HOLLYWOOD HANGOVER:

Neon Nightlife Neverland

Bringing Yesterday's Future Back to the Present

With Memories of the Sixties Sunset Scene

Let the head-bashing begin!1965-1968

Whisky a GoGo, The Trip, The Troubadour, The Hullabaloo, Pandora's Box, Sea Witch, The Factory, Ciro's, etc.

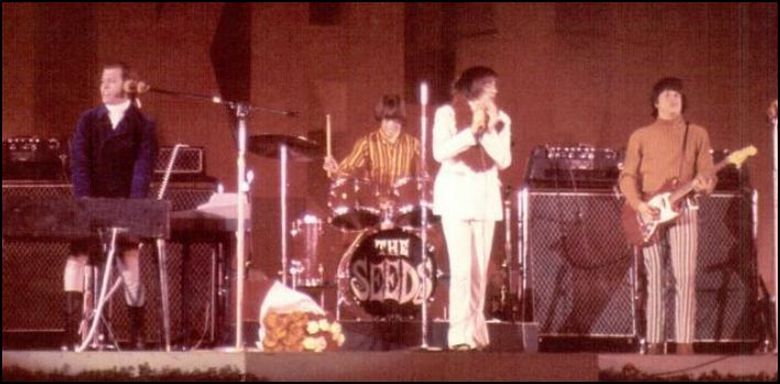

the Byrds, Love, the Leaves, Buffalo Springfield, the Seeds and the Doors

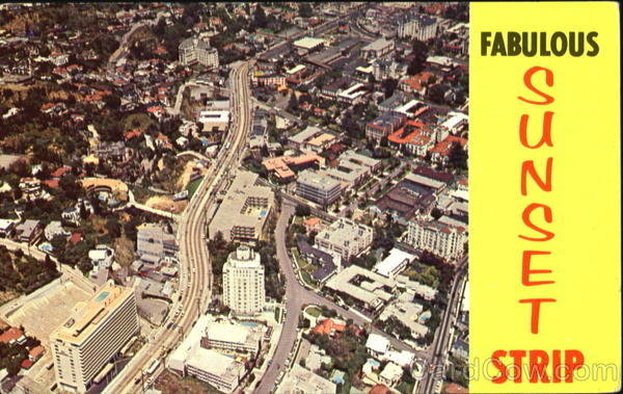

The Strip grew and reinvented itself, building on its own mythic aura, decade after decade, from the supper clubs of the '40s to the nightclubs of the '50s to the rock clubs of the '60s and Punk in the 70s and 80s.

This purest metaphor of L.A. was a mile of shameless sex and eccentric self-invention and rampaging capitalism.

Let the head-bashing begin!1965-1968

Whisky a GoGo, The Trip, The Troubadour, The Hullabaloo, Pandora's Box, Sea Witch, The Factory, Ciro's, etc.

the Byrds, Love, the Leaves, Buffalo Springfield, the Seeds and the Doors

The Strip grew and reinvented itself, building on its own mythic aura, decade after decade, from the supper clubs of the '40s to the nightclubs of the '50s to the rock clubs of the '60s and Punk in the 70s and 80s.

This purest metaphor of L.A. was a mile of shameless sex and eccentric self-invention and rampaging capitalism.

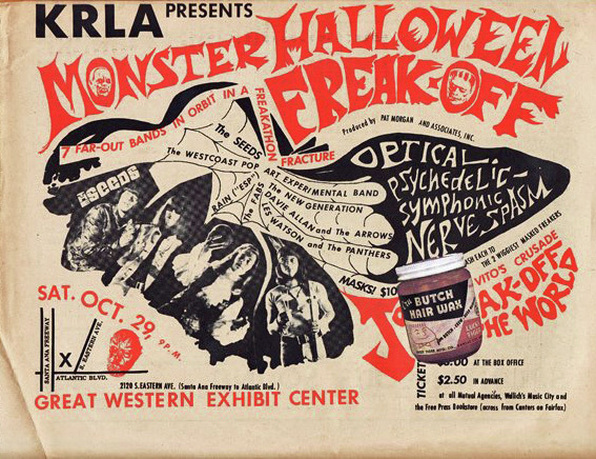

Whole KRLA BEAT PDF COLLECTION - http://krlabeat.sakionline.net/cgi-bin/index.cgi

|

|

|

Sculptor and dancer Vito Paulekas was the L.A. freak scene guru in the early sixties. Vito had a group of dancers

(that included Carl Franzoni) that danced & freaked out at the early Mothers' concerts.

(that included Carl Franzoni) that danced & freaked out at the early Mothers' concerts.

FANS, to FOLKIES to FREAKS

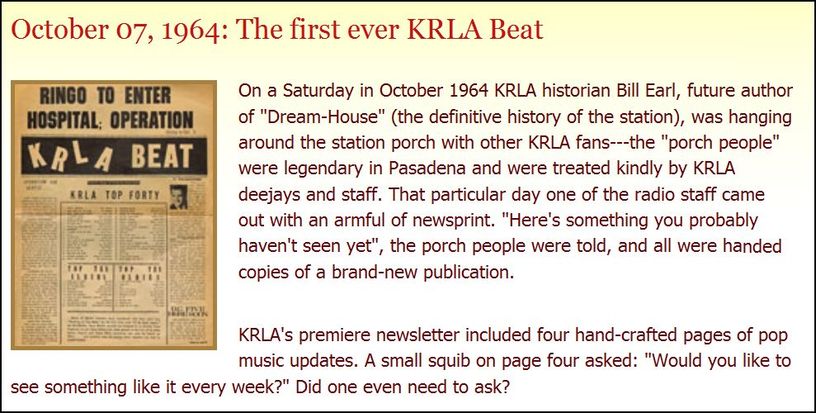

WE ARE THE PORCH-PEOPLE: 1965 Lots of English groups had plans to visit the Los Angeles area in early January 1965 for various TV or film appearances. KRLA which operated on the grounds of The Huntington Hotel in Pasadena became ground zero for promotions and fans. The Beat's report on The Beatles appears to have been written in December 1964 but held over for publication in the new year. Among expected visitors were The Hullabaloos (from Hull, hence the name), who were to appear on the "Ed Sullivan" variety show in late December. The Hullabaloos never did make it to the show but Ed was busy booking others, such as The Animals, The Dave Clark Five, Gerry and the Pacemakers, and Cilla Black, all of whom appeared on the show in the early months of 1965. The British Invasion was still going strong. Photos for this week include a selection of pictures from past issues of the KRLA Beat. Notable is a rare look at the Beatles' August 1964 press conference at the Cinnamon Cinder nightclub, owned by deejay Bob Eubanks. PDF size 2.7 MB. 4 pages. Vol. 0 No. 0.

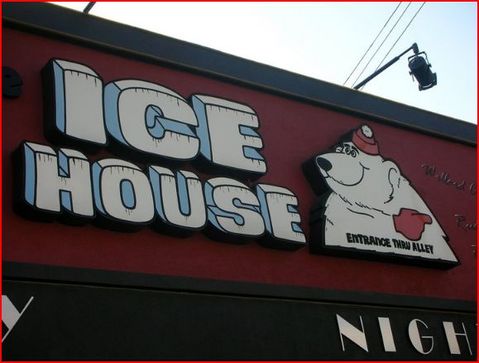

FOLK SCENE: Conceived by and opened in September 1960, by Pasadena businessman Willard Chilcott, THE ICE HOUSE has brought the finest in live entertainment to the San Gabriel Valley for over 42 years. During that time, over three million people have "discovered" the stars of today and tomorrow in our intimate showroom. In the 1960s, Folk music was in its prime, and The Ice House was America's top folk club with acts coming from all over the country to play and sing. Pasadena needed some music and comedy and The Ice House quickly became "the" place to go. The club combined music and comedy and gave audiences a consistently good time at reasonable prices. Notable acts included Kenny Rodgers, Linda Ronstadt, The Association, Seals and Crofts, Stephen Bishop, Jennifer Warnes, and hundreds more.

Hotel California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WILD IN THE STREETS

Warming Up for the 'Summer of Love'

Warming Up for the 'Summer of Love'

LA TEENAGE REBELLION: In the spring of 1961, Southern California suddenly erupted from the valleys to the beaches in angry generational conflict. There were 11 so called 'teen riots' in six months--three of them, including Griffith Park in May, Zuma Beach in June and Alhambra in October, involved thousands of youth. If largely forgotten today, at the time these confrontations generated worldwide headlines and national controversy. Despite the disparate sociological and geographical characteristics of the individual events, civic and law enforcement leaders conflated them as a single sustained outburst, an unprecedented insurrection against adult authority. And, following the causal chain back to El Cajon Boulevard the summer before, some of the country's leading anti-Communists once again discerned a conspiratorial pattern in youthful defiance. As Los Angeles' acting chief of police warned the nation, 'The eruption of violence and disorder directed at society's symbols of authority could be more devastating to America's hopes for the future than rockets and the 100-megaton bomb'.

REBELS WITHOUT A CLUE: Symbols of authority could be more devastating to America's hopes for the future than rockets and the 100-megaton bomb'.16 The first explosion occurred--according to subversive schedule?--on 1 May. Although national news was dominated by the huge 'Splash Day' riot in Galveston, Texas, where 800 youth were arrested, Los Angeles County sheriffs had to mount an amphibious landing to save the island resort of Avalon from its own teenage hordes. The city's third annual 'Buccaneer Ball' celebration was disrupted by hundreds of rowdy high school and college students who 'littered streets with beer cans and wine bottles, climbed over cars, trampled flower planters, ripped fire hoses and extinguishers from hotel walls and sprayed corridors'. Panicky local authorities called in deputies from the mainland who eventually arrested 57 of the 'mob'. The next weekend in Long Beach, in a fracas variously described in the local press as a 'riot' or 'near riot', 400 youths, 'all in bathing suits, swarmed out of the Bayshore Recreation Area...they halted cars on Bayshore Avenue and Ocean Boulevard, tussled with drivers, yanked out ignition keys and flung water-filled balloons'. When the police arrived, they too were jeered and bombarded with water balloons. Later, in sentencing one of the participants, a flustered municipal judge complained, 'I wish we had a whipping post. The youth of this country has absolutely no respect for authority. I just don't understand it'.

GRIFFITH PARK RIOT: The more significant Memorial Day (30 May) riot in Griffith Park was a direct, if unplanned, challenge by black youth to de facto segregation in Los Angeles public spaces. Although after the event the local Hearst paper, the Examiner, would sermonize that 'there is no segregation in the use of public facilities...[and] there is no Negro group of comparable size anywhere in the world, including the continent of Africa, which has available and unopposed the opportunities of the half million colored citizens of this region', this was nonsense.19 Faced with a radical shortage of parks and recreational facilities in south central Los Angeles, black residents, like Chicanos from the equally ghettoised Eastside, were systematically harassed by police when they attempted to freely enjoy Los Angeles's famed outdoor amenities. Only a small portion of the county beaches, for example, were integrated, and older folk recalled with bitterness how black residents had been burnt out of their homes by the Ku Klux Klan in several beach communities during the 1920s. Likewise Griffith Park, the city's largest public space, had an ugly history of racial exclusion which black youth had recently begun to challenge.

A major focus of contestation was the park's famed merry go round--a natural magnet to teenagers of all races. Blaming 'the publicity coming out of the South in connection with the Freedom Rides', Los Angeles police chief William Parker would later insinuate a black conspiracy to take over the merry go round area. 'We have been aware', he told the press, 'of a potential problem...for some time...[because] that part of the park has been pre-empted by Negroes for the last year'.20 On Memorial Day there was palpable tension as blacks arrived to find the LAPD deployed throughout the park. The riot erupted around 4pm when the carousel operator accused a teenager of boarding without paying. When the youth denied the allegation and refused to leave, he was wrestled to the ground by white police officers with billy clubs. The sight of the youth being violently pulled off the merry go round enraged the several thousand black picnickers in the vicinity. A teenage crowd followed the officers, surrounded the squad car and demanded the release of the prisoner. When he bolted from the car, all hell broke loose. One officer opened fire. The crowd replied with bottles. Five police were injured and forced to seek refuge in a park office. As LAPD reinforcements arrived with their sirens screaming, black teenagers shouted back, 'This is not Alabama'.

There were many cameras in the park that afternoon and images of the Griffith Park melee were soon reproduced around the world by the wire services. 'Aftermath of "Freedom Rides"?' was the caption that accompanied a sensational photograph in US News & World Report of hundreds of black youth rushing a policeman as he manhandled the original arrestee.22 There was a brief premonition in the media that as the freedom movement came northward into those ghettos of 'incomparable opportunity' (sic), non-violence might be left behind. Indeed Griffith Park symbolised the emergence of an audacious 'new breed', as James Brown would call them, ready to fight the police, if need be, to claim their civil rights. It was the first skirmish on the road to the Watts Rebellion four years later.

Yet while chief Parker was still fuming over 'Negro hoodlums', Gidget and 25,000 of her beach blanket friends were pelting sheriff's deputies and highway patrolmen with sand-packed beer cans. The weekend after the Griffith Park battle, Los Angeles' most popular rock and roll station invited listeners to a 'grunion derby' at Zuma Beach, near Malibu. KRLA expected about 2,000 to arrive on Saturday night--'instead 25,000, a conservative estimate, showed up'.23 County Parks and Recreation officials prevented the sponsors from erecting a planned dance floor and bandstand, so the huge crowd was left to organise its own amusements. At midnight, the official beach closing time, sheriffs ordered the revellers to leave. The response was a fierce fusillade of beer cans and bottles. Fifty additional patrol cars had to be called in before the crowd dispersed.24 Although KRLA disputed the hair raising accounts of mayhem and near rape promulgated by county officials, the general perception was that the deputies had narrowly prevented 'an uncontrolled riot of frightening proportions'. 'Only by great good fortune,' claimed the Los Angeles Examiner, 'the fracas did not result in fatalities'.

ROSEMEAD RIOTS: By any measure it was a busy night for the Los Angeles County sheriff's department. Some of the deputies speeding towards Zuma Beach were diverted instead to quell a second 'riot' in the blue collar San Gabriel Valley suburb of Rosemead. Several hundred teenagers--perhaps inflamed by radio reports about the Zuma melee--had gathered at the corner of Garvey and River Avenues and were reportedly stoning passing cars. Sheriffs arrested 47 juveniles on charges of rioting, battery and curfew violation. Meanwhile police in the south east industrial suburb of Bell were breaking up a street fight involving some 300 teenagers outside a wedding reception. Sheriff Peter Pitchess was at a loss to identify a root cause for these white riots. He could only observe that defiance of authority 'had moved beyond the point where blame can be placed solely on juveniles or adults, minority or majority groups'.

SAN GABRIEL RIOT: The next weekend (11 June) several deputies were slightly injured when they came to the aid of San Gabriel police attempting to enforce an archaic law against Sunday dancing at a local wedding celebration. Fifty officers battled with more than 300 teenagers and young adults outside a rented hall in Del Mar Avenue. At one point a policeman fired a warning shot in the air. Several of the rioters were charged with 'lynching' after they rescued a 17 year old from police custody. As temperatures of all kinds soared in July, the Los Angeles Times, conflating traditional street gangs and car clubs, worried that mobile teenage hoodlums now owned the streets.29 In response Sheriff Pitchess announced that his elite Special Enforcement Detail would be deployed to help regular deputies stringently enforce 10pm juvenile curfew ordinances throughout Los Angeles County. Local police departments followed suit in a massive regional crackdown on drive-ins, cruising strips, beach parking lots, and other nocturnal nodes of teenage culture.30

The law enforcement mobilisation seemed to work. After the lurid headlines of the early summer, Southern California survived without commotion a notorious Labour Day weekend that was celebrated across the east with fire hoses, police dogs and teargas. As headlines screamed 'Youth Mobs Riot In Five States; Hundreds Jailed', high school and college students ended the summer with major riots in Clermont (Indiana), Lake George (New York), Wildwood (New Jersey), Ocean City (Maryland), Falmouth and Hyannis (Massachusetts), and Hampton Beach (New Hampshire).31 But the Los Angeles area remained quiet...for a few days.

ALHAMBRA RIOT: October 61 - While some of their parents, on the advice of Leadabrand and Smith, were shopping for geiger counters, hundreds of carloads of teenagers were converging as they always did after Friday night football games (in this case 7 October) on their favorite Valley Boulevard drive-ins. Around midnight insults were exchanged beween the gloating victors (Monrovia High) and badly humiliated losers (Alhambra High), and the ensuing scuffle quickly grew into a 'whirlwind of fistfights that spread over a five block area', blocking traffic for four miles, east and west, along Valley Boulevard. From its mobile transmitter a local radio station broadcast a vivid blow by blow account of the donnybrook, which police claimed 'drew hundreds of others to the scene, all of them itching to join in the brawling'. While attempting to arrest a powerfully built youth whom they accused of 'mob raising', Alhambra police were themselves overwhelmed and roughed up. 'They were pushing and shoving,' reported the watch commander, 'attempting to grab guns from officers' holsters, jerking off their hats, jumping on their backs and trying to knock them to the ground.' Alhambra's desperate '999' (code for riot) appeal was answered by more than 100 police and sheriffs from other jurisdictions. They blockaded access to Valley Boulevard and ordered the estimated 1,000 to 1,200 rioters--including Chicano as well as white youth--to disperse. The common response was, 'Go to hell.' After an hour of further melee 31 young adults and 60 juveniles were in custody. It was officially characterised as 'one of the worst examples of civil disobedience' in Los Angeles County since the 1943 'Zoot suit' riots.

REBELS WITHOUT A CLUE: Symbols of authority could be more devastating to America's hopes for the future than rockets and the 100-megaton bomb'.16 The first explosion occurred--according to subversive schedule?--on 1 May. Although national news was dominated by the huge 'Splash Day' riot in Galveston, Texas, where 800 youth were arrested, Los Angeles County sheriffs had to mount an amphibious landing to save the island resort of Avalon from its own teenage hordes. The city's third annual 'Buccaneer Ball' celebration was disrupted by hundreds of rowdy high school and college students who 'littered streets with beer cans and wine bottles, climbed over cars, trampled flower planters, ripped fire hoses and extinguishers from hotel walls and sprayed corridors'. Panicky local authorities called in deputies from the mainland who eventually arrested 57 of the 'mob'. The next weekend in Long Beach, in a fracas variously described in the local press as a 'riot' or 'near riot', 400 youths, 'all in bathing suits, swarmed out of the Bayshore Recreation Area...they halted cars on Bayshore Avenue and Ocean Boulevard, tussled with drivers, yanked out ignition keys and flung water-filled balloons'. When the police arrived, they too were jeered and bombarded with water balloons. Later, in sentencing one of the participants, a flustered municipal judge complained, 'I wish we had a whipping post. The youth of this country has absolutely no respect for authority. I just don't understand it'.

GRIFFITH PARK RIOT: The more significant Memorial Day (30 May) riot in Griffith Park was a direct, if unplanned, challenge by black youth to de facto segregation in Los Angeles public spaces. Although after the event the local Hearst paper, the Examiner, would sermonize that 'there is no segregation in the use of public facilities...[and] there is no Negro group of comparable size anywhere in the world, including the continent of Africa, which has available and unopposed the opportunities of the half million colored citizens of this region', this was nonsense.19 Faced with a radical shortage of parks and recreational facilities in south central Los Angeles, black residents, like Chicanos from the equally ghettoised Eastside, were systematically harassed by police when they attempted to freely enjoy Los Angeles's famed outdoor amenities. Only a small portion of the county beaches, for example, were integrated, and older folk recalled with bitterness how black residents had been burnt out of their homes by the Ku Klux Klan in several beach communities during the 1920s. Likewise Griffith Park, the city's largest public space, had an ugly history of racial exclusion which black youth had recently begun to challenge.

A major focus of contestation was the park's famed merry go round--a natural magnet to teenagers of all races. Blaming 'the publicity coming out of the South in connection with the Freedom Rides', Los Angeles police chief William Parker would later insinuate a black conspiracy to take over the merry go round area. 'We have been aware', he told the press, 'of a potential problem...for some time...[because] that part of the park has been pre-empted by Negroes for the last year'.20 On Memorial Day there was palpable tension as blacks arrived to find the LAPD deployed throughout the park. The riot erupted around 4pm when the carousel operator accused a teenager of boarding without paying. When the youth denied the allegation and refused to leave, he was wrestled to the ground by white police officers with billy clubs. The sight of the youth being violently pulled off the merry go round enraged the several thousand black picnickers in the vicinity. A teenage crowd followed the officers, surrounded the squad car and demanded the release of the prisoner. When he bolted from the car, all hell broke loose. One officer opened fire. The crowd replied with bottles. Five police were injured and forced to seek refuge in a park office. As LAPD reinforcements arrived with their sirens screaming, black teenagers shouted back, 'This is not Alabama'.

There were many cameras in the park that afternoon and images of the Griffith Park melee were soon reproduced around the world by the wire services. 'Aftermath of "Freedom Rides"?' was the caption that accompanied a sensational photograph in US News & World Report of hundreds of black youth rushing a policeman as he manhandled the original arrestee.22 There was a brief premonition in the media that as the freedom movement came northward into those ghettos of 'incomparable opportunity' (sic), non-violence might be left behind. Indeed Griffith Park symbolised the emergence of an audacious 'new breed', as James Brown would call them, ready to fight the police, if need be, to claim their civil rights. It was the first skirmish on the road to the Watts Rebellion four years later.

Yet while chief Parker was still fuming over 'Negro hoodlums', Gidget and 25,000 of her beach blanket friends were pelting sheriff's deputies and highway patrolmen with sand-packed beer cans. The weekend after the Griffith Park battle, Los Angeles' most popular rock and roll station invited listeners to a 'grunion derby' at Zuma Beach, near Malibu. KRLA expected about 2,000 to arrive on Saturday night--'instead 25,000, a conservative estimate, showed up'.23 County Parks and Recreation officials prevented the sponsors from erecting a planned dance floor and bandstand, so the huge crowd was left to organise its own amusements. At midnight, the official beach closing time, sheriffs ordered the revellers to leave. The response was a fierce fusillade of beer cans and bottles. Fifty additional patrol cars had to be called in before the crowd dispersed.24 Although KRLA disputed the hair raising accounts of mayhem and near rape promulgated by county officials, the general perception was that the deputies had narrowly prevented 'an uncontrolled riot of frightening proportions'. 'Only by great good fortune,' claimed the Los Angeles Examiner, 'the fracas did not result in fatalities'.

ROSEMEAD RIOTS: By any measure it was a busy night for the Los Angeles County sheriff's department. Some of the deputies speeding towards Zuma Beach were diverted instead to quell a second 'riot' in the blue collar San Gabriel Valley suburb of Rosemead. Several hundred teenagers--perhaps inflamed by radio reports about the Zuma melee--had gathered at the corner of Garvey and River Avenues and were reportedly stoning passing cars. Sheriffs arrested 47 juveniles on charges of rioting, battery and curfew violation. Meanwhile police in the south east industrial suburb of Bell were breaking up a street fight involving some 300 teenagers outside a wedding reception. Sheriff Peter Pitchess was at a loss to identify a root cause for these white riots. He could only observe that defiance of authority 'had moved beyond the point where blame can be placed solely on juveniles or adults, minority or majority groups'.

SAN GABRIEL RIOT: The next weekend (11 June) several deputies were slightly injured when they came to the aid of San Gabriel police attempting to enforce an archaic law against Sunday dancing at a local wedding celebration. Fifty officers battled with more than 300 teenagers and young adults outside a rented hall in Del Mar Avenue. At one point a policeman fired a warning shot in the air. Several of the rioters were charged with 'lynching' after they rescued a 17 year old from police custody. As temperatures of all kinds soared in July, the Los Angeles Times, conflating traditional street gangs and car clubs, worried that mobile teenage hoodlums now owned the streets.29 In response Sheriff Pitchess announced that his elite Special Enforcement Detail would be deployed to help regular deputies stringently enforce 10pm juvenile curfew ordinances throughout Los Angeles County. Local police departments followed suit in a massive regional crackdown on drive-ins, cruising strips, beach parking lots, and other nocturnal nodes of teenage culture.30

The law enforcement mobilisation seemed to work. After the lurid headlines of the early summer, Southern California survived without commotion a notorious Labour Day weekend that was celebrated across the east with fire hoses, police dogs and teargas. As headlines screamed 'Youth Mobs Riot In Five States; Hundreds Jailed', high school and college students ended the summer with major riots in Clermont (Indiana), Lake George (New York), Wildwood (New Jersey), Ocean City (Maryland), Falmouth and Hyannis (Massachusetts), and Hampton Beach (New Hampshire).31 But the Los Angeles area remained quiet...for a few days.

ALHAMBRA RIOT: October 61 - While some of their parents, on the advice of Leadabrand and Smith, were shopping for geiger counters, hundreds of carloads of teenagers were converging as they always did after Friday night football games (in this case 7 October) on their favorite Valley Boulevard drive-ins. Around midnight insults were exchanged beween the gloating victors (Monrovia High) and badly humiliated losers (Alhambra High), and the ensuing scuffle quickly grew into a 'whirlwind of fistfights that spread over a five block area', blocking traffic for four miles, east and west, along Valley Boulevard. From its mobile transmitter a local radio station broadcast a vivid blow by blow account of the donnybrook, which police claimed 'drew hundreds of others to the scene, all of them itching to join in the brawling'. While attempting to arrest a powerfully built youth whom they accused of 'mob raising', Alhambra police were themselves overwhelmed and roughed up. 'They were pushing and shoving,' reported the watch commander, 'attempting to grab guns from officers' holsters, jerking off their hats, jumping on their backs and trying to knock them to the ground.' Alhambra's desperate '999' (code for riot) appeal was answered by more than 100 police and sheriffs from other jurisdictions. They blockaded access to Valley Boulevard and ordered the estimated 1,000 to 1,200 rioters--including Chicano as well as white youth--to disperse. The common response was, 'Go to hell.' After an hour of further melee 31 young adults and 60 juveniles were in custody. It was officially characterised as 'one of the worst examples of civil disobedience' in Los Angeles County since the 1943 'Zoot suit' riots.

FROM SUNSET SANCTUARY TO BATTLEGROUND

The story of Sunset nightlife preceeds the 60s, but Hollywood entertainers abandoned the strip for a lively mobbed up Vegas scene, leaving their rock and roll children to take over where they had left off. At some point in the mid 1960s, the kids started hanging around on Sunset Strip, which at the time was still home to many of the restaurants that once boasted famous Hollywood patrons. To curtail the invading counterculture, the city imposed a strict curfew, and cops clashed with longhairs in a series of small riots that galvanized the hippies rather than dispersed them.

The skirmishes inspired Buffalo Springfield to write "For What It's Worth" and Four-Leaf Productions to bankroll the teensploitation flick Riot on Sunset Strip, featuring a theme song by local group the Standells. It begins mundanely enough: "I'm going down to the Strip tonight, I'm not on a stay-home trip tonight," sings drummer Dick Dodd over Tony Valentino's snarling guitar lick. But the song's hard beat is more of a billy-club swing than a hip shake, and the lyrics become increasingly serious, as he laments the Strip has become "just a place for black-and-white cars to race. It's causin' a riot!" More pointed and angry than the square film that bears it title, the song depicts Los Angeles as a tensed city on the brink of chaos and violence, and the Standells could just as well have been singing about Watts or any of the race riots that made the curfew clashes seem polite and placid by comparison.

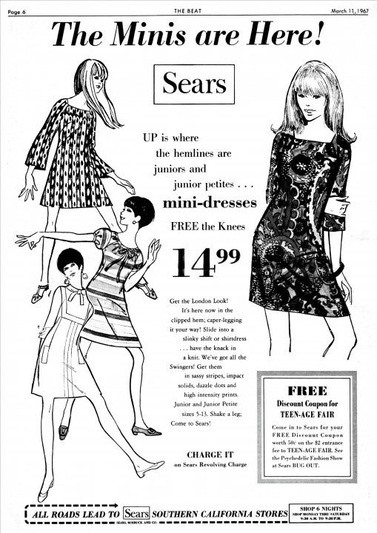

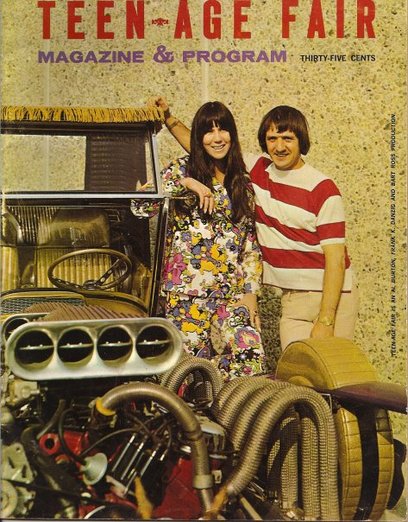

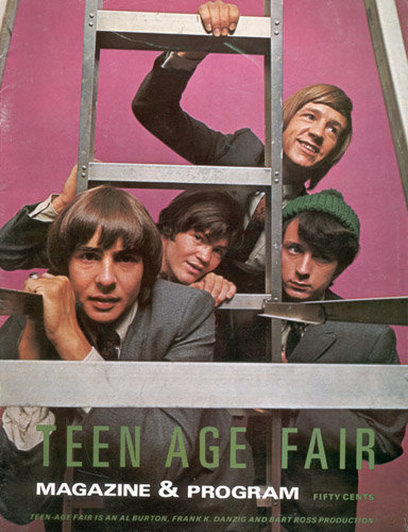

In 1965 the County reluctantly acceded to club-owners' and record companies' pleas and created a tiered licensing system that allowed 18-to-21-year-olds inside clubs where alcohol was served, while creating special liquor-less music venues for younger 15-to-18-year-olds. The youth club scene promptly exploded. From the moment the Byrds debuted at Ciro’s on March 26th 1965 — with Bob Dylan joining them on stage — through the demonstrations of November 1966, Sunset Strip nightclubs introduced the Doors, Buffalo Springfield the Mothers of Invention, and so many more.

This legendary Battle of the Strip, 1966–1968, was only the most celebrated episode in the struggle of teenagers of all colours during the 1960s and 1970s to create their own realm of freedom and carnivalesque sociality within the Southern California night. There were other memorable contests with business and police over Griffith Park 'love-ins', beach parties, interracial concerts, counter-cultural neighbourhoods (like Venice Beach), 'head' shopping districts (like L.A.'s Haight-Ashbury on Fairfax), cruising strips (Whittier, Hollywood, and Van Nuys boulevards), street-racing locales, and the myriad local hangouts where kids quietly or brazenly defied parents, police, and curfews.

The skirmishes inspired Buffalo Springfield to write "For What It's Worth" and Four-Leaf Productions to bankroll the teensploitation flick Riot on Sunset Strip, featuring a theme song by local group the Standells. It begins mundanely enough: "I'm going down to the Strip tonight, I'm not on a stay-home trip tonight," sings drummer Dick Dodd over Tony Valentino's snarling guitar lick. But the song's hard beat is more of a billy-club swing than a hip shake, and the lyrics become increasingly serious, as he laments the Strip has become "just a place for black-and-white cars to race. It's causin' a riot!" More pointed and angry than the square film that bears it title, the song depicts Los Angeles as a tensed city on the brink of chaos and violence, and the Standells could just as well have been singing about Watts or any of the race riots that made the curfew clashes seem polite and placid by comparison.

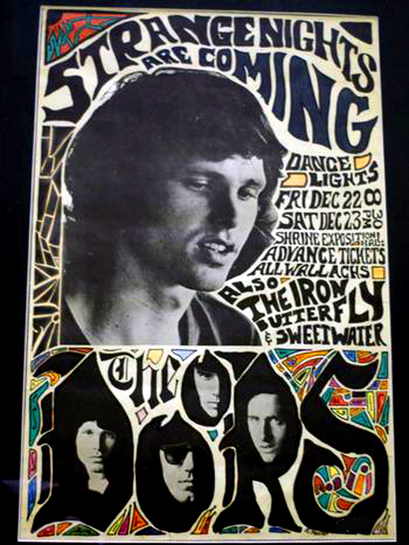

In 1965 the County reluctantly acceded to club-owners' and record companies' pleas and created a tiered licensing system that allowed 18-to-21-year-olds inside clubs where alcohol was served, while creating special liquor-less music venues for younger 15-to-18-year-olds. The youth club scene promptly exploded. From the moment the Byrds debuted at Ciro’s on March 26th 1965 — with Bob Dylan joining them on stage — through the demonstrations of November 1966, Sunset Strip nightclubs introduced the Doors, Buffalo Springfield the Mothers of Invention, and so many more.

This legendary Battle of the Strip, 1966–1968, was only the most celebrated episode in the struggle of teenagers of all colours during the 1960s and 1970s to create their own realm of freedom and carnivalesque sociality within the Southern California night. There were other memorable contests with business and police over Griffith Park 'love-ins', beach parties, interracial concerts, counter-cultural neighbourhoods (like Venice Beach), 'head' shopping districts (like L.A.'s Haight-Ashbury on Fairfax), cruising strips (Whittier, Hollywood, and Van Nuys boulevards), street-racing locales, and the myriad local hangouts where kids quietly or brazenly defied parents, police, and curfews.

THE HIPPIE RIOTS:

Riot on Sunset Strip - "For What It's Worth"

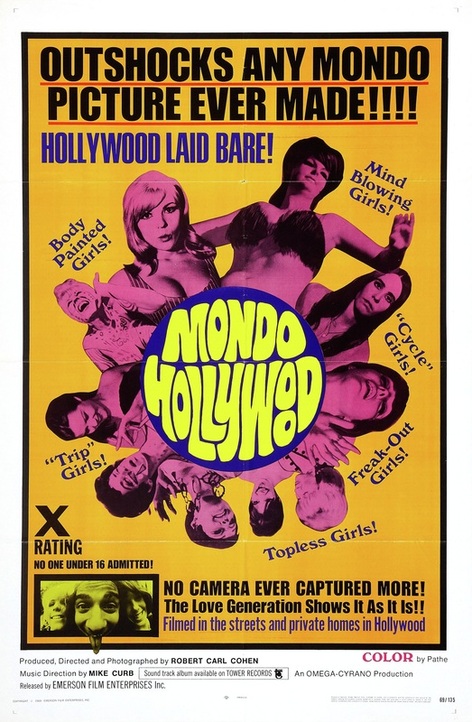

The Sunset Strip curfew riots, also known as the "hippie riots," were a series of clashes that took place between police and young people on the Sunset Strip in Hollywood, California, beginning in the mid-1960s and continuing through the early 1970s. “Riot on the Sunset Strip” is a masterwork of the teen exploitation genre. Released in 1967, the film was made within six weeks. Imagine what it must have been like to be hanging out in Los Angeles - the Sunset Strip during the mid 1960's. Forget about the movie stars, the glitz and glamour of Hollywood – L.A. was a hot bed for Pop music, art, and culture. The scene appeared in an almost over night fashion. The landing of "The Beatles", "The Rolling Stones" and the British Invasion certainly made all of this a reality. But as quickly as it appeared it soon vanished with the riots of 1966 and the gravitating of the scene to San Francisco and the "Summer of Love".

One such riot in the summer of 1966 provided the basis for the teen exploitation film, Riot on Sunset Strip — as well as for the Buffalo Springfield song, "For What It's Worth", which is often mistakenly labelled an antiwar protest song, "Plastic People" by Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention from their second album Absolutely Free, and The Monkees song "Daily Nightly", written by Michael Nesmith, from their fourth album Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd.

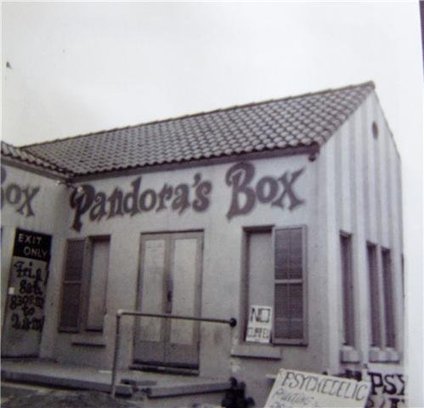

Gangsters, nightclubs and rock 'n' roll make up much of the Sunset Strip's colorful history -- along with a little-remembered tussle in 1966 that became known as "the Sunset Strip riots." The melee erupted as young rock fans were protesting efforts to enforce a 10 p.m. curfew and to close nightclubs that catered to them -- including Pandora's Box, at the corner of Sunset and Crescent Heights boulevards.

The confrontation with police also inspired musician Stephen Stills to write "For What It's Worth," released two months later by Stills and the band he was in, Buffalo Springfield. "Riot is a ridiculous name," he said in an interview. "It was a funeral for Pandora's Box. But it looked like a revolution." The club, painted purple and gold, was perched on a triangular traffic island in the middle of the Strip. It drew a crowd of mostly clean-cut teenagers and twentysomethings wearing pullover sweaters and miniskirts. Ensuing traffic jams annoyed residents and business owners, who pressured the city and county to get rid of the kids, the clubs and the congestion. It's unclear from Times files whether Pandora's Box or other clubs had been closed by the time the protests began. But young rock fans interpreted efforts to enforce curfew and loitering laws as an infringement on their civil rights.

On Nov. 12, 1966, fliers were distributed along the Strip inviting people to demonstrate. Hours before the protest, "One of L.A's rock 'n' roll radio stations made an announcement that there would be a rally at Pandora's Box and cautioned people to tread carefully," wrote Domenic Priore, author of the 2007 book "Riot on Sunset Strip: Rock 'n' Roll's Last Stand in Hollywood." As many as 1,000 people turned out, along with such celebrities as Jack Nicholson and Peter Fonda. "[Nicholson] just showed up to see what was happening," said lifelong Sunset Strip denizen and Hollywood historian Marc Wanamaker. Wanamaker played drums in a band called Mike and the Mad Men, which sometimes performed at Pandora's Box, and was there that night as an observer.

"Everyone called them hippies just because some had long hair," Wanamaker said. "But they weren't the flower-power types from San Francisco, just rock 'n' roll fans, mostly students." The event began peacefully. Protesters sat on the Strip blocking traffic, holding hands and singing. Trouble began when a car full of off-duty Marines got into a fender-bender. The Marines got out of their car and at least one punched the driver of the other car, The Times reported. Fighting spread. Police and sheriffs' deputies closed off part of the Strip and ordered everyone to leave, but some protesters ran amok.

They rocked a city bus until passengers and the driver got out. Then they knocked out the windows, dented the roof with an uprooted street sign and let the air out of the tires. One youth tried unsuccessfully to drop lighted matches into the fuel tank, The Times reported. He was booked for attempted arson. Protesters hurled rocks and bottles and smashed storefront windows and car windshields. Fonda, son of actor Henry Fonda, was handcuffed. But when he said he was merely filming the melee, he was released without charges. The unrest continued the next night and off and on throughout November and December. Some clubs shut down within weeks. "These kids weren't looking for trouble; they were simply going out to see their favorite bands and hang out with friends," Priore wrote.

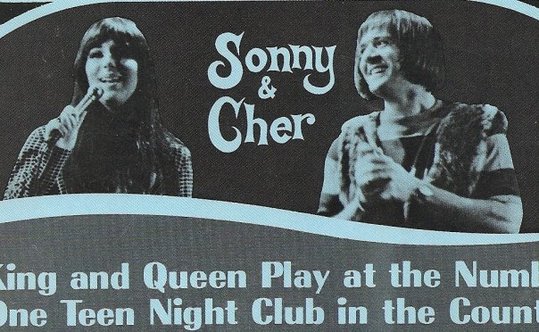

Demonstrators carried signs that read, "We're Your Children! Don't Destroy Us" and "Ban the Billyclub." Mayor Sam Yorty showed up and invited the protesters to City Hall. Los Angeles County Supervisor Ernest Debs called the youths "misguided hoodlums." Sonny and Cher, who got their start on the Strip as Caesar and Cleo, made an appearance in front of Pandora's Box in December. The ensuing publicity got them kicked off the Rose Parade float they were supposed to ride two weeks later. The float sponsor, the City of Monterey Park, figured this was not the image it wanted to show the world. "I admit at first we were somewhat hurt, shocked and a little upset," Sonny Bono said at a news conference after the duo was bumped. "They never even gave us the courtesy of notifying us personally. I heard it on the news."

Bono denied being part of the protest. "[The demonstrators] saw I was there and I told them to be peaceful, that's all," he said. On Christmas Day, Pandora's Box reopened for one night only, according to Priore. There, Stills first publicly performed "For What It's Worth." The Los Angeles City Council condemned Pandora's Box, claiming that it had to be demolished to realign the streets. On Aug. 3, 1967, a wrecking ball turned Pandora's into rubble. "Hippies Pout, Politicians Cheer," The Times reported. No sign of the triangle occupied by Pandora's remains today; it was eliminated by the street rerouting. As for Stills' song, many fans saw it as an antiwar anthem, but he says that was only part of the equation. "It was really four different things intertwined, including the war and the absurdity of what was happening on the Strip," he said in the interview. "But I knew I had to skedaddle and headed back to Topanga, where I wrote my song in about 15 minutes. For me, there was no riot. It was basically a cop dance." http://articles.latimes.com/2007/aug/05/local/me-then5/2

1967 riots on the Strip; the culminating protest in 1968. So what follows is an alloy of research and memory. It is also the first, small installment in a projected history of L.A.'s countercultures and protestors, tentatively titled Setting the Night on Fire.

A MOMENT IN ROCK-AND-ROLL DREAMTIME: Saturday night on Sunset Strip in early December 1967. Along that famed twelve blocks of unincorporated Los Angeles County between Hollywood and Beverly Hills, the neon firmament blazes new names like the Byrds, the Doors, Sonny and Cher, the Mamas and the Papas, and Buffalo Springfield. But the real spectacle is out on the street: 2,000 demonstrators peacefully snaking their way west along Sunset into the county Strip then circling back to their starting point at Pandora's Box Coffeehouse (8180 Sunset) just inside the Los Angeles city limits. On one side of the boundary are several hundred riot-helmeted sheriff's deputies; on the other side, an equal number of Los Angeles police, fidgeting nervously with their nightsticks as if they were confronting angry strikers or an unruly mob instead of friendly 15-year-olds with long hair and acne.

The demonstrators — relentlessly caricatured as 'Striplings', 'teeny boppers', and even 'hoodlums' by hostile cops and their allies in the daily press — are a cross-section of white teenage Southern California. Movie brats from the gilded hills above the Strip mingle with autoworkers' daughters from Van Nuys and truck drivers' sons from Pomona. There are some college students and a few uncomfortable crew-cut servicemen, but most are high-school age, 15 to 18, and, thus, technically liable to arrest after 10 p.m. when dual county and city juvenile curfews take effect. Kids carry hand-lettered signs that read "Stop Blue Fascism!," "Abolish the Curfew," and "Free the Strip."

The demonstration has been called (but scarcely organized) by RAMCON (the Right of Assembly and Movement Committee), headquartered in the Fifth Estate Coffeehouse (8226 Sunset). The coffee house's manager, Al Mitchell, acts as the adult spokesman for the high-school students and teenage runaways who cluster around the Fifth Estate and Pandora's Box, a block away. This is the fifth in a series of weekend demonstrations — perhaps more accurately 'happenings' — that have protested a year-long campaign by sheriffs and police to clear the Strip of 'loitering' teenagers. In response to complaints from local restaurateurs and landowners, the cops trawl nightly after the early curfew, searching for under-18s. They target primarily the longhaired kids in beads, granny glasses, and tie-dyed shirts.

It became the custom to humiliate curfew-violaters with insults and obscene jokes, pull their long hair, brace them against squad cars, and even choke them with billy clubs, before hauling them down to the West Hollywood Sheriffs or Hollywood Police stations where they are held until their angry parents pick them up. This evening (10 December), however, has so far passed off peacefully, with more smiles exchanged than insults or blows. The high point was the appearance of Sonny and Cher, dressed like high-fashion Inuit in huge fleece parkas, waving support to adoring kids. (Later, after photographs have appeared on front pages across the world, the city of Monterey Park will ban Sonny and Cher from their Rose Parade float for this gesture of solidarity with "rioting teenyboppers.")

The Strip grew and reinvented itself, building on its own mythic aura, decade after decade, from the supper clubs of the '40s to the nightclubs of the '50s to the rock clubs of the '60s. The purest metaphor of L.A., it was a mile of sex and self-invention and rampaging capitalism.

SUNSET STRIP AS MEMORY LANE

By S.L. Duff (1988 - Music Connection) During the course of banging out club data, issue 'pon issue, I have had the opportunity to come in contact with some pretty interesting characters. Among my favorites is Coconut Teaszer booker Len Fagan. Oftentimes, when I call him to get news about the Teaszer, or he calls me with something he's genuinely excited about (y'see, Len is one of the few bookers to go out of his way to make my job a little easier), we end up shootin' the proverbial shit about this and that. Local bands, the club scene, music in general---all come into our conversation.

After rapping with him for a few months, I discovered that Len is no Johnny-come-lately to the L.A. club scene; in fact, his experiences on the ever-changing circuit date back to the sixties, when Fagan was a rabid rock fan and an inspiring drummer who logged time in several locally prominent bands. I found his memory for details, names, and incidents to be impeccable, and in most cases better than my recollection of last week. Len also remembers the geographical layout of the late sixties/early seventies club scene, so I asked him what he thought of hopping in a vehicle "cruisin' Sunset" with yours truly, my trusty Panasonic interview recorder, and the Club Data staff driver, letting his recollections roll onto tape as we drove by the old haunts. He loved the idea, and we finally got around to taking the ride on July 16th. The following are some of the highlights of our trip, and though a lot of Len's recollections lie on the cutting floor due to space limitations, this should nonetheless give you some idea of the excitement of those times.

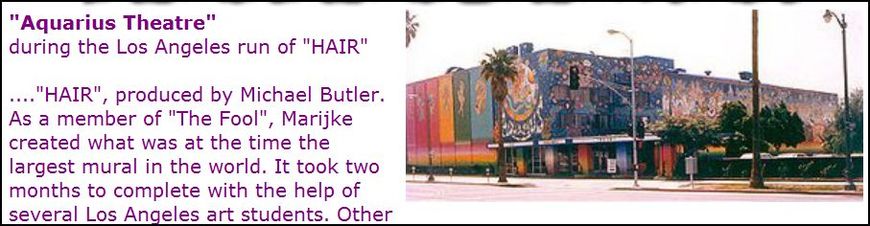

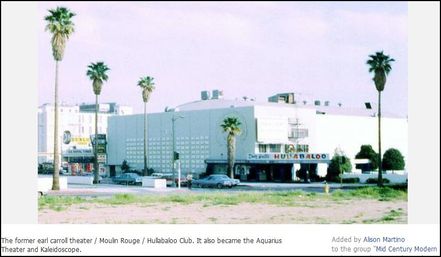

This right here (the Aquarius Theater) was originally the Hullabaloo Club and before that in the 50s, The Moulin Rouge. The hip thing about it was, you could be 15-and-a-half and get in. They'd have everything from lame bands like the Lollipop Shop right up through The Doors. Love used to play here, then they'd play another concert in the Valley the same night. After the Hullabaloo, it changed to the Aquarius Theater. New owners took it over and it became a much hipper place; their posters were round instead of square. When it was the Hullabaloo, on weekends after hours from 1:00 am until sunrise, they'd have new bands get up. You wouldn't get paid, but they'd have a marathon of bands get up, and it was a big deal to get on that show. The Allman Brothers played there when they were the Hourglass.|

(We pull up in front of the current Gaslight.) This, for me, is where it all started. The first place I ever came to myself---and I was living in the Valley at the time---was right here to see Love. It was the summer of '65. I couldn't even get in the club---I used to sit here (on the sidewalk) and listen. Love would play the whole night, and it was completely packed. A few years later, the Iron Butterfly moved in and slept in this room (pointing upstairs over the entrance). They moved up here from San Diego, auditioned, and the club loved 'em and let 'em live in the room upstairs. They played here for months and would pack this place. It was called Bido Lido's back then. I saw the Seeds here, when the first album came out, before "Pushin' Too Hard" was a hit. The Doors played here, so did Spirit. ......I could go on and on. Look how tiny it is! A band's gig here would usually be for a week straight, and if you were incredible, they'd hold you over.

I was in a group called the Rainmakers; we had a week-long gig here, and after the second or third night, our guitar player got sick and couldn't do it. I had met Vincent Furnier outside the club here, and he was a real nice guy. At the last minute, I called up Vince, and his band the Nazz filled in for us. (Furnier and the Nazz would both later change their names to Alice Cooper.) The big break for them was, they met the booker of the Cheetah Club down in Venice, who fell in love with them, and that's where they took up residency, and then they met (manager) Shep Gordon. Bido Lido's went out of business around the end of '67, early '68.

The club we're coming to now was called the Brave New World. Bido Lido's and Brave New World were the smaller East Hollywood clubs where the bands would kinda start out. We would usually park at one of the clubs, and on any given night, walk between one and the next. The Brave New World was owned by a guy named Alan as I remember. Alan was also in the ......I don't know how to say it.....the "X-rated girl" industry. He had something to do with naked women----remember, I'm young at the time! The club was a members only club, so to speak---that's how they got around some kind of licensing trip. If they knew you weren't a cop, they'd let you in. This is where Love first played---probably late '64---right up there at 1644 and 1642 Cherokee. The Stones were in town recording at RCA, and they went here to check out a group called the Bees---that was a big night. The Mothers played here before they were called the Mothers of Invention; if I remember, they spelled the name "Muthers." Instead of a marquee, they had a flag on a flagpole with the band's name.

We're now in front of the Lingerie, which I first remember being the Red Velvet. They had a lot of black and soul groups. The Knickerbockers were the band that came out of here. This was a place that had your short-haired people, your lamer crowd.

Down there, at Santa Monica and Highland, was a club that not many people are goin' to remember; it was in a big old warehouse. It was a gay club, mainly for lesbians, and a lot of the bigger bands would take gigs here, right next to the Bekins warehouse. The gig would start around 11 or 12 at night, and we'd take those gigs, 'cause they paid well. The Knack (a sixties teenybop band signed to a singles deal with---surprise---Capitol) and the Sons of Adam, who were a monster band, used to play there. Don't even remember the name of the place. They finally shut them down and they moved into the Valley on Ventura Boulevard.

Here, at 7563 Sunset, was Ooh Poo Pah Do's, which had live music; that was in '72. And then Rodney (Bingenheimer) took it over and made it a disco, with English beer and English records. That was '73 or '74, and it was big for a couple of years.

Here, between Stanley and Curson, was a big club called The Experience. They had food here and ice-cream. This club was famous as a jam hangout---musicians who were in town playing bigger concerts elsewhere would come here after their shows or on the nights they were off to jam. I've been hoping to make the Teaszer conducive to impromptu jams, but it seems musicians today just aren't into jamming. A shame. Hendrix jammed here all the time. There were always famous celebrities in the audience. There was a big picture of Hendrix (on the exterior front wall of the club), and his mouth was the front door---you'd walk in through his mouth!

The big summer for The Experience was '69; it was probably here for a year-and-a-half, two years, maybe. I remember jamming here with some of the Quicksilver Messenger Service. The Blues Magoos played here on their way down; Alice Cooper played here on their way up---got booed off the stage.

(Sitting in the parking lot of the Teaszer at Crescent Heights.) The hippies hangout was right around here---it started from here down to Gazzarri’s. Pandora's Box was right where that middle island was (in the middle of the intersection of Crescent Heights and Sunset). That wasn't a real prestigious place to play. It was right on the beginning of the Strip, it was a purple building, and it was right there in the middle---a pretty weird location. You could be underage and still get in there. To be honest with you, I didn't hang out there at all---I may have been in that club once. There was something about it that, in my mind, wasn't hip.

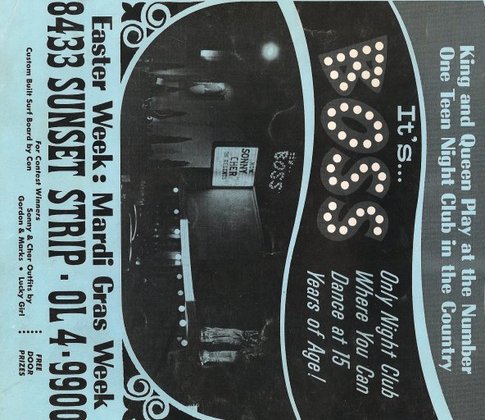

We're at the Comedy Store now, which was first called Ciro's. The Byrds used to play here---this is where they really took off. Bob Dylan came in here after hearing about the Byrds playing his material electrically and gave his endorsement to them, which was a big boost to them making it. Before that, Ciro's was a big hangout for Bogie and all that in the Forties. They later changed the name from Ciro's to It's Boss. Ciro's was over 21; at It's Boss, you could be fifteen-and-a-half. Ciro's was definitely a big, big prestige club. It was open at least to '73 '74, but it was mainly a force in the late Sixties. (As a cop pulls up to give out parking tickets, we quietly pull away.)

Speaking of cops, back in '64, '65, '66, when we used to drive down the street or the Strip, I used to smoke non-filter cigarettes. You had to be careful to have the brand on your mouthside; the cops were so lame that if they caught you with a cigarette with no filter and no name on it, they assumes you were smoking pot. This was when acid was still legal, by the way.

One such riot in the summer of 1966 provided the basis for the teen exploitation film, Riot on Sunset Strip — as well as for the Buffalo Springfield song, "For What It's Worth", which is often mistakenly labelled an antiwar protest song, "Plastic People" by Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention from their second album Absolutely Free, and The Monkees song "Daily Nightly", written by Michael Nesmith, from their fourth album Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd.

Gangsters, nightclubs and rock 'n' roll make up much of the Sunset Strip's colorful history -- along with a little-remembered tussle in 1966 that became known as "the Sunset Strip riots." The melee erupted as young rock fans were protesting efforts to enforce a 10 p.m. curfew and to close nightclubs that catered to them -- including Pandora's Box, at the corner of Sunset and Crescent Heights boulevards.

The confrontation with police also inspired musician Stephen Stills to write "For What It's Worth," released two months later by Stills and the band he was in, Buffalo Springfield. "Riot is a ridiculous name," he said in an interview. "It was a funeral for Pandora's Box. But it looked like a revolution." The club, painted purple and gold, was perched on a triangular traffic island in the middle of the Strip. It drew a crowd of mostly clean-cut teenagers and twentysomethings wearing pullover sweaters and miniskirts. Ensuing traffic jams annoyed residents and business owners, who pressured the city and county to get rid of the kids, the clubs and the congestion. It's unclear from Times files whether Pandora's Box or other clubs had been closed by the time the protests began. But young rock fans interpreted efforts to enforce curfew and loitering laws as an infringement on their civil rights.

On Nov. 12, 1966, fliers were distributed along the Strip inviting people to demonstrate. Hours before the protest, "One of L.A's rock 'n' roll radio stations made an announcement that there would be a rally at Pandora's Box and cautioned people to tread carefully," wrote Domenic Priore, author of the 2007 book "Riot on Sunset Strip: Rock 'n' Roll's Last Stand in Hollywood." As many as 1,000 people turned out, along with such celebrities as Jack Nicholson and Peter Fonda. "[Nicholson] just showed up to see what was happening," said lifelong Sunset Strip denizen and Hollywood historian Marc Wanamaker. Wanamaker played drums in a band called Mike and the Mad Men, which sometimes performed at Pandora's Box, and was there that night as an observer.

"Everyone called them hippies just because some had long hair," Wanamaker said. "But they weren't the flower-power types from San Francisco, just rock 'n' roll fans, mostly students." The event began peacefully. Protesters sat on the Strip blocking traffic, holding hands and singing. Trouble began when a car full of off-duty Marines got into a fender-bender. The Marines got out of their car and at least one punched the driver of the other car, The Times reported. Fighting spread. Police and sheriffs' deputies closed off part of the Strip and ordered everyone to leave, but some protesters ran amok.

They rocked a city bus until passengers and the driver got out. Then they knocked out the windows, dented the roof with an uprooted street sign and let the air out of the tires. One youth tried unsuccessfully to drop lighted matches into the fuel tank, The Times reported. He was booked for attempted arson. Protesters hurled rocks and bottles and smashed storefront windows and car windshields. Fonda, son of actor Henry Fonda, was handcuffed. But when he said he was merely filming the melee, he was released without charges. The unrest continued the next night and off and on throughout November and December. Some clubs shut down within weeks. "These kids weren't looking for trouble; they were simply going out to see their favorite bands and hang out with friends," Priore wrote.

Demonstrators carried signs that read, "We're Your Children! Don't Destroy Us" and "Ban the Billyclub." Mayor Sam Yorty showed up and invited the protesters to City Hall. Los Angeles County Supervisor Ernest Debs called the youths "misguided hoodlums." Sonny and Cher, who got their start on the Strip as Caesar and Cleo, made an appearance in front of Pandora's Box in December. The ensuing publicity got them kicked off the Rose Parade float they were supposed to ride two weeks later. The float sponsor, the City of Monterey Park, figured this was not the image it wanted to show the world. "I admit at first we were somewhat hurt, shocked and a little upset," Sonny Bono said at a news conference after the duo was bumped. "They never even gave us the courtesy of notifying us personally. I heard it on the news."

Bono denied being part of the protest. "[The demonstrators] saw I was there and I told them to be peaceful, that's all," he said. On Christmas Day, Pandora's Box reopened for one night only, according to Priore. There, Stills first publicly performed "For What It's Worth." The Los Angeles City Council condemned Pandora's Box, claiming that it had to be demolished to realign the streets. On Aug. 3, 1967, a wrecking ball turned Pandora's into rubble. "Hippies Pout, Politicians Cheer," The Times reported. No sign of the triangle occupied by Pandora's remains today; it was eliminated by the street rerouting. As for Stills' song, many fans saw it as an antiwar anthem, but he says that was only part of the equation. "It was really four different things intertwined, including the war and the absurdity of what was happening on the Strip," he said in the interview. "But I knew I had to skedaddle and headed back to Topanga, where I wrote my song in about 15 minutes. For me, there was no riot. It was basically a cop dance." http://articles.latimes.com/2007/aug/05/local/me-then5/2

1967 riots on the Strip; the culminating protest in 1968. So what follows is an alloy of research and memory. It is also the first, small installment in a projected history of L.A.'s countercultures and protestors, tentatively titled Setting the Night on Fire.

A MOMENT IN ROCK-AND-ROLL DREAMTIME: Saturday night on Sunset Strip in early December 1967. Along that famed twelve blocks of unincorporated Los Angeles County between Hollywood and Beverly Hills, the neon firmament blazes new names like the Byrds, the Doors, Sonny and Cher, the Mamas and the Papas, and Buffalo Springfield. But the real spectacle is out on the street: 2,000 demonstrators peacefully snaking their way west along Sunset into the county Strip then circling back to their starting point at Pandora's Box Coffeehouse (8180 Sunset) just inside the Los Angeles city limits. On one side of the boundary are several hundred riot-helmeted sheriff's deputies; on the other side, an equal number of Los Angeles police, fidgeting nervously with their nightsticks as if they were confronting angry strikers or an unruly mob instead of friendly 15-year-olds with long hair and acne.

The demonstrators — relentlessly caricatured as 'Striplings', 'teeny boppers', and even 'hoodlums' by hostile cops and their allies in the daily press — are a cross-section of white teenage Southern California. Movie brats from the gilded hills above the Strip mingle with autoworkers' daughters from Van Nuys and truck drivers' sons from Pomona. There are some college students and a few uncomfortable crew-cut servicemen, but most are high-school age, 15 to 18, and, thus, technically liable to arrest after 10 p.m. when dual county and city juvenile curfews take effect. Kids carry hand-lettered signs that read "Stop Blue Fascism!," "Abolish the Curfew," and "Free the Strip."

The demonstration has been called (but scarcely organized) by RAMCON (the Right of Assembly and Movement Committee), headquartered in the Fifth Estate Coffeehouse (8226 Sunset). The coffee house's manager, Al Mitchell, acts as the adult spokesman for the high-school students and teenage runaways who cluster around the Fifth Estate and Pandora's Box, a block away. This is the fifth in a series of weekend demonstrations — perhaps more accurately 'happenings' — that have protested a year-long campaign by sheriffs and police to clear the Strip of 'loitering' teenagers. In response to complaints from local restaurateurs and landowners, the cops trawl nightly after the early curfew, searching for under-18s. They target primarily the longhaired kids in beads, granny glasses, and tie-dyed shirts.

It became the custom to humiliate curfew-violaters with insults and obscene jokes, pull their long hair, brace them against squad cars, and even choke them with billy clubs, before hauling them down to the West Hollywood Sheriffs or Hollywood Police stations where they are held until their angry parents pick them up. This evening (10 December), however, has so far passed off peacefully, with more smiles exchanged than insults or blows. The high point was the appearance of Sonny and Cher, dressed like high-fashion Inuit in huge fleece parkas, waving support to adoring kids. (Later, after photographs have appeared on front pages across the world, the city of Monterey Park will ban Sonny and Cher from their Rose Parade float for this gesture of solidarity with "rioting teenyboppers.")

The Strip grew and reinvented itself, building on its own mythic aura, decade after decade, from the supper clubs of the '40s to the nightclubs of the '50s to the rock clubs of the '60s. The purest metaphor of L.A., it was a mile of sex and self-invention and rampaging capitalism.

SUNSET STRIP AS MEMORY LANE

By S.L. Duff (1988 - Music Connection) During the course of banging out club data, issue 'pon issue, I have had the opportunity to come in contact with some pretty interesting characters. Among my favorites is Coconut Teaszer booker Len Fagan. Oftentimes, when I call him to get news about the Teaszer, or he calls me with something he's genuinely excited about (y'see, Len is one of the few bookers to go out of his way to make my job a little easier), we end up shootin' the proverbial shit about this and that. Local bands, the club scene, music in general---all come into our conversation.

After rapping with him for a few months, I discovered that Len is no Johnny-come-lately to the L.A. club scene; in fact, his experiences on the ever-changing circuit date back to the sixties, when Fagan was a rabid rock fan and an inspiring drummer who logged time in several locally prominent bands. I found his memory for details, names, and incidents to be impeccable, and in most cases better than my recollection of last week. Len also remembers the geographical layout of the late sixties/early seventies club scene, so I asked him what he thought of hopping in a vehicle "cruisin' Sunset" with yours truly, my trusty Panasonic interview recorder, and the Club Data staff driver, letting his recollections roll onto tape as we drove by the old haunts. He loved the idea, and we finally got around to taking the ride on July 16th. The following are some of the highlights of our trip, and though a lot of Len's recollections lie on the cutting floor due to space limitations, this should nonetheless give you some idea of the excitement of those times.

This right here (the Aquarius Theater) was originally the Hullabaloo Club and before that in the 50s, The Moulin Rouge. The hip thing about it was, you could be 15-and-a-half and get in. They'd have everything from lame bands like the Lollipop Shop right up through The Doors. Love used to play here, then they'd play another concert in the Valley the same night. After the Hullabaloo, it changed to the Aquarius Theater. New owners took it over and it became a much hipper place; their posters were round instead of square. When it was the Hullabaloo, on weekends after hours from 1:00 am until sunrise, they'd have new bands get up. You wouldn't get paid, but they'd have a marathon of bands get up, and it was a big deal to get on that show. The Allman Brothers played there when they were the Hourglass.|

(We pull up in front of the current Gaslight.) This, for me, is where it all started. The first place I ever came to myself---and I was living in the Valley at the time---was right here to see Love. It was the summer of '65. I couldn't even get in the club---I used to sit here (on the sidewalk) and listen. Love would play the whole night, and it was completely packed. A few years later, the Iron Butterfly moved in and slept in this room (pointing upstairs over the entrance). They moved up here from San Diego, auditioned, and the club loved 'em and let 'em live in the room upstairs. They played here for months and would pack this place. It was called Bido Lido's back then. I saw the Seeds here, when the first album came out, before "Pushin' Too Hard" was a hit. The Doors played here, so did Spirit. ......I could go on and on. Look how tiny it is! A band's gig here would usually be for a week straight, and if you were incredible, they'd hold you over.

I was in a group called the Rainmakers; we had a week-long gig here, and after the second or third night, our guitar player got sick and couldn't do it. I had met Vincent Furnier outside the club here, and he was a real nice guy. At the last minute, I called up Vince, and his band the Nazz filled in for us. (Furnier and the Nazz would both later change their names to Alice Cooper.) The big break for them was, they met the booker of the Cheetah Club down in Venice, who fell in love with them, and that's where they took up residency, and then they met (manager) Shep Gordon. Bido Lido's went out of business around the end of '67, early '68.

The club we're coming to now was called the Brave New World. Bido Lido's and Brave New World were the smaller East Hollywood clubs where the bands would kinda start out. We would usually park at one of the clubs, and on any given night, walk between one and the next. The Brave New World was owned by a guy named Alan as I remember. Alan was also in the ......I don't know how to say it.....the "X-rated girl" industry. He had something to do with naked women----remember, I'm young at the time! The club was a members only club, so to speak---that's how they got around some kind of licensing trip. If they knew you weren't a cop, they'd let you in. This is where Love first played---probably late '64---right up there at 1644 and 1642 Cherokee. The Stones were in town recording at RCA, and they went here to check out a group called the Bees---that was a big night. The Mothers played here before they were called the Mothers of Invention; if I remember, they spelled the name "Muthers." Instead of a marquee, they had a flag on a flagpole with the band's name.

We're now in front of the Lingerie, which I first remember being the Red Velvet. They had a lot of black and soul groups. The Knickerbockers were the band that came out of here. This was a place that had your short-haired people, your lamer crowd.

Down there, at Santa Monica and Highland, was a club that not many people are goin' to remember; it was in a big old warehouse. It was a gay club, mainly for lesbians, and a lot of the bigger bands would take gigs here, right next to the Bekins warehouse. The gig would start around 11 or 12 at night, and we'd take those gigs, 'cause they paid well. The Knack (a sixties teenybop band signed to a singles deal with---surprise---Capitol) and the Sons of Adam, who were a monster band, used to play there. Don't even remember the name of the place. They finally shut them down and they moved into the Valley on Ventura Boulevard.

Here, at 7563 Sunset, was Ooh Poo Pah Do's, which had live music; that was in '72. And then Rodney (Bingenheimer) took it over and made it a disco, with English beer and English records. That was '73 or '74, and it was big for a couple of years.

Here, between Stanley and Curson, was a big club called The Experience. They had food here and ice-cream. This club was famous as a jam hangout---musicians who were in town playing bigger concerts elsewhere would come here after their shows or on the nights they were off to jam. I've been hoping to make the Teaszer conducive to impromptu jams, but it seems musicians today just aren't into jamming. A shame. Hendrix jammed here all the time. There were always famous celebrities in the audience. There was a big picture of Hendrix (on the exterior front wall of the club), and his mouth was the front door---you'd walk in through his mouth!

The big summer for The Experience was '69; it was probably here for a year-and-a-half, two years, maybe. I remember jamming here with some of the Quicksilver Messenger Service. The Blues Magoos played here on their way down; Alice Cooper played here on their way up---got booed off the stage.

(Sitting in the parking lot of the Teaszer at Crescent Heights.) The hippies hangout was right around here---it started from here down to Gazzarri’s. Pandora's Box was right where that middle island was (in the middle of the intersection of Crescent Heights and Sunset). That wasn't a real prestigious place to play. It was right on the beginning of the Strip, it was a purple building, and it was right there in the middle---a pretty weird location. You could be underage and still get in there. To be honest with you, I didn't hang out there at all---I may have been in that club once. There was something about it that, in my mind, wasn't hip.

We're at the Comedy Store now, which was first called Ciro's. The Byrds used to play here---this is where they really took off. Bob Dylan came in here after hearing about the Byrds playing his material electrically and gave his endorsement to them, which was a big boost to them making it. Before that, Ciro's was a big hangout for Bogie and all that in the Forties. They later changed the name from Ciro's to It's Boss. Ciro's was over 21; at It's Boss, you could be fifteen-and-a-half. Ciro's was definitely a big, big prestige club. It was open at least to '73 '74, but it was mainly a force in the late Sixties. (As a cop pulls up to give out parking tickets, we quietly pull away.)

Speaking of cops, back in '64, '65, '66, when we used to drive down the street or the Strip, I used to smoke non-filter cigarettes. You had to be careful to have the brand on your mouthside; the cops were so lame that if they caught you with a cigarette with no filter and no name on it, they assumes you were smoking pot. This was when acid was still legal, by the way.

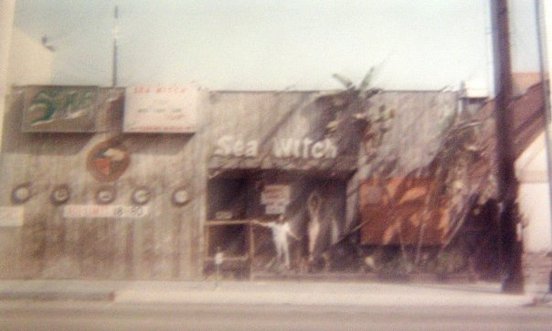

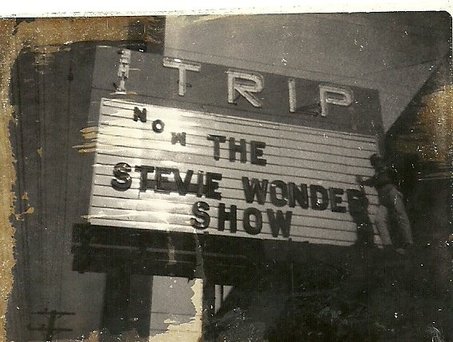

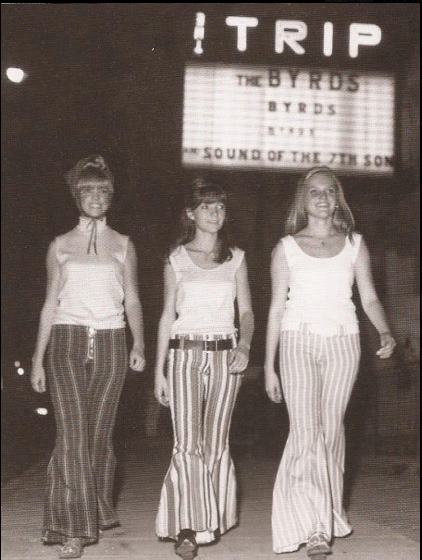

Right over here, at 8516, there was a tiny club called the Sea Witch. The capacity in that club was maybe 60 people. The thing about the Sea Witch that was neat was it was designed all out of raw wood and was supposed to look like a ship. That was another place on the Strip to play---always crowded. That was about '64 to '67. There's the Playboy Building. On the far end of the Playboy Building there used to be a marquee, and that was a club called the Trip. I remember driving by and seeing on the marquee---I'll never forget this---"Andy Warhol's Exploding Plastic Inevitable with the Velvet Underground and Nico"---on the goddamn marquee. Now what the heck is that, right? I had no idea.

The white banana album had just come out, and the Velvet Underground moved into town, played there for at least a week or so, and rented a big castle up here in the hills, and they were very, very strange people. What was I, 18 at the time? To me it was scary. The Lovin' Spoonful played at the Trip when they were at their biggest. The Byrds used to play at the Trip. That was '65 through '67, I think, when the Trip was at its biggest. Over 21 club. The Central used to be Filthy McNasty's, where it was kind of a lame trip. It was here as far back as I can remember.

We are now at Clark and Sunset, the world-famous friggin' Whisky A-Go-Go. This is it. When I first came here, the building was red, and there were little awnings up there all over the windows, and it looked like a French discotheque. Mario used to stand there, forever---always a fixture. The first time I was in the Whisky, I was hanging out right here; it was raining. It was either Moby Grape or Janis Joplin---somebody like that was playing inside---and I didn't have the money, and I was huddled here listening. And Mario was over there and he yelled at me, "What's the matter, don't you have any money?" I go no. He goes "Get inside." That was Mario for ya. Great guy. People say Bill Gazzari was the godfather of rock, but I think Mario was the godfather. He watched us all grow up here. I remember nights I'd come here, he'd grab me and say, "You look like shit. What are you on? You haven't eaten in a week!" Drag me over to the bar and say, "Give him a hamburger ---and you sit down and eat it!" The best. Nobody does that---who does that anymore?

Where Duke's is now was a little club called the London Fog. The Doors played here; wasn't open very long. It quickly became an upscale bar called Sneaky Pete's.

Here (at 8923 Sunset) was the Galaxy. They had a flat marquee and an upstairs infamous for sexual promiscuity. A lot of good bands played here. Here, in between Clark and Hilldale, people were openly selling grass and acid. Love, on the Forever Changes album, have a song called, "Between Clark and Hilldale." This one block was the throbbing heart of it all. When I first started coming into town, there was a Gazzarri’s here, and another one down on La Cienega that wasn't quite as hip. This place always had the Gazzarri’s girls, the dancing trip.

The Roxy they opened around '72, '73, and the Rainbow opened around that same time. The Rainbow was supposed to be a place for the business people in the industry to come and take meetings. Because the musicians knew the industry people were going to be here, the musicians would hang out, and because the musicians were here, the groupies would come, and because the groupies were here, the wanna-be musicians would come. It just became a scene and it's never stopped.....

As we left the Strip, Len talked about the Fifth Estate and the Stratford on Sunset, as well as the Beach House and the Cheetah, both out on the Venice Pier. We drove past the Troubadour, an old venue called the Factory, and finally the Starwood, which was PJ's in the Sixties and is now yet another mini-mall. "Everything that you see bands do now, has been done before," Len told me. "Back then, someone would come along with something original. But it really was a different scene back then. You could always find a jam session at a club or some band's communal house---24 hours a day." Ya shoulda been there.

Every rock band in the world was on the Strip, and not just the flash in the pans, either, but the groups everyone knew were going to last forever--bands like Gerry and the Pacemakers, Freddie and the Dreamers, Chad and Jeremy, and Peter and Gordon. (Sonny and Cher, who began playing clubs on the Strip as Caesar and Cleo, hung out there until it got them kicked out of the Rose Parade when their sponsors figured this was not the image they wanted their float to present the world.)

And the clubs! On any night you could find the Turtles harmonizing "Happy Together" at the Tiger's Tail, the Doors getting thrown off the stage at the London Fog, Buffalo Springfield singing that something was happening here inside Gazzarri's. You could knock on the back door at Ciro's and have Roger McGuinn of the Byrds invite you in; and if you had a joint in your purse, the question was, What are you doing later? The Dorsey Girls would start at Beado Lido's, where you could usually find this furry freak named Frank Zappa playing . . . well, what would you call it? . . . noise . . . and then move on to Pandora's Box at Crescent Heights, and then on to the Stratford and the Sea Witch, the Whisky and the Trip; finally ending the grand circuit inside of Ben Frank's for French fries, where the Dorsey Girls stayed until they were kicked out, at which point they'd drive down to the International House of Pancakes and get kicked out of there, and eventually drag themselves into Canter's at 4 in the morning, where they'd wait for the rising sun to scare them back into their little ranch-style dens.

1960-70s:

We are now at Clark and Sunset, the world-famous friggin' Whisky A-Go-Go. This is it. When I first came here, the building was red, and there were little awnings up there all over the windows, and it looked like a French discotheque. Mario used to stand there, forever---always a fixture. The first time I was in the Whisky, I was hanging out right here; it was raining. It was either Moby Grape or Janis Joplin---somebody like that was playing inside---and I didn't have the money, and I was huddled here listening. And Mario was over there and he yelled at me, "What's the matter, don't you have any money?" I go no. He goes "Get inside." That was Mario for ya. Great guy. People say Bill Gazzari was the godfather of rock, but I think Mario was the godfather. He watched us all grow up here. I remember nights I'd come here, he'd grab me and say, "You look like shit. What are you on? You haven't eaten in a week!" Drag me over to the bar and say, "Give him a hamburger ---and you sit down and eat it!" The best. Nobody does that---who does that anymore?

Where Duke's is now was a little club called the London Fog. The Doors played here; wasn't open very long. It quickly became an upscale bar called Sneaky Pete's.

Here (at 8923 Sunset) was the Galaxy. They had a flat marquee and an upstairs infamous for sexual promiscuity. A lot of good bands played here. Here, in between Clark and Hilldale, people were openly selling grass and acid. Love, on the Forever Changes album, have a song called, "Between Clark and Hilldale." This one block was the throbbing heart of it all. When I first started coming into town, there was a Gazzarri’s here, and another one down on La Cienega that wasn't quite as hip. This place always had the Gazzarri’s girls, the dancing trip.

The Roxy they opened around '72, '73, and the Rainbow opened around that same time. The Rainbow was supposed to be a place for the business people in the industry to come and take meetings. Because the musicians knew the industry people were going to be here, the musicians would hang out, and because the musicians were here, the groupies would come, and because the groupies were here, the wanna-be musicians would come. It just became a scene and it's never stopped.....

As we left the Strip, Len talked about the Fifth Estate and the Stratford on Sunset, as well as the Beach House and the Cheetah, both out on the Venice Pier. We drove past the Troubadour, an old venue called the Factory, and finally the Starwood, which was PJ's in the Sixties and is now yet another mini-mall. "Everything that you see bands do now, has been done before," Len told me. "Back then, someone would come along with something original. But it really was a different scene back then. You could always find a jam session at a club or some band's communal house---24 hours a day." Ya shoulda been there.

Every rock band in the world was on the Strip, and not just the flash in the pans, either, but the groups everyone knew were going to last forever--bands like Gerry and the Pacemakers, Freddie and the Dreamers, Chad and Jeremy, and Peter and Gordon. (Sonny and Cher, who began playing clubs on the Strip as Caesar and Cleo, hung out there until it got them kicked out of the Rose Parade when their sponsors figured this was not the image they wanted their float to present the world.)

And the clubs! On any night you could find the Turtles harmonizing "Happy Together" at the Tiger's Tail, the Doors getting thrown off the stage at the London Fog, Buffalo Springfield singing that something was happening here inside Gazzarri's. You could knock on the back door at Ciro's and have Roger McGuinn of the Byrds invite you in; and if you had a joint in your purse, the question was, What are you doing later? The Dorsey Girls would start at Beado Lido's, where you could usually find this furry freak named Frank Zappa playing . . . well, what would you call it? . . . noise . . . and then move on to Pandora's Box at Crescent Heights, and then on to the Stratford and the Sea Witch, the Whisky and the Trip; finally ending the grand circuit inside of Ben Frank's for French fries, where the Dorsey Girls stayed until they were kicked out, at which point they'd drive down to the International House of Pancakes and get kicked out of there, and eventually drag themselves into Canter's at 4 in the morning, where they'd wait for the rising sun to scare them back into their little ranch-style dens.

1960-70s:

- Key Club sits on the site that was once Gazzarri's, a renowned Sunset Strip venue that gave bands like the Doors and Van Halen their starts.

- Whisky A Go-Go was opened in the 1960s by a former Chicago cop named Elmer Valentine. He modeled the discotheque after a club he had seen in Paris, and suspended the 1st female DJ in a glass cage above the dance floor. Go-Go girls were born when he put women in mini-skirts and short white boots in cages around the club. Johnny River's was the live act when it first opened, and Jim Morrison and the Doors became the house band in 1966. The Who, the Kinks, the Byrds, Led Zeppelin, AC/DC, and Jimi Hendrix all also played at the Whisky.