bronze Age tombs, houses and field walls are revealed. Scilly was still one island in Roman times and only became an archipelago during the Tudor period. Other losses in Norfolk are the Roman Road across The Wash and Dunwich with its seven churches - one of the main ports of Medieval England.

Prehistoric Atlantis

With new underwater mapping and survey techniques, the story of Britain's "Prehistoric Atlantis" will be discovered. We shall not find the Lost Continent of Plato's Atlantis of course, but nevertheless there will be much to excite us. Close to shore there will be traces of Roman and Medieval settlements, while further out in the deeper water, the evidence will be harder to find. The hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic and Palaeolithic would have built any shelters of wood and possibly mammoth ivory (as in Siberia) so little trace will have survived. Speaking about the Tyneside discovery, Chief Archaeologist David Miles of English Heritage said "We know that there is a prehistoric Atlantis beneath the North Sea, where an area equal in size to Britain attached us to the continent. This discovery gives us a stepping stone into this unknown world."

Sea Levels

At the height of the Ice Ages (and there were at least twenty!), sea levels were up to 300 ft lower than today. Just 8,000 years ago not only was much of the North Sea dry land, but so was the Irish Sea and the English Channel. In between these glaciations, the ice would melt and sea levels rise. Freed from the weight of ice, northern Britain began to rise while southern Britain began to sink - a process that continues today as the land tilt steepens. Long, dry raised beaches can be seen in Scotland, while more and more land is lost to the sea in the south and in the east. We make much of rising sea levels and global warming today, but consider the effects of massive amounts of water being released into the sea as the ice caps (covering much of the Northern Hemisphere) melted. Sea levels rose not by a foot or two, but by hundreds of feet.

Doggerland

The concept of a "land bridge" joining Britain to Europe is well known, but misleading. The term suggests a narrow causeway, but the reality was a vast lowland plain with the northern coastline stretching from Shetland to Jutland. The Thames flowed into the Rhine which turned south and made the English Channel its estuary. The highest point was a hilly region where the Dogger sand-banks are today. Recently, this has been called "Doggerland". Professor Bryony Coles of Exeter University is investigating the archaeology of "Doggerland" and an interesting map can be seen here. Evidence of this lost landscape has been plentiful for some time. Over the last 100 years, fishing boats and dredgers have recovered the tusks and bones of more than 50,000 mammoths! Did they live and die undisturbed or were they trapped on islands by rising waters as sea levels rose? We know that Mesolithic man hunted them because, in 1931 just off the Norfolk coast on the Leman and Ower banks, a fine, barbed harpoon of antler was recovered in a trawl net. It is 11,500 years old! Too valuable to have been carelessly lost, it seems likely that it was lodged in the body of a wounded animal that escaped the hunters to die elsewhere.

Tyneside

You can get a good idea of the submerged landscapes around Britain by looking at marine navigation charts of our coastal waters. On the charts, the depths and shoals will reveal the lost valleys and hills - you can also make out the courses of long lost rivers. More than 500 metres off the coast of Tyneside, scuba-diving archaeologists have found evidence of an undersea early Mesolithic settlement that could be 10,000 years old. Another more recent late Mesolithic site was found nearby. The finds included a flint arrowhead and cutting implements with serrated edges. Penny Spikins who is leading the international submerged prehistoric landscapes project said, "Archaeologists thought that the sites left by people who lived 5-10,000 years ago had simply been lost to the sea. But our finds could change our understanding of the earliest occupation of the British Isles. They open up a whole landscape under the water, a new frontier for archaeology."

Lost Lands

Low tides reveal submerged fossil forests off the coasts of Co. Wicklow in Ireland, the Isle of Wight, Dorset and Wales. Hartlepool's submerged forest is an SSSI and the area was covered in forest and peat bog in the Mesolithic. The 2,700-year-old skeleton of a Neolithic man was found buried in its peat in 1971. There is the enduring legend of the lost Cantreff of Gwaelod in Cardigan Bay and surely there must once have been extensive dry land beneath the treacherous sands of Morecambe Bay. There is a petrified forest in Mounts Bay, Cornwall with legends of an underwater city below the Seven Stones reef. Here, the legend of Lyonnesse is very strong and just twenty miles away are the Isles of Scilly. This is the best place to see the lost lands when at low tide, Bronze Age tombs, houses and field walls are revealed. Scilly was still one island in Roman times and only became an archipelago during the Tudor period. Other losses in Norfolk are the Roman Road across The Wash and Dunwich with its seven churches - one of the main ports of Medieval England.

Prehistoric Atlantis

With new underwater mapping and survey techniques, the story of Britain's "Prehistoric Atlantis" will be discovered. We shall not find the Lost Continent of Plato's Atlantis of course, but nevertheless there will be much to excite us. Close to shore there will be traces of Roman and Medieval settlements, while further out in the deeper water, the evidence will be harder to find. The hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic and Palaeolithic would have built any shelters of wood and possibly mammoth ivory (as in Siberia) so little trace will have survived. Speaking about the Tyneside discovery, Chief Archaeologist David Miles of English Heritage said "We know that there is a prehistoric Atlantis beneath the North Sea, where an area equal in size to Britain attached us to the continent. This discovery gives us a stepping stone into this unknown world."

Pre-Diluvial Britain

Upper Paleolithic

A final ice age covered Britain between around 70,000 and 10,000 years ago with an extreme cold snap between 22,000 and 13,000 years ago called the Dimlington stadial (with the Last Glacial Maximum at around 20,000 years ago). This may well have driven humans south and out of Britain altogether, pushing them back across the land bridge that had resurfaced at the beginning of the glaciation, possibly to a refuge in Southern France and Iberia.

Holocene

By 9,500 years ago, the rising sea levels caused by the melting glaciers cut Britain off from Ireland and by around 6500 to 6000 BC continental Europe was cut off for the last time.[3] The warmer climate changed the Arctic environment to one of pine, birch and alder forest; this less open landscape was less conducive to the large herds of reindeer and wild horse that had previously sustained humans. Those animals were replaced in people's diets by pig and less social animals such as elk, red deer, roe deer, wild boar and aurochs (wild cattle) which would have required different hunting techniques.Humans spread and reached the far north of Scotland during this period. Sites from the British Mesolithic include the Mendips, Star Carr in Yorkshire and Oronsay in the Inner Hebrides.

Mesolithic

environment was of a bounteous nature, the rising population and ancient Britons' success in exploiting it eventually led to local exhaustion of many natural resources.

In 1997 DNA analysis was done on a tooth from a Mesolithic Cheddar Man from about 7150 BC whose remains were found in Gough's Cave at Cheddar Gorge. His mitochondrial DNA was of Haplogroup U5, a subclade of Haplogroup U (mtDNA) found in 11% of modern European populations.

The Neolithic (around 4000 – 2000 BC)

The Neolithic was the period of domestication of plants and animals. A debate is currently being waged between those who believe that the introduction of farming and a sedentary lifestyle was brought about by resident peoples adopting new practices, and those who hold the opinion that it was effected by continental invaders bringing their culture with them and, to some degree, replacing the indigenous populations.

Analysis of the mitochondrial DNA of modern European populations shows that over 80% are descended in the female line from European hunter-gatherers. Less than 20% are descended in the female line from Neolithic farmers from the Middle East and from subsequent migrations. The percentage in Britain is smaller at around 11% . Initial studies suggested that this situation is different with the paternal Y-chromosome DNA, varying from 10–100% across the country, being higher in the east. This was considered to show a large degree of population replacement during the Anglo-Saxon invasion and a nearly complete masking over of whatever population movement (or lack of it) went before in these two countries.[4] However, more widespread studies have suggested that there was less of a division between western and eastern parts of Britain with less Anglo-Saxon migration [5]. Looking from a more Europe-wide standpoint, researchers at Stanford University have found overlapping cultural and genetic evidence that supports the theory that migration was, at least, partially responsible for the Neolithic Revolution in Northern Europe (including Britain).[6] The science of genetic anthropology is changing very fast and a clear picture across the whole of human occupation of Britain has yet to emerge.[7]

The Bronze Age (around 2200 to 750 BC)

Main article: Bronze Age Britain This period can be sub-divided into an earlier phase (2300 to 1200) and a later one (1200 – 700). Beaker pottery appears in England around 2475–2315 cal BC[8] along with flat axes and burial practices of inhumation. With the revised Stonehenge chronology, this is after the Sarsen Circle and trilithons were erected at Stonehenge. Believed to be of Iberian origin, (modern day Spain and Portugal), Beaker techniques brought to Britain the skill of refining metal. At first the users made items from copper, but from around 2,150 BC smiths had discovered how to make bronze (which was much harder than copper) by mixing copper with a small amount of tin. With this discovery, the Bronze Age arrived in Britain. Over the next thousand years, bronze gradually replaced stone as the main material for tool and weapon making.

Britain had large, easily accessible reserves of tin in the modern areas of Cornwall and Devon in what is now southwest England, and thus tin mining began. By around 1,600 BC the southwest of Britain was experiencing a trade boom as British tin was exported across Europe, evidence of ports being found in southern Devon at Bantham and Mount Batten. Copper was mined at the Great Orme in North Wales.

The Beaker people were also skilled at making ornaments from gold, and examples of these have been found in graves of the wealthy Wessex culture of central southern Britain.

Early Bronze Age Britons buried their dead beneath earth mounds known as barrows, often with a beaker alongside the body. Later in the period, cremation was adopted as a burial practice with cemeteries of urns containing cremated individuals appearing in the archaeological record, with deposition of metal objects such as daggers. People of this period were also largely responsible for building many famous prehistoric sites such as the later phases of Stonehenge along with Seahenge. The Bronze Age people lived in round houses and divided up the landscape. Stone rows are to be seen on, for example, Dartmoor. They ate cattle, sheep, pigs and deer as well as shellfish and birds. They carried out salt manufacture. The wetlands were a source of wildfowl and reeds. There was ritual deposition of offerings in the wetlands and in holes in the ground. There was some debate amongst archaeologists as to whether the 'Beaker people' were a race of people who migrated to Britain en masse from the continent, or whether a prestigious Beaker cultural "package" of goods and behaviour (which eventually spread across most of western Europe) diffused to Britain's existing inhabitants through trade across tribal boundaries. Modern thinking tends towards the latter view. Alternatively, a ruling class of Beaker individuals may have made the migration and come to control the native population at some level. Genetics suggests that there was only a small infux of people to Britain at this time, around a few percent.

There is evidence of a relatively large scale disruption of cultural patterns which some scholars think may indicate an invasion (or at least a migration) into southern Great Britain circa the 12th century BC. This disruption was felt far beyond Britain, even beyond Europe, as most of the great Near Eastern empires collapsed (or experienced severe difficulties) and the Sea Peoples harried the entire Mediterranean basin around this time. Some scholars consider that the Celtic languages arrived in Britain at this time.

The Iron Age (around 750 BC – 43 AD)

Main article: British Iron Age In around 750 BC iron working techniques reached Britain from southern Europe. Iron was stronger and more plentiful than bronze, and its introduction marks the beginning of the Iron Age. Iron working revolutionised many aspects of life, most importantly agriculture. Iron tipped ploughs could churn up land far more quickly and deeply than older wooden or bronze ones, and iron axes could clear forest land far more efficiently for agriculture. There was a landscape of arable, pasture and managed woodland. There were many enclosed settlements and land ownership was important.

By 500 BC most people inhabiting the western British Isles were speaking some form of Insular Celtic. Among these people were skilled craftsmen who had begun producing intricately patterned gold jewellery, in addition to tools and weapons of both bronze and iron. It is disputed whether Iron Age Britons were "Celts", with some academics such as John Collis[15] and Simon James[16] actively opposing the idea of 'Celtic Britain', since the term was only applied at this time to a tribe in Gaul. However, placenames and tribal names from the later part of the period suggest that a Celtic language was spoken. The traveller Pytheas, whose own works are lost, was quoted by later classical authors as calling the people "Pretanni". The term "Celtic" continues to be used by linguists to describe the family that includes many of the ancient languages of Western Europe and modern British languages such as Welsh without controversy.[17]

Clovis-Age Comet Impact Theory

The Laurentian comet melted a vast tract of icesheet in North America, changing life in paleo-Britain forever. It unleashed a massive deluge of freshwater into the Atlantic. Six months is all it took to flip Europe’s climate from warm and sunny into the last ice age, researchers have found. They have discovered that the northern hemisphere was plunged into a big freeze 12,800 years ago by a sudden slowdown of the Gulf Stream that allowed ice to spread hundreds of miles southwards from the Arctic.“It would have been very sudden for those alive at the time,” said William Patterson, a geological sciences professor at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Canada, who carried out the research. “It would be the equivalent of taking Britain and moving it to the Arctic over the space of a few months.”

A 2010 study cites spikes of ammonium in Greenland ice cores as evidence for a giant comet impact at the end of the last ice age, and suggests that the collision may have caused a brief, final cold snap before the climate warmed up for good. In the April Geology, researchers describe finding chemical similarities in the cores between a layer corresponding to 1908, when a 50,000-metric-ton extraterrestrial object exploded over Tunguska, Siberia, and a deeper stratum dating to 12,900 years ago. They argue that the similarity is evidence that an object weighing as much as 50 billion metric tons triggered the Younger Dryas, a millennium-long cold spell that began just as the ice age was loosening its grip. Ammonium lingers as a sign of the cataclysmic event. (SN: 6/2/07, p. 339).

At the end of the Pleistocene about 10,000 years ago, there was an extinction event that decimated the large terrestrial mammalian herbivores and carnivores of North America, South America and Australia. In North America alone, more than thirty two genera of mammals became extinct…The cause of this extinction is debatable - R. W. Graham(Evolution of New Ecosystems at the End of the Pleistocene)

The world is unaware of the existence of prediluvian civilizations because they no longer exist. As the majority of myths and legends tell us, their continents were destroyed in a violent cataclysm. And this premise is now scientifically confirmable. Evidence exists to show that sometime between 10,000 and 13,500 years BC, our planet was wrecked by a natural cataclysm of unimaginable proportions. The devastating catastrophe was recorded by numerous tribes and nations. It is mentioned in the earliest Irish legends. Due to its disruptive geospheric effects, the earth suffered subsequent upheavals. Significant disasters (tsunamis, earthquakes, volcanoes) shook the world at 8,000, 6,000, and 3,000 years BC.

Nature's fury was particularly devastating to Britain and Scandinavia. These land were so smitten that they were through following ages referred to as "lands of the dead." So horrific was the onslaught, that the Western elders were, along with the aboriginal inhabitants of Britain and Scandinavia, forced to vacate their homelands for new habitations and territories in Europe and Asia. Wherever the elders traveled they were received as veritable gods. They, and their people, have been referred to by most historians as "Celts." They are, however, properly distinguished by the following more accurate titles: Aryans (Arya, Aryo, Ari, etc); Goths (Gots, Guts, Gets, etc) ; Nordics; Indo-Europeans; Caucasians.

The ancients decoded the skies and learned the conceptof time from that fundamental reference. There were many cycles and patterns to study -- Sun, Moon, planets, eclipses, solstices and Precession. Certain cycles of luminaries, planets, stars, and constellations may only be observed and noted from specific locations on earth.

To chart sidereal cycles a culture must be geographically stable for an extended period, like the Megalithic Irish and Nordic elders displaced to Europe and Asia from shattered Western habitats. They were the Hyperboreans or Atlanteans, and it was they and their descendants who were the world's first master astronomers, astrologers, geomancers, and cyclopean monument designers. The Gaels, Iberians, and Scythians, were descendants of these illustrious Megalithic ancestors. The primordial elders, the Druids, were members of the world's forgotten Stellar, Solar, and Lunar Cults. The current interglacial period has lasted about 10,000 years.

There is evidence Britain was inhabited 700,000 yrs ago. The oldest Northern European human evidence comes from Britain. Area the size of England was lost. http://www.proto-english.org/o2.html

A final ice age covered Britain between around 70,000 and 10,000 years ago with an extreme cold snap between 22,000 and 13,000 years ago called the Dimlington stadial (with the Last Glacial Maximum at around 20,000 years ago). This may well have driven humans south and out of Britain altogether, pushing them back across the land bridge that had resurfaced at the beginning of the glaciation, possibly to a refuge in Southern France and Iberia.

Holocene

By 9,500 years ago, the rising sea levels caused by the melting glaciers cut Britain off from Ireland and by around 6500 to 6000 BC continental Europe was cut off for the last time.[3] The warmer climate changed the Arctic environment to one of pine, birch and alder forest; this less open landscape was less conducive to the large herds of reindeer and wild horse that had previously sustained humans. Those animals were replaced in people's diets by pig and less social animals such as elk, red deer, roe deer, wild boar and aurochs (wild cattle) which would have required different hunting techniques.Humans spread and reached the far north of Scotland during this period. Sites from the British Mesolithic include the Mendips, Star Carr in Yorkshire and Oronsay in the Inner Hebrides.

Mesolithic

environment was of a bounteous nature, the rising population and ancient Britons' success in exploiting it eventually led to local exhaustion of many natural resources.

In 1997 DNA analysis was done on a tooth from a Mesolithic Cheddar Man from about 7150 BC whose remains were found in Gough's Cave at Cheddar Gorge. His mitochondrial DNA was of Haplogroup U5, a subclade of Haplogroup U (mtDNA) found in 11% of modern European populations.

The Neolithic (around 4000 – 2000 BC)

The Neolithic was the period of domestication of plants and animals. A debate is currently being waged between those who believe that the introduction of farming and a sedentary lifestyle was brought about by resident peoples adopting new practices, and those who hold the opinion that it was effected by continental invaders bringing their culture with them and, to some degree, replacing the indigenous populations.

Analysis of the mitochondrial DNA of modern European populations shows that over 80% are descended in the female line from European hunter-gatherers. Less than 20% are descended in the female line from Neolithic farmers from the Middle East and from subsequent migrations. The percentage in Britain is smaller at around 11% . Initial studies suggested that this situation is different with the paternal Y-chromosome DNA, varying from 10–100% across the country, being higher in the east. This was considered to show a large degree of population replacement during the Anglo-Saxon invasion and a nearly complete masking over of whatever population movement (or lack of it) went before in these two countries.[4] However, more widespread studies have suggested that there was less of a division between western and eastern parts of Britain with less Anglo-Saxon migration [5]. Looking from a more Europe-wide standpoint, researchers at Stanford University have found overlapping cultural and genetic evidence that supports the theory that migration was, at least, partially responsible for the Neolithic Revolution in Northern Europe (including Britain).[6] The science of genetic anthropology is changing very fast and a clear picture across the whole of human occupation of Britain has yet to emerge.[7]

The Bronze Age (around 2200 to 750 BC)

Main article: Bronze Age Britain This period can be sub-divided into an earlier phase (2300 to 1200) and a later one (1200 – 700). Beaker pottery appears in England around 2475–2315 cal BC[8] along with flat axes and burial practices of inhumation. With the revised Stonehenge chronology, this is after the Sarsen Circle and trilithons were erected at Stonehenge. Believed to be of Iberian origin, (modern day Spain and Portugal), Beaker techniques brought to Britain the skill of refining metal. At first the users made items from copper, but from around 2,150 BC smiths had discovered how to make bronze (which was much harder than copper) by mixing copper with a small amount of tin. With this discovery, the Bronze Age arrived in Britain. Over the next thousand years, bronze gradually replaced stone as the main material for tool and weapon making.

Britain had large, easily accessible reserves of tin in the modern areas of Cornwall and Devon in what is now southwest England, and thus tin mining began. By around 1,600 BC the southwest of Britain was experiencing a trade boom as British tin was exported across Europe, evidence of ports being found in southern Devon at Bantham and Mount Batten. Copper was mined at the Great Orme in North Wales.

The Beaker people were also skilled at making ornaments from gold, and examples of these have been found in graves of the wealthy Wessex culture of central southern Britain.

Early Bronze Age Britons buried their dead beneath earth mounds known as barrows, often with a beaker alongside the body. Later in the period, cremation was adopted as a burial practice with cemeteries of urns containing cremated individuals appearing in the archaeological record, with deposition of metal objects such as daggers. People of this period were also largely responsible for building many famous prehistoric sites such as the later phases of Stonehenge along with Seahenge. The Bronze Age people lived in round houses and divided up the landscape. Stone rows are to be seen on, for example, Dartmoor. They ate cattle, sheep, pigs and deer as well as shellfish and birds. They carried out salt manufacture. The wetlands were a source of wildfowl and reeds. There was ritual deposition of offerings in the wetlands and in holes in the ground. There was some debate amongst archaeologists as to whether the 'Beaker people' were a race of people who migrated to Britain en masse from the continent, or whether a prestigious Beaker cultural "package" of goods and behaviour (which eventually spread across most of western Europe) diffused to Britain's existing inhabitants through trade across tribal boundaries. Modern thinking tends towards the latter view. Alternatively, a ruling class of Beaker individuals may have made the migration and come to control the native population at some level. Genetics suggests that there was only a small infux of people to Britain at this time, around a few percent.

There is evidence of a relatively large scale disruption of cultural patterns which some scholars think may indicate an invasion (or at least a migration) into southern Great Britain circa the 12th century BC. This disruption was felt far beyond Britain, even beyond Europe, as most of the great Near Eastern empires collapsed (or experienced severe difficulties) and the Sea Peoples harried the entire Mediterranean basin around this time. Some scholars consider that the Celtic languages arrived in Britain at this time.

The Iron Age (around 750 BC – 43 AD)

Main article: British Iron Age In around 750 BC iron working techniques reached Britain from southern Europe. Iron was stronger and more plentiful than bronze, and its introduction marks the beginning of the Iron Age. Iron working revolutionised many aspects of life, most importantly agriculture. Iron tipped ploughs could churn up land far more quickly and deeply than older wooden or bronze ones, and iron axes could clear forest land far more efficiently for agriculture. There was a landscape of arable, pasture and managed woodland. There were many enclosed settlements and land ownership was important.

By 500 BC most people inhabiting the western British Isles were speaking some form of Insular Celtic. Among these people were skilled craftsmen who had begun producing intricately patterned gold jewellery, in addition to tools and weapons of both bronze and iron. It is disputed whether Iron Age Britons were "Celts", with some academics such as John Collis[15] and Simon James[16] actively opposing the idea of 'Celtic Britain', since the term was only applied at this time to a tribe in Gaul. However, placenames and tribal names from the later part of the period suggest that a Celtic language was spoken. The traveller Pytheas, whose own works are lost, was quoted by later classical authors as calling the people "Pretanni". The term "Celtic" continues to be used by linguists to describe the family that includes many of the ancient languages of Western Europe and modern British languages such as Welsh without controversy.[17]

Clovis-Age Comet Impact Theory

The Laurentian comet melted a vast tract of icesheet in North America, changing life in paleo-Britain forever. It unleashed a massive deluge of freshwater into the Atlantic. Six months is all it took to flip Europe’s climate from warm and sunny into the last ice age, researchers have found. They have discovered that the northern hemisphere was plunged into a big freeze 12,800 years ago by a sudden slowdown of the Gulf Stream that allowed ice to spread hundreds of miles southwards from the Arctic.“It would have been very sudden for those alive at the time,” said William Patterson, a geological sciences professor at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Canada, who carried out the research. “It would be the equivalent of taking Britain and moving it to the Arctic over the space of a few months.”

A 2010 study cites spikes of ammonium in Greenland ice cores as evidence for a giant comet impact at the end of the last ice age, and suggests that the collision may have caused a brief, final cold snap before the climate warmed up for good. In the April Geology, researchers describe finding chemical similarities in the cores between a layer corresponding to 1908, when a 50,000-metric-ton extraterrestrial object exploded over Tunguska, Siberia, and a deeper stratum dating to 12,900 years ago. They argue that the similarity is evidence that an object weighing as much as 50 billion metric tons triggered the Younger Dryas, a millennium-long cold spell that began just as the ice age was loosening its grip. Ammonium lingers as a sign of the cataclysmic event. (SN: 6/2/07, p. 339).

At the end of the Pleistocene about 10,000 years ago, there was an extinction event that decimated the large terrestrial mammalian herbivores and carnivores of North America, South America and Australia. In North America alone, more than thirty two genera of mammals became extinct…The cause of this extinction is debatable - R. W. Graham(Evolution of New Ecosystems at the End of the Pleistocene)

- A recent unexplained extinction event, the Pleistocene extinction which occurred at the end of the Ice Age.

- A recent massive change in climate and in the distribution of water on the earth with large scale changes in sea level, as happened with the end of the Ice Age.

- Evidence of mega or super floods released from the Continental Ice Sheets, found in a number of locations around the world.

- Evidence that there was a large comet impact event on the Laurentian Ice Sheet covering Northern Canada towards the end of the Ice Age that suddenly triggered super floods.

- Remains of marine life being found far inland and buried in late Ice Age glacial deposits such as the Michigan Whale bones and Marine Diatoms found in the Midwest.

- The occurrence of Marine relicts, living animals in fresh water far from the sea that have a recent marine history and Marine animals living in 'salty' lakes that are not part of the oceans today.

- Evidence of a sudden break in human society with old groups disappearing and being followed by a period of non occupation and then later being replaced by new groups, as happened with the Ice Age hunter gather groups whom disappeared with the Ice Age and are later replaced by farming societies after a period of abandonment at many sites.

The world is unaware of the existence of prediluvian civilizations because they no longer exist. As the majority of myths and legends tell us, their continents were destroyed in a violent cataclysm. And this premise is now scientifically confirmable. Evidence exists to show that sometime between 10,000 and 13,500 years BC, our planet was wrecked by a natural cataclysm of unimaginable proportions. The devastating catastrophe was recorded by numerous tribes and nations. It is mentioned in the earliest Irish legends. Due to its disruptive geospheric effects, the earth suffered subsequent upheavals. Significant disasters (tsunamis, earthquakes, volcanoes) shook the world at 8,000, 6,000, and 3,000 years BC.

Nature's fury was particularly devastating to Britain and Scandinavia. These land were so smitten that they were through following ages referred to as "lands of the dead." So horrific was the onslaught, that the Western elders were, along with the aboriginal inhabitants of Britain and Scandinavia, forced to vacate their homelands for new habitations and territories in Europe and Asia. Wherever the elders traveled they were received as veritable gods. They, and their people, have been referred to by most historians as "Celts." They are, however, properly distinguished by the following more accurate titles: Aryans (Arya, Aryo, Ari, etc); Goths (Gots, Guts, Gets, etc) ; Nordics; Indo-Europeans; Caucasians.

The ancients decoded the skies and learned the conceptof time from that fundamental reference. There were many cycles and patterns to study -- Sun, Moon, planets, eclipses, solstices and Precession. Certain cycles of luminaries, planets, stars, and constellations may only be observed and noted from specific locations on earth.

To chart sidereal cycles a culture must be geographically stable for an extended period, like the Megalithic Irish and Nordic elders displaced to Europe and Asia from shattered Western habitats. They were the Hyperboreans or Atlanteans, and it was they and their descendants who were the world's first master astronomers, astrologers, geomancers, and cyclopean monument designers. The Gaels, Iberians, and Scythians, were descendants of these illustrious Megalithic ancestors. The primordial elders, the Druids, were members of the world's forgotten Stellar, Solar, and Lunar Cults. The current interglacial period has lasted about 10,000 years.

There is evidence Britain was inhabited 700,000 yrs ago. The oldest Northern European human evidence comes from Britain. Area the size of England was lost. http://www.proto-english.org/o2.html

Scotland is the Lost City of Atlantis According to Comyns Beaumont's 19th century book Britain, the Key to World History, the Lost Civilisation of Atlantis is not in the Mediterranean, but right here in Scotland. His theory is complex and detailed, marrying the Bible with oral histories from around the world.

He looked at Homer, Plato and Heroditus as well as analysing "Flood Myths" around the world and came to the conclusion that Noah's flood and the catastrophic flooding that sunk Atlantis were one and the same.

Furthermore, Beaumont challenged the accepted placing of Atlantis. He maintained that Scotland was "the original domicile of the sons of Adam, who were the Titans or giants of classic fame as well as being the Atlanteans of Plato."

His theory is incredibly detailed but the main reasons for his conclusions are:

scotsman.com rating

2/10 - Beaumont gains two credibility points in recognition of the intricate research, inclusion of (possibly) verifiable land masses and overall for his stupendous turning around of known history, for example that far from outsiders populating Scotland after the big ice age, Scots (or Chaldeans, Phoenicians) actually left Scotland in the wake of the ice age/tsunami/disaster and populated the world. Awesome!

Read more: http://blogs.myspace.com/akpiper#ixzz15TWypYma

He looked at Homer, Plato and Heroditus as well as analysing "Flood Myths" around the world and came to the conclusion that Noah's flood and the catastrophic flooding that sunk Atlantis were one and the same.

Furthermore, Beaumont challenged the accepted placing of Atlantis. He maintained that Scotland was "the original domicile of the sons of Adam, who were the Titans or giants of classic fame as well as being the Atlanteans of Plato."

His theory is incredibly detailed but the main reasons for his conclusions are:

- There is no evidence of flooding in the Middle East.

- Geologists have found a massive lake under the Sea of Caithness – Shetland – possibly the one-time lagoon Lake Triton.

- In 584 BC land broke away from Norway causing a tsunami that submerged some of Scotland's east coast. This was, he claimed, the submerging of Atlantis.

- The Caledonian forest was home to boars, lions, bears and great white oxen called aurochs. A forest and these beasts are mentioned by Heroditus.

scotsman.com rating

2/10 - Beaumont gains two credibility points in recognition of the intricate research, inclusion of (possibly) verifiable land masses and overall for his stupendous turning around of known history, for example that far from outsiders populating Scotland after the big ice age, Scots (or Chaldeans, Phoenicians) actually left Scotland in the wake of the ice age/tsunami/disaster and populated the world. Awesome!

Read more: http://blogs.myspace.com/akpiper#ixzz15TWypYma

The Storegga Slide is the largest known Holocene-aged continental margin slope failure complex. It is estimated that 2400 to 3200 km3 of material moved down-slope during the last major slope failure, and although the slides occurred 7-8000 years ago the upper part of the complex has not come fully to rest yet. The Third (and last) Storegga Slide appears to have taken place shortly after the second slide – the slide that caused the tsunami featured in my previous post.

Cores from the floor of the Norwegian Basin reveal that a thick accumulation of more than 20 m of extremely well-sorted, homogeneous, very finegrained sediments covers the deepest portions of the basin. The uniform grain size indicates that extreme sediment sorting occurred during several hundred kilometres of transport to, and subsequent deposition in, the basin. The very fine grain size (3.1 ± 0.l µm) suggests that the unit was settled from suspension after the turbulent flow was over. Although the turbulent phase of the gravity flow that moved material out into the basin may have been brief (a question of days), significantly more time (years) is required for turbid sediments to settle from suspension and dewater and for the new sea floor to be colonized with a normal benthonic (bottom dwelling) fauna. Pore water sulphate concentrations within the uppermost 20 m of the event deposit are higher than those normally found in sea water. Apparently the impact of microbial sulphate reduction over the last ca. 8000 years since the re-deposition of these sediments has not been adequate to regenerate a typical sulphate gradient of decreasing concentration with sub-bottom depth. This observation suggests low rates of microbial reactions, which may be attributed to the refractory carbon composition in these re-deposited sediments.

(Actually, although microbial reactions are most intense soon after deposition they continue at slow rates within the sediments for millions of years, even though the organic carbon content and quality may be low)

The impact of the Storegga Slide event on the benthonic fauna within the Norwegian Basin must have been catastrophic. The effects would include massive death and destruction of the prior sea floor habitats during the turbulent phase of the flow. Rapid burial within a very thick layer would have made escape for any animal that happened to survive the initial phase of the event unlikely. The settling time required to deposit the observed event layer suggests that turbidity persisted for at least two years. During this prolonged period of extreme turbidity, the sediment water interface would have been very indistinct and this adverse environment would have precluded recolonization by most of the benthonic fauna existing before the slide.

All in all the recovery from the Storegga Slide event within the basin has thus been slow and pore water chemistry and sediment strength properties are still dominated by the disturbance 8000 years ago.

A final linguistic remark:

Storegga is Norwegian for "Great Edge", “stor” meaning great, big or large.

Reference:

Paull et al.

The tail of the Storegga Slide: insights from the geochemistry and sedimentology of the Norwegian Basin deposits

Sedimentology (2010) 57, 1409–1429

doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2010.01150

See also my earlier posts on the Storegga Slides:

The Storegga Submarine Landslide - and Tsunami

Storegga Tsunami Flooded Doggerland

No comments

Storegga Tsunami Flooded Doggerland Sunday, 3. October 2010, 18:23:10

submarine landslides, Sea level change, geology, tsunamis ...

Dogger Bank is a name I remember from when I was a teenager. It was regularly mentioned in a weather forecast especially for the fishers, broadcasted just before the morning news. Yes, on the radio, we had no TV when I was a teenager, which was back in the 1950's.

Dogger Bank is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea. It extends over approximately 17,600 km2. The water depth ranges from 15–36 m, about 20 m shallower than the surrounding sea. It is a productive fishing bank. The location of the Dogger Bank is marked with a red line in the following satellite image.

10,000 years ago, which means just after the latest glacial, or in other words the Early Holocene, the Dogger Bank was a range of hills in a land area covering a large part of what is now the southern North Sea. You could walk from Denmark or Germany to England – well you would have to cross a few rivers, of course, as there were no bridges – and archaeologists have documented that the land was populated. The archaeologists have named it “Doggerland”. I don't know how appropriate the name Doggerland is considering that “dogge” is an old Dutch word for fishing boat (better related to the fishing bank!). The following map shows the hypothetical extent of Doggerland about 10,000 years ago.

As sea levels rose after the end of the last glacial, and the level of the land sank due to isostatic adjustment after the Scandinavian ice cap had melted, Doggerland became submerged beneath the North Sea, cutting off what was previously the British peninsula from the European mainland around 8500 years ago. The Dogger Bank, which had been an upland area of Doggerland, is believed to have remained as an island until at least 7000 years ago.

I would like to highlight two events with special impacts on Doggerland.

First the drainage of the large North American glacial lake, Lake Agassiz. The catastrophic meltwater release from Lake Agassiz may have caused an abrupt 0.25–0.5m sea-level jump around 8300 years ago, and triggered the so-called ‘8200 calBP’ cold event around the Atlantic. This would have inundated a large part of Doggerland and furthermore it may have become unusually cold and windy on the remaining coasts of Doggerland.

Secondly the Storegga Slide Tsunami about 200 years later or around 8000 years ago, which would have had a catastrophic impact on the ontemporary coastal Mesolithic population. Following the Storegga Slide tsunami, it appears, Britain finally became separated from the continent and, in cultural terms, the Mesolithic there goes its own way.

The submarine Storegga landslide off the Norwegian coast is now usually described as three subsequent slides. The second of these generated a tsunami that apparently involved some 2400–3200 km3 of material that spread across the North Atlantic sea floor, altogether covering an area of around 95 000 km2. Traces of this tsunami have been identified in many regions in the North Atlantic, including Scotland, England and Denmark, but it also seems to have propagated as far as to the east coast of Greenland. The slide occurred at a time when the sea level in the southern North Sea stood about 17 m higher than the present level.

As we are talking about a coastal area Doggerland was probably relatively densely populated for that time – I am talking about near 1 inhabitant per km3. Maybe some 700 to 3000 individuals were affected. This does not necessarily imply that all were killed immediately, although given the likely rapidity and scale of the event, a significant number of people would almost certainly have been caught and drowned by the rapidly rising waters, while many others would have been displaced. The consequences would not have been limited to the wave’s immediate impact, as productive coastal areas could have been devastated, shellfish beds destroyed and covered by sands, together with any fixed fishing facilities, well-attested for the Late Mesolithic period. There are signs that the tsunami probably occurred during late autumn, so that any stored foods meant to last over the winter may also have been lost, with subsequent starvation among survivors. It is conceivable, particularly in the context of continuing rising sea-levels at this time, that the final abandonment of the remaining remnants of Doggerland as a place of permanent habitation by Mesolithic populations was brought about by the Storegga tsunami. Following the Storegga Slide tsunami, it appears, Britain finally became separated from the continent and, in cultural terms, the Mesolithic there goes its own way.

The following map, extensively cropped from Weninger et al. (2008), show the estimated coastlines around 9000 years ago (blue line) and around 8000 years ago (red line).

Just two final remarks:

1. Tsunamis can be extremely dangerous, and may occur in places, where they were never expected.

2. Sea level rise can be an extremely serious problem for coastal and island populations.

I am not selling this as the truth and nothing but the truth, but it does seem to fit rather well with the available data, and that is more or less what science is about - it remains a working hypothesis.

Cores from the floor of the Norwegian Basin reveal that a thick accumulation of more than 20 m of extremely well-sorted, homogeneous, very finegrained sediments covers the deepest portions of the basin. The uniform grain size indicates that extreme sediment sorting occurred during several hundred kilometres of transport to, and subsequent deposition in, the basin. The very fine grain size (3.1 ± 0.l µm) suggests that the unit was settled from suspension after the turbulent flow was over. Although the turbulent phase of the gravity flow that moved material out into the basin may have been brief (a question of days), significantly more time (years) is required for turbid sediments to settle from suspension and dewater and for the new sea floor to be colonized with a normal benthonic (bottom dwelling) fauna. Pore water sulphate concentrations within the uppermost 20 m of the event deposit are higher than those normally found in sea water. Apparently the impact of microbial sulphate reduction over the last ca. 8000 years since the re-deposition of these sediments has not been adequate to regenerate a typical sulphate gradient of decreasing concentration with sub-bottom depth. This observation suggests low rates of microbial reactions, which may be attributed to the refractory carbon composition in these re-deposited sediments.

(Actually, although microbial reactions are most intense soon after deposition they continue at slow rates within the sediments for millions of years, even though the organic carbon content and quality may be low)

The impact of the Storegga Slide event on the benthonic fauna within the Norwegian Basin must have been catastrophic. The effects would include massive death and destruction of the prior sea floor habitats during the turbulent phase of the flow. Rapid burial within a very thick layer would have made escape for any animal that happened to survive the initial phase of the event unlikely. The settling time required to deposit the observed event layer suggests that turbidity persisted for at least two years. During this prolonged period of extreme turbidity, the sediment water interface would have been very indistinct and this adverse environment would have precluded recolonization by most of the benthonic fauna existing before the slide.

All in all the recovery from the Storegga Slide event within the basin has thus been slow and pore water chemistry and sediment strength properties are still dominated by the disturbance 8000 years ago.

A final linguistic remark:

Storegga is Norwegian for "Great Edge", “stor” meaning great, big or large.

Reference:

Paull et al.

The tail of the Storegga Slide: insights from the geochemistry and sedimentology of the Norwegian Basin deposits

Sedimentology (2010) 57, 1409–1429

doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2010.01150

See also my earlier posts on the Storegga Slides:

The Storegga Submarine Landslide - and Tsunami

Storegga Tsunami Flooded Doggerland

No comments

Storegga Tsunami Flooded Doggerland Sunday, 3. October 2010, 18:23:10

submarine landslides, Sea level change, geology, tsunamis ...

Dogger Bank is a name I remember from when I was a teenager. It was regularly mentioned in a weather forecast especially for the fishers, broadcasted just before the morning news. Yes, on the radio, we had no TV when I was a teenager, which was back in the 1950's.

Dogger Bank is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea. It extends over approximately 17,600 km2. The water depth ranges from 15–36 m, about 20 m shallower than the surrounding sea. It is a productive fishing bank. The location of the Dogger Bank is marked with a red line in the following satellite image.

10,000 years ago, which means just after the latest glacial, or in other words the Early Holocene, the Dogger Bank was a range of hills in a land area covering a large part of what is now the southern North Sea. You could walk from Denmark or Germany to England – well you would have to cross a few rivers, of course, as there were no bridges – and archaeologists have documented that the land was populated. The archaeologists have named it “Doggerland”. I don't know how appropriate the name Doggerland is considering that “dogge” is an old Dutch word for fishing boat (better related to the fishing bank!). The following map shows the hypothetical extent of Doggerland about 10,000 years ago.

As sea levels rose after the end of the last glacial, and the level of the land sank due to isostatic adjustment after the Scandinavian ice cap had melted, Doggerland became submerged beneath the North Sea, cutting off what was previously the British peninsula from the European mainland around 8500 years ago. The Dogger Bank, which had been an upland area of Doggerland, is believed to have remained as an island until at least 7000 years ago.

I would like to highlight two events with special impacts on Doggerland.

First the drainage of the large North American glacial lake, Lake Agassiz. The catastrophic meltwater release from Lake Agassiz may have caused an abrupt 0.25–0.5m sea-level jump around 8300 years ago, and triggered the so-called ‘8200 calBP’ cold event around the Atlantic. This would have inundated a large part of Doggerland and furthermore it may have become unusually cold and windy on the remaining coasts of Doggerland.

Secondly the Storegga Slide Tsunami about 200 years later or around 8000 years ago, which would have had a catastrophic impact on the ontemporary coastal Mesolithic population. Following the Storegga Slide tsunami, it appears, Britain finally became separated from the continent and, in cultural terms, the Mesolithic there goes its own way.

The submarine Storegga landslide off the Norwegian coast is now usually described as three subsequent slides. The second of these generated a tsunami that apparently involved some 2400–3200 km3 of material that spread across the North Atlantic sea floor, altogether covering an area of around 95 000 km2. Traces of this tsunami have been identified in many regions in the North Atlantic, including Scotland, England and Denmark, but it also seems to have propagated as far as to the east coast of Greenland. The slide occurred at a time when the sea level in the southern North Sea stood about 17 m higher than the present level.

As we are talking about a coastal area Doggerland was probably relatively densely populated for that time – I am talking about near 1 inhabitant per km3. Maybe some 700 to 3000 individuals were affected. This does not necessarily imply that all were killed immediately, although given the likely rapidity and scale of the event, a significant number of people would almost certainly have been caught and drowned by the rapidly rising waters, while many others would have been displaced. The consequences would not have been limited to the wave’s immediate impact, as productive coastal areas could have been devastated, shellfish beds destroyed and covered by sands, together with any fixed fishing facilities, well-attested for the Late Mesolithic period. There are signs that the tsunami probably occurred during late autumn, so that any stored foods meant to last over the winter may also have been lost, with subsequent starvation among survivors. It is conceivable, particularly in the context of continuing rising sea-levels at this time, that the final abandonment of the remaining remnants of Doggerland as a place of permanent habitation by Mesolithic populations was brought about by the Storegga tsunami. Following the Storegga Slide tsunami, it appears, Britain finally became separated from the continent and, in cultural terms, the Mesolithic there goes its own way.

The following map, extensively cropped from Weninger et al. (2008), show the estimated coastlines around 9000 years ago (blue line) and around 8000 years ago (red line).

Just two final remarks:

1. Tsunamis can be extremely dangerous, and may occur in places, where they were never expected.

2. Sea level rise can be an extremely serious problem for coastal and island populations.

I am not selling this as the truth and nothing but the truth, but it does seem to fit rather well with the available data, and that is more or less what science is about - it remains a working hypothesis.

Megaflood Of 400,000 Years bp Made Britain An Island Jump to Comments Whilst the Mesolithic people living in the huntin’, shootin’ and fishin’ paradise that was Doggerland at the end of the last Ice Age, had little idea of the watery world it would one day become as Britain became cut off from mainland Europe, it’s improbable they realised that similar events had happened in their own distant past. This from BBC News, who describe one event at around 400,000 – 425,000 bp…

It is believed that hundreds of thousands of years ago, when ice sheets had pushed down from Scotland and Scandinavia, there existed a narrow isthmus linking Britain to continental Europe.This gently upfolding chalk ridge was perhaps some 30m higher than the current sea level in the English Channel.

Palaeo-researchers think it bounded a large lake to the northeast that was filled by glacial meltwaters fed by ancient versions of the rivers Thames and Rhine. Then – and they are not sure of the precise date – something happened to break the isthmus known as the Weald-Artois ridge.

“Possibly this was just the build-up of water behind. Possibly something triggered it; it’s well known today that there are small earthquakes in the Kent area,” explained Imperial’s Dr Jenny Collier. Either way, once the ridge was broken, the discharge would have been spectacular.

One can imagine the effect such a deluge would have had on anything living in its path – maybe there were a few archaic humans dotted here and there across the landscape, along with a suite of Pleistocene wildlife to accompany them – which if caught in the sudden release of countless millions of tons of water from the breached ridge would have been swept up and destroyed in the cataclysmic torrent.

At its peak, it is believed that the megaflood could have lasted several months, discharging an estimated one million cubic metres of water per second. And from the way some features have been cut, it is likely there were at least two distinct phases to the flooding.

“I was frankly astonished,” said Dr Collier. “I’ve worked in many exotic places around the world, including mid-ocean ridges where you see very spectacular features; and it was an enormous surprise to me that we should find something with a worldwide-scale implication offshore of the Isle of Wight. It was completely unexpected.”

The image at top is what’s exciting the researchers, as it appears that what we now know as the Dover Strait was effectively created by the huge flood gouging out the English Channel, and despite sea levels later lowering enough for land-bridges once more to connect Britain with continental Europe, the die was cast, and following another catastrophic event at 200,000 bp, described in Nature…

A second spill is likely to have occurred some 200,000 years later, during the most recent ice age, when again ice would have blocked up the north and created a lake where today’s North Sea lies. This flood was probably even more powerful than the first one, enlarging the Dover Strait to almost its present size. From then on, Britain would have been an island, only intermittently connected to the continent during times of extremely low sea level.

Dangerous floods are commonly associated with glaciation. But the surge of the English Channel was massively larger in size and impact than floods that occur fairly frequently in places such as the Himalayas today. “This was perhaps the biggest flood on Earth we have evidence for,” says (Philip) Gibbard, (a quaternary geologist at Cambridge University, UK)

And this isolation process looks only set to continue – if global climatic instability continues to raise sea-levels, more of Britain will disappear beneath the warmer waves of a wetter tomorrow, leaving perhaps only the highest hills and a few mountain-tops to give any indication that wide areas of dry land once abounded in the expanded North Sea of the future.

Update 20/07/07 – Cosmos Magazine have this – ‘Catastrophic Flood May Have Split Britain From Europe‘, in which they propose a date of 450,000 bp for the flood. Also worth reading for the perceived implications of the faunal and hominid populations that periodically entered into Britain over the course of hundreds of thousands of years.

It is believed that hundreds of thousands of years ago, when ice sheets had pushed down from Scotland and Scandinavia, there existed a narrow isthmus linking Britain to continental Europe.This gently upfolding chalk ridge was perhaps some 30m higher than the current sea level in the English Channel.

Palaeo-researchers think it bounded a large lake to the northeast that was filled by glacial meltwaters fed by ancient versions of the rivers Thames and Rhine. Then – and they are not sure of the precise date – something happened to break the isthmus known as the Weald-Artois ridge.

“Possibly this was just the build-up of water behind. Possibly something triggered it; it’s well known today that there are small earthquakes in the Kent area,” explained Imperial’s Dr Jenny Collier. Either way, once the ridge was broken, the discharge would have been spectacular.

One can imagine the effect such a deluge would have had on anything living in its path – maybe there were a few archaic humans dotted here and there across the landscape, along with a suite of Pleistocene wildlife to accompany them – which if caught in the sudden release of countless millions of tons of water from the breached ridge would have been swept up and destroyed in the cataclysmic torrent.

At its peak, it is believed that the megaflood could have lasted several months, discharging an estimated one million cubic metres of water per second. And from the way some features have been cut, it is likely there were at least two distinct phases to the flooding.

“I was frankly astonished,” said Dr Collier. “I’ve worked in many exotic places around the world, including mid-ocean ridges where you see very spectacular features; and it was an enormous surprise to me that we should find something with a worldwide-scale implication offshore of the Isle of Wight. It was completely unexpected.”

The image at top is what’s exciting the researchers, as it appears that what we now know as the Dover Strait was effectively created by the huge flood gouging out the English Channel, and despite sea levels later lowering enough for land-bridges once more to connect Britain with continental Europe, the die was cast, and following another catastrophic event at 200,000 bp, described in Nature…

A second spill is likely to have occurred some 200,000 years later, during the most recent ice age, when again ice would have blocked up the north and created a lake where today’s North Sea lies. This flood was probably even more powerful than the first one, enlarging the Dover Strait to almost its present size. From then on, Britain would have been an island, only intermittently connected to the continent during times of extremely low sea level.

Dangerous floods are commonly associated with glaciation. But the surge of the English Channel was massively larger in size and impact than floods that occur fairly frequently in places such as the Himalayas today. “This was perhaps the biggest flood on Earth we have evidence for,” says (Philip) Gibbard, (a quaternary geologist at Cambridge University, UK)

And this isolation process looks only set to continue – if global climatic instability continues to raise sea-levels, more of Britain will disappear beneath the warmer waves of a wetter tomorrow, leaving perhaps only the highest hills and a few mountain-tops to give any indication that wide areas of dry land once abounded in the expanded North Sea of the future.

Update 20/07/07 – Cosmos Magazine have this – ‘Catastrophic Flood May Have Split Britain From Europe‘, in which they propose a date of 450,000 bp for the flood. Also worth reading for the perceived implications of the faunal and hominid populations that periodically entered into Britain over the course of hundreds of thousands of years.